In 2020, Bihar was reeling under the first wave of Covid-19. Unofficially, about 2.5 million migrant workers had returned to their native villages as they had lost their jobs due to the nationwide lockdown. But when the lockdown was lifted after a few months that year, Bihar, an eastern state with a population of 120 million (12 crore), was on the cusp of assembly elections. Bihar was the first state in India where a major election was going to be held after the devastating pandemic.

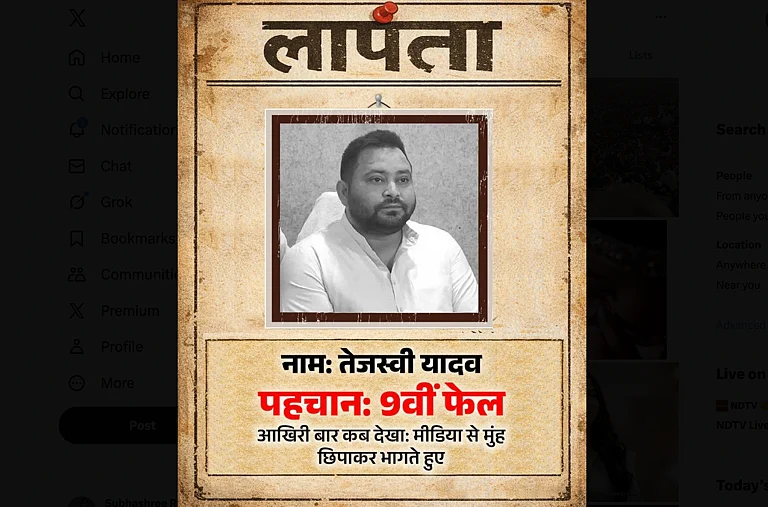

Since, there is a dearth of private factories in Bihar, the first choice or compulsion for the youth is government jobs. So, 33-year-old Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) leader Tejashwi Yadav made ‘jobs’ an election issue. It was perhaps the most significant deviation from the polarisation and counter-polarisation on religion and caste lines, which had been dominating electoral politics for quite some time. Much before the assembly elections, cricketer-turned-politician Yadav had started his campaign, which was centered around job creation. On September 5, 2020, he launched a portal named ‘Berojgari Hatao’ (eliminate unemployment) and launched a toll free number for the registration of unemployed youth.

After three weeks, he claimed 0.94 million unemployed youth had registered themselves in the portal and 1.31 million people had registered themselves by giving missed calls to the toll free number. However, the ‘Berojgari Hatao’ portal is now defunct.

RJD was first to launch its election manifesto. On October 10, 2020, the party released its manifesto and the first point in it was the creation of one million jobs. For the next one and a half months, the promise of one million jobs remained the central issue of his election campaign.

Yadav was the only star campaigner from his party. He held more than 250 election meetings and reiterated the same thing in the public meeting—Hamari Sarkar banne par pehli cabinet mein pehli kalam se Bihar ke 10 lakh yuvaon ko sthai naukri di jayegi (If our government is formed, in the first cabinet meeting itself, 10 lakh youth will be given permanent jobs).

RJD was leading the Mahagathbandhan or the grand alliance, which had the Congress, the Communist Party of India (Marxist), Communist Party of India, Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) Liberation and Hindustani Awam Morcha (HAM).

This was the first time the RJD had made the basic and most important issue of unemployment as an election issue, leaving aside caste and religion.

RJD is known for its Muslim Yadav (MY) winning equation, which together makes for about 30 per cent votes, but Tejashwi did not talk about it at all. Rather, he projected the RJD as a party that did not represent any particular caste or religion. In his election meetings, he described RJD as a party of A to Z—RJD is a party which respects all the castes and gives representation to them.

However, in the distribution of tickets, he succumbed to his caste equation. He not only gave many tickets to his core vote banks, but also tried to accommodate upper castes leaders as well.

RJD fought 144 seats—58 seats were given to yadav leaders; 15 seats to muslims leaders; 23 tickets to OBC (other backward community) leaders; and, about 13 tickets were given to upper castes Rajput, Bhumihar and Brahmin leaders.

Interestingly, the pictures of Lalu Prasad Yadav disappeared from the posters and banners of the party. A party insider says, “In the last 18 years, Laluji’s image was made out to be a leader during whose regime there was alleged Jungle Raj in Bihar. The youth do not know how Laluji’s regime was. They were trapped in the propaganda of Jungle Raj. That’s why RJD decided not to have Laluji’s picture in the election posters.” Tejashwi Yadav’s bet on the unemployment issue was very effective on the ground. In a way, he set the agenda for the election and forced the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to come on its turf.

