The air quality is getting intense, the drums sound like distant thunder, like the infantry rolling in. Fireworks have always punctuated India’s soundscape in recent years, but the feel is suddenly that of an approaching crescendo. After a period of some confusion and doubt, BJP footsoldiers are again out in full martial aspect, swamping real and virtual spaces. “Hindus are anxious,” goes the chanted refrain. Everything is painted as acts of forces inimical to faith, and turned political. The court’s delay over the Ayodhya verdict, the decision to allow women into the Sabarimala shrine, even pollution control. The captains and their lieutenants are hyperactive too, changing the name of cities, dangling private member bills, marshalling truculent troops, talking of termites.

There is nothing random about the stridency; it’s not cacophony, but organised noise. Yes, a clutch of crucial assembly elections are at hand this winter, but this is no ephemeral gust of wind. The BJP’s orchestra conductors seem to be building up a slow fire that will be tended and groomed to full size in time for the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. Make no mistake: the cycle of national politics has entered its final stretch. The timing is no coincidence either; it’s a well-thought-out strategy map. The ratings of Congress president Rahul Gandhi are relatively high, though still nowhere close to the personal popularity of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. BJP leaders may pooh-pooh the Gandhi scion’s persistent attacks on Modi—“desh ka chowkidar chor hai”—but there is a degree of genuine concern.

For one, bad news isn’t in short supply: take Rafale, runaway tycoons, the mess in banks, the sinking rupee, the perennial issues of joblessness, fuel prices and anger on the farms peaking rather than ebbing away, the faceoff with the RBI, and the flameout in the CBI. November 8, the second anniversary of demonetisation, is an apt time to recall this sense of messy governance (see ‘Cash Scrap a Cropper’). The good news, on the other hand, doesn’t make itself too apparent. Social sector benefits can be real and tangible on the ground, and always influence votes substantially—LPG cylinders and roads, for instance, change rural lives—but these roll out far from the public eye. A positive attitude on Article 377 affects only an electorally insignificant minority. For immediate PR advantage, the BJP has to fall back on spectacle and statuary. Still, internally, a quiet optimism reigns.

A Congress protest against alleged corruption in the Rafale deal

How the competing pull of issues affects the electorate’s mood is always a mystery. Take Rafale. One reading is that ordinary voters don’t understand the complexity of defence deals, so it’s irrelevant. But they do know Ambani and Adani, and the idea that ‘Modi sarkar’ has favoured a chosen few corporate biggies isn’t hard to get. (V.P. Singh first demonstrated the electoral utility of such issues with Bofors.) The implosion within the CBI has also come to the doorstep of the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO): things didn’t look pretty, with reports of rival lobbies playing in the background.

Will any of this affect voting patterns? It’s impossible to allocate the contributory effects of single issues, but a cumulative sense can indeed build up. Efforts are on, therefore, to ensure the PM remains sheltered from accusations. “There is an unsaid diktat: come what may, nothing should reflect on Modiji’s chhavi (personal image). That’s where the line is drawn,” a senior BJP leader tells Outlook. The rest can be managed. This includes the disenchantment of the middle class.

“We know the middle class is unhappy with us. They feel we haven’t done enough for them. There’s the fuel prices. And they think we are curbing dissent. They forget it’s the BJP government that helped decriminalise homosexuality and struck down triple talaq. It’s not possible to please the middle class. No government has been able to do so,” he adds. An intrinsic, though unstated, part of the argument is that the party doesn’t really need middle-class votes to get past the winning post.

Those numbers get harvested elsewhere. Away from the public gaze, coloured by heightened emotions as it is, the party’s backroom boys are busy, quietly crunching numbers and formulating strategy. The immediate goal is to go all out to win the five upcoming assembly elections, but the ultimate mission is to ensure the Modi government’s return, and with a victory margin bigger than 2014.

The BJP gives itself credit for the Supreme Court verdict on triple talaq

It’s too early to prophesise on the summer of 2019, but analysis on available figures can throw up plenty surprises (see ‘Modi, Minus 10, Can Still Win’). The BJP had won 282 seats with a vote share of only 31 per cent in 2014. “This time we are working towards a voteshare of 51 per cent and over 300 seats for the BJP,” says a senior BJP leader coordinating backend efforts. “We are quite confident. If we can manage over half the voteshare, we don’t have to worry about the Opposition coming together.” There is no arrogance or bluster in his speech, often seen in his party leaders’ public discourse. Only a quiet assurance.

