In 1984, Kanshi Ram founded the Bahujan Samaj Party, just in time for his young colleague Mayawati to stand for a parliamentary seat in a byelection the next year. Twenty-five years on, the electoral achievements of the BSP and of Mayawati herself have been extraordinary. It is doubtful that in 1984 Kanshi Ram could have done so much as even daydream of dominating the politics of India’s largest state. With the limited exception of the still young Ram Vilas Paswan from Bihar, at the time there was no strong, independent Indian leader of Dalit origins.

Kanshi Ram was already middle-aged in 1984 and a veteran organiser in Maharashtra, the heartland of Dalit politics of the 20th century. As a young science graduate, he had moved to Pune from Punjab—his family was Raedasi Sikh, from a Chamar community converted to Sikhism—to take up a position reserved for the scheduled castes in the defence production industry. In Pune, he soon gravitated towards associations of the Dalit followers of Ambedkar. D.K. Khaparde, who became Kanshi Ram’s closest colleague and friend in Pune, recalled to me the electrifying effect that a reading of Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste had on him. Kanshi Ram was instantly radicalised by Ambedkar’s attack on caste and on Brahminism in particular.

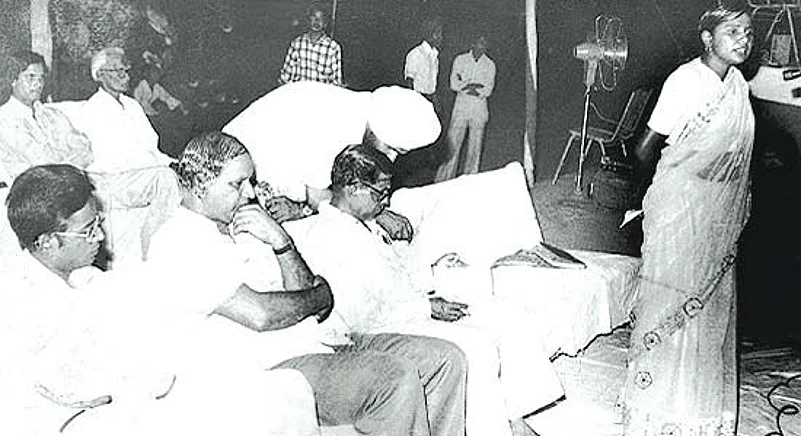

The other radicalising event in Pune was the encounter Kanshi Ram had with discrimination. He told me that he had never personally encountered the practice of ritual untouchability while growing up in Punjab but he soon saw it at work in Pune. On one occasion, he became so incensed with the discriminatory treatment of a young Dalit woman that, in Khaparde’s account, he struck an officer in the face. Khaparde said that by then Kanshi Ram had already lost interest in his own career and did not even bother to attend disciplinary hearings that were called in the matter. Instead, he was happy to turn to promoting Ambedkar’s teachings and the interests of Dalit employees.

Kanshi Ram represents the critical bridge between the intellectual works and political organisation of Ambedkar in western India and the contemporary Dalit politics of northern India. Till Kanshi Ram came along, Ambedkar was a remote and largely forgotten figure for legislators who occupied reserved seats outside western India. Indeed, it was only after Kanshi Ram and Mayawati began to make an impact that Ambedkar’s photographs began to appear on the walls of the New Delhi residence of Ram Vilas Paswan. Ram Vilas was just adapting to the shift of consciousness that was taking place among people who were now increasingly being called ‘Dalits’ rather than ‘Harijans’ or ‘scheduled castes’.

Kanshi Ram’s ideological formulation was presented in easily understood language: 10 per cent of Indian society rules the remaining 90 per cent, the bahujan samaj of Phule’s writings. Although the ruling 10 per cent is composed of several castes, they draw their legitimacy and ruling ideology from Brahminism. All the ruling institutions of society, including the press, reflect this ruling ideology, which he called Manuwadi or Brahminwadi. It was the task of a transformational political movement to bring together as many of the oppressed 90 per cent of society as it could. In some ways, Kanshi Ram’s political approach harked back to Ambedkar’s approach during his Independent Labour Party days in the 1930s, a leftist period when Ambedkar was intent on building a coalition of the Dalits and other subordinated communities in India. When this approach failed, Ambedkar retreated and sadly ended his political career as little more than a leader of the Mahars.

