American President Barack Obama’s forthcoming visit to India reverses the period of indifference with which Washington treated New Delhi and should help normalise relations between the two countries. Long before India tested its nuclear weapons in 1998, Washington would hardly hurry to appoint its ambassador to New Delhi. During the 1971 war that created Bangladesh, the United States sent its aircraft carrier, much to the disgust of the Indians. Later, following India’s “peaceful” nuclear explosion in 1974, an annoyed America established the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), an export cartel aimed at, among other things, curbing India. Indeed, for a long time, “the strongest democracy” showed not much respect to the world’s “biggest democracy” because of its nuclear quest.

True, China expressed regret, reasonable though it was, over Pokhran I and Pokhran II, but it never sanctioned India, believing such methods are neither effective nor helpful to settling international disputes. Another reason for China’s stance lay in the fact that western powers had tried to contain China also through sanctions. No wonder then, even when the NSG was trying to curb India, China expressed its opposition to the NSG rules, asserting that all countries have the right to peaceful use of nuclear energy.

China joined the NSG in 2004 and accepted its rules the same year. But before it joined the NSG, China insisted it wouldn’t enforce full-scope safeguards in its nuclear cooperation with those countries that hadn’t signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). This meant that non-NPT countries weren’t required to allow the International Atomic Energy Agency access to all their domestic nuclear programmes, including those pertaining to military, before they could work with China on the civilian side. Consequently, China was able to skirt around the NSG rules to provide India low-enriched uranium in the late 1980s. In other words, China assisted India’s civilian nuclear programme two decades before the US changed its mind on the issue.

America’s distancing from India deprived the latter of adequate international assistance to power its economy. By contrast, China believed that India and other developing countries, regardless of their N-status, deserved international cooperation to improve the quality of life of their people.

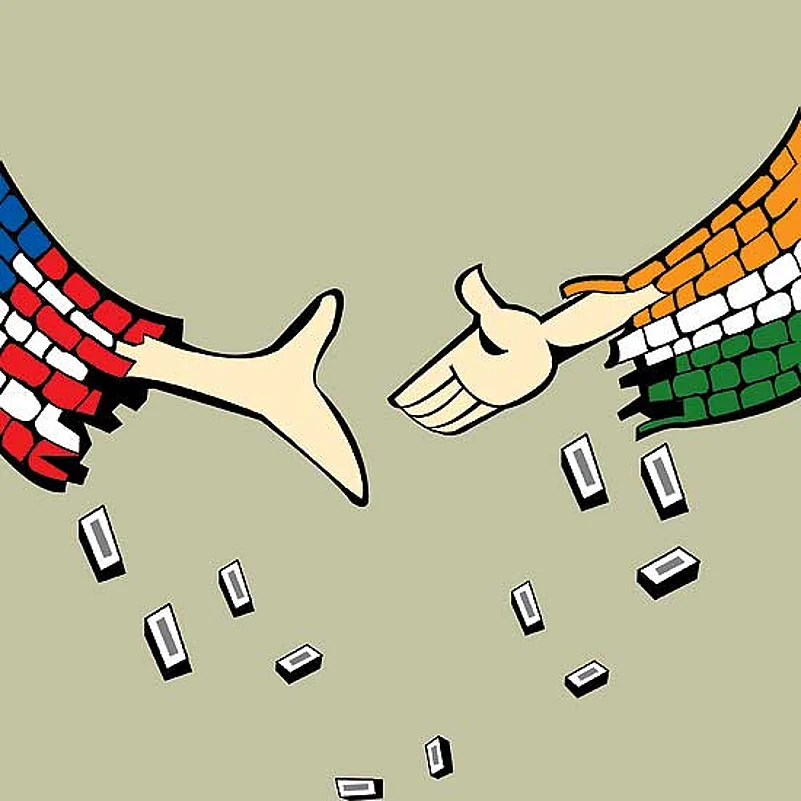

The end of the cold war saw improvements in Indo-US ties—and this had a beneficial impact on international relations. However, Indo-US relations have improved not because Washington has forsaken its old mentality. Just as America was indifferent to India due its proximity to the erstwhile Soviet Union, Washington is now demonstrating greater warmth for New Delhi out of some concern over China’s rise.

Some members of the strategic community in Washington have repeatedly voiced the need to check and balance China through the strengthening of traditional alliances and fostering of new ones. America’s desire to work with India is clearly part of this game, suiting as it does both of them. The sheer momentum with which China seems to be catching up with the US has prompted it to hedge its bets and spread its risk. For New Delhi, cooperation with America is reassuring because of the ever-widening economic gap between India and China.

To be honest, should China deviate from its professed peaceful development, the ongoing rapprochement between the US and India would indeed help temper Beijing’s behaviour. Other than this, Indo-US relations have limited value. After all, India’s competitiveness fundamentally comes from its institutional innovation and economic productivity—and not mainly because of its association with the US. Similarly, America’s competitiveness and leadership originates from its own creativity, rather than from checking China through India and others.

Beijing trusts that India, which is a fount of profound wisdom, will adhere to pursuing an independent foreign policy. While a more normal Indo-US relationship is welcomed by all, it will be prudent to understand a fundamental difference between the two countries. India will not support the US policy of going to war against another country with or without the backing of the UN—as it didn’t in the case of the invasion of Iraq in 2003. This underlines a fundamental divide between India and the US.

There is no reason for China to worry over improving Indo-US ties. After all, President George W. Bush visited China four times during his two terms in the White House. The US has cooperated with China, as a nuclear weapons state, on peaceful use of nuclear energy. Their cooperation wasn’t aimed at containing India. Likewise, should Obama get another term and visit India four times, Beijing won’t perceive it as a policy to contain China. Really, it is too expensive a proposition to contain too big a power as China or India.

(The author is Director, Center for American Studies, Fudan University, Shanghai)