“In 2014, we were in power in only four states. As of now, we have a government in 20 states. The BJP had a membership base of four crore then; today, we have over 10 crore members. Our social schemes—Ujjwala, Ayushman Bharat, Saubhagya and Swachh Bharat Abhiyan et al—have impacted nearly 20 crore poor. On top of it, the Opposition hasn’t been able to get its act together. Mayawati snubbed the Congress by refusing a tie-up for Madhya Pradesh, and decided to go with Ajit Jogi in Chhattisgarh. Congress toh BJP ki ideology par chal padi hai (The Congress is following the BJP’s ideology). Why should anyone vote for the imitation when the original is there?” he asks, alluding to Rahul’s temple run and claims of being a “better Hindu”.

Social Welfare Schemes

Among the reasons the BJP leader reels off, the party is banking most on its welfare programmes. In this, the BJP may have taken a leaf out of the Congress’s book. “The UPA returned to power in 2009 only because of NREGA and the Rs 60,000-crore farm loan waiver,” admits a BJP leader from Uttar Pradesh. In fact, less than two years into power, the BJP government changed its stance on the job guarantee scheme. From describing it as a “living monument of failures”, Modi was forced to term it as “the nation’s pride”. By that time, feedback from grassroots leaders about the scheme’s efficacy—even RSS cadres vouched for it—persuaded it. From being believers in the trickledown theory—that government should invest in infrastructure and successful sectors will stimulate the economy—the BJP moved big into targeted intervention.

“The government realised in its second year that schemes are needed to touch the lives of the poor,” explains another BJP leader. “So, along with roads, hospitals and schools, the government started its welfare schemes. Building infrastructure is seen as the government’s duty—something that stimulates the GDP—but constructing a toilet or empowering a woman with an LPG cylinder creates gratitude.”

So, the BJP may wield more contentious issues in the public sphere—with party chief Amit Shah upping the ante on NRC in Assam and Sabarimala in Kerala, even daring the Supreme Court (see boxes). But away from that, the government has tried to create and harvest this sense systematically. It has done its maths on how its welfare schemes will create political capital. As per the BJP’s estimate, nearly 20 crore poor families have been unique beneficiaries of various schemes. Assuming that an average beneficiary household has three voters, the party then has managed to reach out to 60 crore voters.

“Among these 60 crore, we may even discount around 10 crore Muslims since the community is not known to vote for the BJP. But even if we have a 50 per cent strike rate, we will still get 25 crore votes, that’s eight crore more than the 17 crore we got in 2014. Then we have our 10 crore members and two crore new voters on our target list,” a party number-cruncher tells Outlook. Not to leave things to chance, the BJP will set up 200 call centres from where professionals and party workers will reach out to scheme beneficiaries to ensure their support in the Lok Sabha polls.

Dalit and OBC Outreach

Contrary to popular ideas of alienation, the largest sections among welfare beneficiaries are Dalits and adivasis. “It’s not by design. It’s simply because poverty is highest among them,” says the party leader from UP. And the party has indeed gone out of its way to assuage any possible anger among these segments. This is vital to their plans, especially in UP where it may battle a conjoined Dalit-OBC front. In 2014, the BJP had managed to stitch together a social coalition of Dalits, OBCs and adivasis weaned into the saffron fold. In UP, this proved to be a game-changer and the BJP won 71 out of 80 seats, with non-Yadav OBCs and non-Jatav Dalits plumping for Modi. “It’s common sense that one can’t overlook OBCs and Dalits,” the leader from UP explains. OBCs make up over 50 per cent of India’s population; Dalits and adivasis account for another 25 per cent. “A political party ignores that at its own peril,” he adds.

