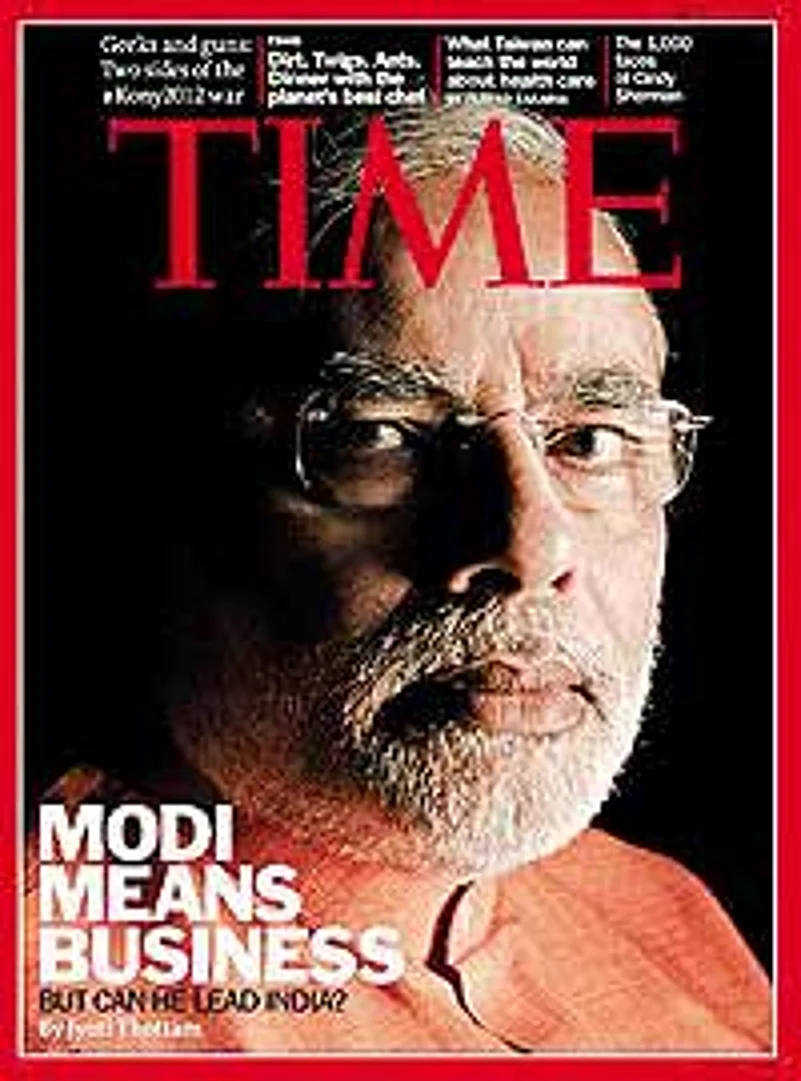

Narendra Modi is no doubt a successful politician. There is almost a special kind of luck that accompanies him in the public domain, luck that can be explained in two decisive electoral victories and the attraction that follows such success. He is constantly in the news and a set of those who fear and adulate the man suggest that the more the institutions of justice berate him, the more his TRP soars. News constantly props up the picture of a decisive chief minister. Last week, Time had him on the cover and Brookings Institution had a favourable report on him. There is a curious timing behind these reports. They hint that he is prime ministerial material and that a realistic sense of politics demands that one engage with the emerging Indian future.

One can match statistics with statistics to show that Modi’s achievement is exaggerated, that other states have done well or that GNP and GDP could take contrary turns in Gujarat. One can say, for instance, that in the five years between 2004-05 and 2009-10, Gujarat’s per capita income nearly doubled from Rs 32,021 to Rs 63,961. In the same period, neighbouring Maharashtra, the perceived laggard, saw its per capita income grow from Rs 35,915 to Rs 74,027. Several states besides Gujarat have shown double digit growth in their GDP in recent years, and Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh have bigger economies. Gujarat now runs a revenue deficit—it spends more than it earns—and its surplus has disappeared. Several other states have improved their fiscal positions meanwhile. Reforms? Five states passed the Fiscal Responsibility Bill before Gujarat did in 2005, and 20 states preceded Gujarat in implementing VAT. Surplus power? Facts on the ground and increasing protests show this to be an exaggerated claim. Human development indicators? Gujarat lags behind in access to primary and higher education, is high on the percentage of population prone to hunger and starvation, access to fiscal credit among the marginalised is low, girl child schooling shows poor figures. State and central government figures support all this.

We think there is also a different way of responding—by asking what is the criteria for decency and well-being? One has to go to the structural roots of the argument, move beyond a gasping portrait of Modi already basking in a future at Lutyens’ Delhi. Time magazine’s two-page picture of Modi on the lawns is suggestive of that. It is as if the props are there, the script is also there, the players are waiting, and all one needs is an auspicious time. The Brookings essay on Modi goes one better and writes him a certificate of good conduct that would help revoke the ban on his US visa. For Brookings, banning a future prime minister would be bad politics.

