Manzur had a great deal to say about terrorism and jehad. Dismissing the terrorists with contempt, he said: "Unki dukan band hone wali hai (their business is about to go bust)." He also dismissed their claim to be waging a jehad. "If someone prevents me from saying my namaaz or going to the mosque, then it is my duty to wage jehad. But if I can pray whenever I want; if the mosques are open and I can hear the azaan five times a day; if no one interferes with my customs and ceremonies, then where is the need for jehad?" Thus did Manzur consign scores of learned tomes and think-tank papers, containing hundreds of pages of rationalisation, to the waste paper basket. Mohammad Usman, Mohammad Suleiman and the others nodded sagely.

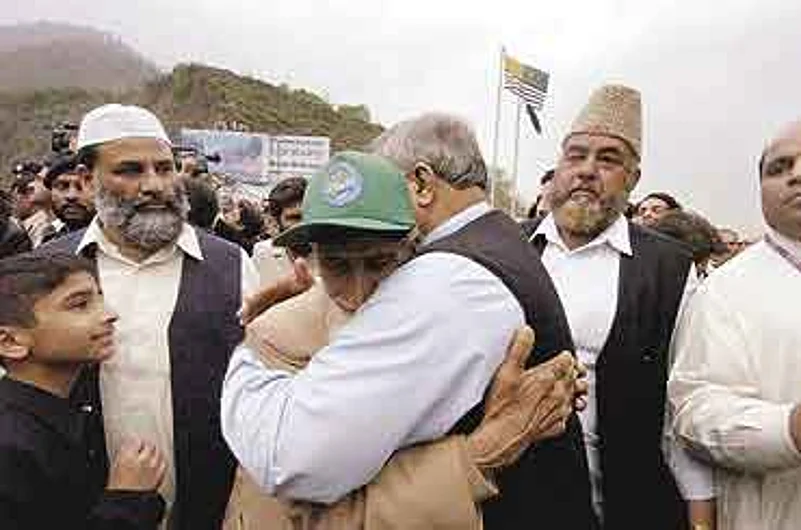

At last, the Muzaffarabad bus arrived. It stopped at a bend in the road for the exit formalities, and then inched forward to the bridge, preceded by scores of Pakistani journalists and local notables. A white flag was lowered at each end, the gates opened and the walk to reunion began.

On the way back to Srinagar, the visitors' buses were forced to halt at Salamabad where a 10,000-strong reception party was waiting for them with a Kashmiri wazwan. As a result, ours was the first vehicle from Kaman post on the road for the next 50 kilometres. We, therefore, had a ringside view of the huge crowds, the holiday mood that enveloped them, the colourful dresses and excitement of the women and the rough good humour of the men in which, for almost the first time in 15 years, I found myself included. Between Sheeri and Baramulla, 25,000 people crowded the road, and the roofs and balconies alongside it. All security arrangements had broken down and the army could do nothing but mingle with the crowds and hope for the best. What struck me was the absence of hostility, and fear. It was a far cry from the silent streets, the blacked-out nights, the 24-hour curfews and the blaring loudspeakers of the mosques, of 1990.