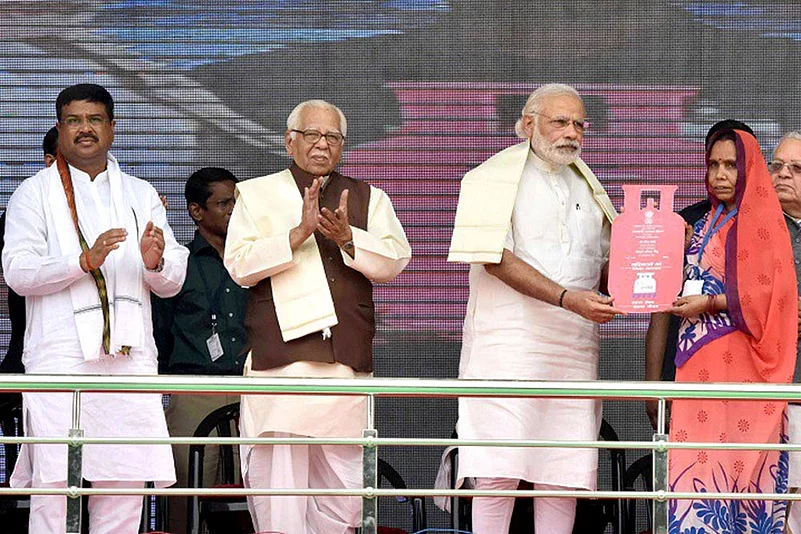

A Ujjwala scheme beneficiary with PM Modi, Ram Naik and Dharmendra Pradhan

That’s the reason why the BJP granted constitutional status to the National Commission for Backward Classes. And, after dithering with its natural savarna inclinations, it also passed the Bill to overturn the Supreme Court order diluting the provisions of the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. In addition, the BJP has moved on the sub-categorisation of OBCs to ensure more equitable distribution of quota benefits—targeting a substantial number of non-dominant OBCs who, the BJP believes, will lean towards it and away from dominant-OBC parties born in the Mandal era. As for any savarna disaffection on account of all this, it plans to keep them happy with the flame of Ayodhya burning.

Yes, that genie is out of the bottle again, at the right time. The apex court has deferred any further action to January 2019, but the “delay” itself is grist to the Hindutva mill and hence useful. The usual choristers—Giriraj Singh, Uma Bharati, UP chief minister Yogi Adityanath—are loudly demanding a law or an ordinance. Other leaders concede legislation may not be feasible, but the brouhaha helps to keep the kettle boiling in the home stretch. “It will expose the Opposition’s ambiguity and allow us to assure our old savarna voters that the BJP has not given up on its core agenda,” says a senior leader. Sabarimala falls plum into this kaleidoscope. Others may believe Hindutva is a double-edged sword, and cavil at the BJP’s peristent communalising of the poll pitch. For the party, it’s the mortar that keeps the bricks together.

Modinomics

This was the real test of the pudding. Demonetisation, of course, was a spectacular disaster: if there’s anything resembling a consensus on any issue in India, it’s this. DeMo was hugely disruptive, failed to weed out black money and caused immense harassment to the common man. Some initial electoral benefit did come—like in the UP assembly polls—but soon it was clear the unconscionably rich had actually not been penalised, as per the spiel. But apart from DeMo?

Over 35,000 farmers marched towards Azad Maidan, Mumbai, from Nashik in March

First, the GST, its other big policy move. GST took the BJP to the brink in the Gujarat assembly polls; only some last-minute changes saved it. Hasty implementation hit small traders, who complain of tedious processes and harassment. “The GST is not bad per se. Some rationalisation needs to be done to prevent tax evasion, which continues unabated in new forms. Even Rahul Gandhi, who childishly calls it the Gabbar Singh Tax, is forced to admit it’s a good thing in principle,” says a finance ministry officer involved in the implementation.

Large-scale unemployment and farm distress still haunt the BJP. The party claims nearly five crore farmers got their crops insured under the Fasal Bima Yojana in 2018, but its implementation in the previous years does not inspire confidence. Insurance companies collected a gross premium of Rs 22,180 crore in 2016-17, but paid out only Rs 12,949 crore as claims. Even promises on MSP remains unfulfilled. These issues will play out in the winter elections, especially in Rajasthan, and some pessimism there is warranted, and the prospect of a negative momentum for 2019 looms too.

Assembly Elections

This is where the slog overs begin, and the party is keenly aware of that. “It has become a cliché to term all assembly polls as the semi-finals. It may well be so, but we are not unduly worried,” a BJP general secretary tells Outlook. “We know Rajasthan may be difficult for us, but we haven’t given up. It will depend upon ticket distribution.” He is rosier about Madhya Pradesh, despite the three-term anti-incumbency against CM Shivraj Chouhan. He expresses concern about Chhattisgarh, though, where he feels the Ajit Jogi-Mayawati alliance has made the fight tougher.

Political analyst Manisha Priyam says the assembly polls are more crucial for the Congress. “If it fails to win Madhya Pradesh in a direct fight with the BJP, one might as well write off the party. Then 2019 will be BJP vs regional parties,” she says. According to her, the anti-incumbency factor is extremely high against Chouhan, but the Congress, beset with infighting, doesn’t seem to be up to wresting the advantage.

About 2019, Priyam says there is a “strong chance” Modi will be back as PM—for one, despite being hobbled by some governance issues, pro-poor schemes are on track. “There are no big scams. They have held the states they won in 2014, including UP. They didn’t win big in Bihar then, but now have an alliance there…and Nitish Kumar is not unhappy. Shiv Sena is unhappy, but still with them. They have lost the TDP, but, who knows, Jaganmohan Reddy may go with them. The mood in the Hindi heartland will be clear soon. The BJP is not in power in the south, but neither is the Congress. Keeping prejudices aside, it seems Modi will be back in 2019,” she says. Then those unquantifiable ‘surface’ factors: Modi’s personal appeal hasn’t dimmed, Rahul is yet to fully bloom, and some voters do dread a ‘khichdi’ government.