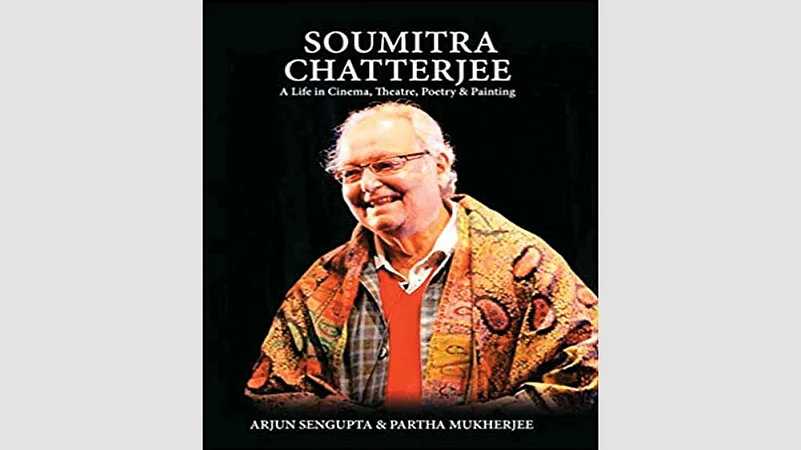

Soumitra Chatterjee’s life is so full that it is difficult to cover it through a logical timeline. The various Soumitras jostle for space—the actor, the thespian, the artist, and the poet. In a definitive book on him, it is also imperative to dedicate a substantial portion to Soumitra’s relationship with Satyajit Ray who, apart from directing him, was a mentor and guru. This book covers the many Soumitras through research and anecdotes.

The book opens with Soumitra’s birth and childhood in Krishnanagar, along with the many influences in his life. He of the generation that experienced Independence and witnessed the artificially created famine that devastated Bengal that was later to influence him in his lead role in Ashani Shanket. Soumitra’s family was fond of poetry and linked to the freedom movement—the famous revolutionary Bagha Jatin was his father’s nephew. Since boyhood, Soumitra displayed a fondness for oration and was influenced by the words of an Englishman who spoke about acting in a visit to his school. The association with the great director-actor Sisir Kumar Bhaduri added lustre to his burgeoning talent, along with his discovery of Part 1 of Stanislavsky’s ‘method’.

In Calcutta, he was introduced to Satyajit Ray by a friend who was part of Ray’s production unit. A new episode in his life began with that encounter, though Soumitra began his career with Ray a few years later, in Apur Sansar. His roles in the 14 Ray films are discussed in detail, along with the fact that Soumitra did not shy away from negative roles. The characters of Dr Ashoke Gupta in Ganashatru (An Enemy of the People), Sandip in Ghare Baire (The Home and The World), and of Prashanta in Shakha Prashakha (Branches of The Tree), cover variations from self-recrimination and exhaustion to megalomania and narcissism. He was notably coolly villainous in Gharey Bairey as the smarmy, seductive Sandip--even though critics were undivided on the merit of the role.

The Ray chapters, with touches of lyricism in the writing, bring us to Feluda and what Soumitra brought to the role of a Bengali detective designed for children, a character that had a lot of Ray in him and which Soumitra gradually began to shape in the passage of time between Sonar Kella (1974) and Joy Baba Felunath (1978).

After Ray’s passing, the authors cover Soumitra’s work with other directors like Tapan Sinha and how his career was diametrically opposite to that of Uttam Kumar, the superstar of Bengali cinema. Uttam Kumar started being in cast in meaningful roles after he attained stardom; for Soumitra it was the other way around. The importance of narrative in the Bengali film context is underscored along with the fact that Bengali cinema in the ’80s began to lapse into a certain mediocrity and Soumitra was forced to take on roles he did not approve of because of financial concerns. However, there were films like Kony and Belasheshe that made their mark.

Theatre remained a love and the book takes us through his definitive theatrical performances, including Raja Lear, possibly the most outstanding of them all, though the production was tarnished by bickering over finances, generous accolades notwithstanding.

In later life Soumitra was able to devote time to his poetry—there are English translations from some of the poems that do little justice to the original, but convey his poetic preoccupations and the strong influence of Tagore. That he was a painter and made 140 sketches and paintings inspired by his costumes and theatrical roles and that his own art was lauded is covered too. A renaissance man of sorts, he has been called a bridge between stardust and reality by Dhritiman Chatterjee.

Unfortunately, this well researched account of Soumitra’s life does not bring closure with his recent death, as it possibly should have done, with a final touch of sad completion, to highlight the meaning of his passing to the Bengali cultural ethos.