The BJP always tries to fight elections around religious issues. This is the home turf of the BJP, so it becomes difficult for other parties to take on the saffron party on the basis of religious issues. However, Tejashwi Yadav made unemployment such an important issue in the 2020 assembly elections that even the BJP was forced to talk about unemployment.

BJP released its manifesto 10 days after RJD released its manifesto and promised 19 lakh jobs. Along with this, BJP also promised scooter and laptops to 5,000 meritorious students of class 10th and 12th; launch of Make in Bihar in line with Make in India; colour TVs to Dalits and Mahadalit families, and, providing sarees and dhotis every year to poor families, among others.

Patna-based journalist Deepak Mishra says, “You cannot challenge the BJP on Hindutva. Tejashwi probably realised this, so he did not touch religious issues, but stuck to jobs. Since jobs are a big issue, it struck the right chord.” “Tejashwi downplayed the MY equation as well. That’s how the RJD put the BJP on the backfoot,” says Mishra. The Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), Delhi, in its analysis after the Bihar election results underlined that the strategy to put unemployment at the heart of its campaign did work in its favour.

It further added, “Among voters for whom the job crisis mattered the most, the Mahagathbandhan ended up securing over half the votes and leading the NDA by a massive margin.” RJD won 75 seats and became the single-largest party. It got 23.11 per cent of the votes, which was 4.79 per cent more than the 2015 assembly elections. At the same time, RJD lost five seats as compared to the 2015 assembly elections. The BJP gained 21 seats in this election, but its vote share declined by 4.96 per cent.

Though BJP, under pressure, promised 19 lakh jobs in its manifesto, its party leaders kept trying to capitalise on their core issue of Hindutva in the election campaign. Prime Minister Narendra Modi did not directly mention the Ram Mandir, but indirectly tried to tell the public that BJP had fulfilled the promise of Ram Mandir. BJP leader and UP Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath mentioned Ram Mandir and Article 370 in almost every election speech. He even raised slogans of Jai Shri Ram. On November 2, 2020, while addressing a public meeting in West Champaran, he said, “I have come with the message of Lord Ram from Ayodhya. We did as we said. The work of building Ram temple has started. Now no one will say that BJP did not do what it said.”

Along with this, BJP focused on development issues that largely relied on work done by the Modi government at the centre. In ticket distribution, BJP gave priority to upper castes.

Experts say that in the 2020 Bihar assembly elections, a different thing was seen from the traditional election campaign: it shows that the priorities of the common people have also changed now.

Economist N. K. Chowdhary says, “We clearly saw in that election that the prime focus was on jobs in election rallies, thanks to Tejashwi Yadav. Lalu Yadav ruled Bihar for 15 years invoking social justice. But now only social justice is not going to work, because the priorities of the people have changed.”

Probably, Nitish Kumar was the first to realise this. That’s why he emphasised on social development as well as empowerment, development of infrastructure and empowerment of women. And he was rewarded for that. He continued to get the votes of his own Kurmi caste and secured a large share of women voters.

Although he suffered a heavy loss in the election, it was not because of his election campaign, but because of the Lok Janshakti Party (LJP), which has now split into two factions. One faction is led by Pashupatinath Paras, brother of party founder, the late Ram Vilas Paswan and the other faction is led by Ram Vilas Paswan’s son Chirag Paswan, who has declared himself as Narendra Modi’s Hanuman on several occasions.

The Lok Janshakti Party rebelled against the NDA and fielded its candidates on all the seats JDU was fighting, resulting in a loss of 28 seats.

The most diverse manifesto was of the Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) Liberation. In 12-page manifesto, it included almost all the issues right from health to agriculture, pollution, rights of scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, unemployment, minority welfare and implementation of Sachar Committee’s recommendations. The party, which has a good hold among musahars and other scheduled caste groups won 12 seats which is four times more, when compared to the 2015 assembly elections.

Chaudhary believes that the people’s mindset has changed, so parties will have to choose the issues cautiously. “Lalu Prasad Yadav ran Bihar for 15 years just on the issue of social justice. But now their priority have changed,” Chaudhary says. “So, only sticking to the dharma (religion) or jati (caste) cannot guarantee votes. Along with religion and caste, political parties will have to include development and good governance as well,” he adds.

(Views expressed are personal)

(This appeared in the print as 'Why Manifestos Work')

Umesh Kumar Ray is an independent journalist