There are those who tried to dismiss Kanshi Ram as a thug. A couple of times, regrettably, he did physically lash out at those who bothered him. There was the incident in Pune mentioned above and then a later case involving a journalist in Delhi. On the second occasion, a section of the press came to refer to him as ‘Punchy Ram’ for a while. True, these acts of minor violence were not pretty. But nor did they really amount to a pattern of conduct that rendered Kanshi Ram unfit for public office. His later years were a tightrope act: he was a participant in national affairs but he was also a deliberate and symbolic disrupter of the status quo. Inevitably, this brought down a volley of brickbats on his head. This is not an excuse for bad behaviour but it does represent a context. Both Kanshi Ram and Mayawati have been subjected to more abuse and disparagement than is usual even for politicians. They are despised and feared almost in equal measure.

Kanshi Ram was far too ambitious a politician to wish to settle for what he saw as the condescension behind reservation of jobs in the public sector for the SCs. “Once the bahujan samaj get to power throughout India, it will be they who can condescend to the Brahmins by giving them reservation proportional to their own (meagre) population,” he told me in the late 1990s, with more than a little bravado. For it is doubtful whether the BSP could have grown as it has without reserved constituencies for SCs. He was also ignoring the fact that his political education was a consequence of his holding a reserved position in government. But Kanshi Ram’s point was that he and the BSP did not stand for a sectional or token advantage for ‘their’ people. Like Ambedkar the theoretician, he was about transformation, not scraps from the high table.

Perhaps Kanshi Ram’s greatest political strength was his mastery of political symbolism and a related concentration on the mindset of government personnel rather than on policy. The BSP has never bothered trying to formulate a comprehensive programme of policies. The goal has been to capture power and put in place like-minded officers who will then, seemingly almost reflexively, remake government and society so as to serve the bahujan samaj. IAS officers have been transferred within UP in record numbers in order to align government with the people. Enterprises like the erection on Lucknow’s streets of statues of Ambedkar, Periyar and even Kanshi Ram and Mayawati themselves have been portrayed as necessary acts of consciousness- and confidence-raising for the bahujan samaj.

Elevated!: Erecting statues in UP is portrayed as an act of Dalit confidence-raising

One of the persistent criticisms of the BSP governments is that they have been unusually

corrupt. Such censure is virtually impossible to evaluate but surely it is possible that a party of outsiders like the BSP may be more obvious rather than more greedy in its monetary extractions. There are established avenues even for siphoning off of funds, and the BSP has made a virtue as well as a necessity of not travelling down the beaten path. And, until the assembly elections in 2007, BSP leaders knew that their governments existed on borrowed time, and so perhaps there was an urgency to the seemingly universal party imperative to collect funds. Might there not be an element of truth in Mayawati’s claim that a BSP government is judged by standards not applied to governments of parties led by those higher on the social ladder?

The formation of the first Mayawati government in 1995 resounded like a thunder clap around India. Mayawati was not the first Dalit chief minister in India but she was the first to run a government whose rationale was service to the most subordinated caste communities of the state. We have become so used to the Mayawati phenomenon that it is hard to remember the mix of excitement, horror and disdain that her elevation provoked. Could Kanshi Ram really have believed in 1984 that such an event was possible? And could he have envisaged the triumph of 2007, a year after his death, when the BSP came to power with an absolute majority in India’s largest state? (He would not have been so happy with the Lok Sabha elections of 2009, when the party’s tally remained almost static from 2004 and, with one exception, confined to UP.)

The post-Kanshi Ram BSP is now at an important crossroads. The party fairly successfully repackaged itself in 2007 as the champion of all subordinated people in UP, whatever their caste or community. This relatively orthodox leftist position was the culmination of a change in rhetoric and distribution of seats occurring over a number of years. The BSP has now learnt to reach out to a wider caste constituency without losing its Chamar base. (At the same time, throughout India the Communists, who refuse to talk about caste at all, are sinking.) But the price of heightened electoral success will be more insistent demands for the delivery of material progress on the manifold economic and social problems of UP. Levels of literacy and other measures of prosperity remain significantly beneath the national average and well beneath perhaps comparable states like Tamil Nadu. Those who constitute these lagging measures are the Dalits and other members of the bahujan samaj. This is not a problem that will solve itself. So successful has the BSP become that it now urgently needs the policies that Kanshi Ram treated as a kind of self-indulgent irrelevance.

'84: Kanshi Ram launches party with socialist leanings to represent the ‘bahujan’, or the people in majority

'09: Mayawati gets added impetus with ‘Sarvajan’; gets into a tangle over expensive, narcissist public structures

(Oliver Mendelsohn is the author of The Untouchables: Subordination, Poverty and the State in Modern India with Marika Vicziany, Cambridge University Press, 1998.)