Time cites a social scientist in a preemptive act, a jumping of the gun proclaiming a once and future king before the democratic and legal process is over. Indian courts are yet to assess whether the evidence collected by investigators and assessed by the amicus curiae appointed by the Supreme Court can make out a case to prosecute Modi, his cabinet colleagues, ideologues, administrators and policemen. The charges are criminal culpability to conspire to commit mass murder, subvert the justice process and destroy critical evidence and records. Why then, we may ask, the unholy haste by Time magazine and the Brookings Institution when courts are seized of the matter, Modi could (or may not) be charge-sheeted for criminal offences, when general elections are nearly two years away?

The analysis presented states that Muslims are voting for Modi as the Congress is too weak to do anything for them. The question one has to ask is: Is such a lazy social science enough? Which section of Muslims is voting for Modi? Two, is a vote for Modi a legitimation of Modi or is it a shotgun wedding of a community that is desperate to survive and see that its people still wrongfully locked in jail are released?

Anyone who watched the Sadbhavna festival would realise that the Muslims who came were paying court to a king. There was no rapprochement, no forgiveness. If anything, the ritual expressed its distance from Muslim life. The Sadbhavna yatra was more a power game like ancient times where people swore fealty to the lord. The state government, in the ultimate display of control, has refused activists access to accounts of the public monies spent on an autocratic chief minister’s personal agenda.

One has to read the metaphors of the Time report. Modi is presented as wearing the white of a penitent embarking on fasts. The writer, Jyoti Thottam, suggests it’s an act of purification,

humility and bridge-building. To read Modi’s Sadbhavna fasts in this way insults the idea of fast as a moral weapon and confuses it for a strategic tool. White, anyway, is the most hypocritical colour of politicians. The question one has to ask before one uses words like humility and purity is: What is the moral nature of the act?

But Modi should not be seen only a personality. He is a Rorschach inkblot set before society, provoking basic questions. Modi, in terms of civic indicators like investment, rule of law and governance is scoring high. These statistics have been rigorously contested in the public domain, by the Gujarati media, by the opposition, even the state government’s own figures. And what about the CAG reports on Sufalam Sujalam project, the Kutch melas and the public disinvestment scams? A dispassionate assessment exposes the Modi makeover for the brazen public relations job it was meant to be.

And then how does one look at and talk about his institution-building? He has refused to allow the Lokayukta to function freely. He has silenced the bureaucracy with threats, incentives of plum posts, juicy extensions that let senior bureaucrats retain power and visibility. His privatisation of medicine has to be independently assessed in terms of ethics, care, cost and well-being. Ahmedabad, home to at least four universities and some of the finest institutes, still cannot produce a critical debate on him, as many institutes have quietly imposed a gag order on dissenting intellectuals. The Congress, though weak as an opposition, has highlighted a major issue. Land is being bequeathed to major corporations like Tatas and Adanis on easy terms, transforming public lands into private goods. At the Gujarati taxpayer’s expense.

The Brookings narrative adds a second halo to Modi. It converts him tacitly from a politician to a statesman receiving courses on climate change and even writing a book on it. Behind both essays is an even more tacit semiotics. It is what we must call the Americanisation of Modi. It creates a political palatability to his reception abroad. Leave aside the American’s love of the Asian dictator with a keen and ready investment plan, there is first the Horatio Alger syndrome, portraying him as a self-made man, as a protestant ascetic, a journey Time portrays in the from-smalltown-boy-to-CEO-of-Gujarat, succeeding without family connections or fancy education. He seems very different from the young Congress elite, with their pampered backgrounds. Unlike other Indians, he keeps his family at a distance. There is no family coterie hanging around him, unlike around Laloo Prasad Yadav or Karunanidhi or Yediyurappa. The Brookings report then steps in by showing Modi to be a keen student of American politics, wondering whether Indian states can have the sort of freedom states in the United States do. He is entrepreneurly, eco-friendly, and all in all, a global man awaiting his time, open to World Bank reforms and yet a home-grown nationalist. Modi is also presented not just as prime ministerial material but as the Indian answer to China, a note that will play deep into the American and Indian psyche, presenting them a streamlined politician for the future.

The question one is asking is not whether Modi is a future prime minister. The logic of Indian electoral politics will answer that. The question is: Where does Modi fit into a vision of decent society in which the minorities and those in the margins have a place, in which dissent has a place? Is Modi’s future a participative future and a pluralistic one? His technocratic credentials are not in doubt, but his vision of democracy needs to be examined. Oddly, Modi might fail by the norms set by his own hero, Swami Vivekananda. Modi has failed to provide a civilisational answer to the crisis of Gujarat. Investment and development, even with the distorted statistics bandied around, are poor substitutes for such a vision. In Americanising him, the reports reveal the modernist flaw deep within his programme.

(The authors are trustees of Citizens for Justice and Peace)