The iconic 40-seater Lockheed Martin Constellation took off from the Mumbai (then Bombay) airport for London, on the warm summer afternoon of June 8, 1948—just 10 months after India’s independence—carrying 35 people, including ‘maharajas’, ‘nawabs’ and J.R.D. Tata. It was India’s maiden international flight, and for JRD it was a moment of pride (Air India was owned by the Tata Group). He went on to build the country’s largest salt-to-steel conglomerate, touching almost every household in the second most populous country.

When he took over as the chairman of Tata Sons (holding company) at the age of 34, there were 14 companies under the umbrella, with $100 million in assets. Half-a-century later, when he passed on the baton to Ratan Tata, the group had a web of 95 companies with $5 billion in assets—and had ventured into businesses like software (TCS), healthcare (Tata Memorial Centre of Cancer Research and Treatment) and education (TISS).

Buried in this corporate history is the story of India’s social, political and cultural evolution. The nationalisation of Air India and the launch of Lakme showcase the priorities under Jawaharlal Nehru. The first marked the focus on public sector assets. The second was about the penchant for import substitution in a planned economy. Lakme was born when New Delhi dialled the Tatas in the 1950s to improve access to grooming products for the newly-liberated women.

The Industrial Policy Resolution of 1956 laid down the restrictive rules of ‘licence raj’. It was a system that ushered in industrialisation in the Nehru era, but found critics such as B.R. Shenoy and C. Rajagopalachari. “We lost two generations of entrepreneurs because of the tyranny of licence raj. Private companies lost market share in a bureaucrat’s office,” says Gurcharan Das, author and former CEO of P&G India. JRD once told Nehru that the public sector needed to make profits. Nehru retorted, “Never talk to me about the word profit, it’s a dirty word.”

“Nationalisation was a poorly thought out strategy. It not only killed the entrepreneurial spirit, but created inefficient PSUs, which are today staring at gigantic losses and struggling to survive,” says Arun Bharat Ram, the patriarch of SRF Group, with roots in the DCM Group founded in 1889 (the year that saw the birth of India’s first prime minister). “If this hadn’t happened, Indian industry could have become global leaders in many sectors.” Under Arun’s grandfather, Sir Shri Ram, DCM flourished and came to be called the ‘Tata of North India’.

ALSO READ: When Liberalisation Freed India Inc

Movement of Capitalism

Capitalism in the early years was a story of family-owned businesses founded in the pre-independence era. And the long shadow of feuds and eventual splits didn’t spare them. The DCM Group split twice in the 1990s.

“The cracks appeared much before, as ownership and management were confused, and meritocracy was sacrificed,” says Ashish, MD, SRF Group, and Arun Bharat Ram’s son. While many blame greed and lack of succession planning for these feuds, the younger Bharat Ram asks, “Apart from the family business and government jobs, what were the opportunities back then? Capital inadequacy and the licence raj meant family members couldn’t branch out into new businesses easily. Until the mid-1980s, private entrepreneurship was not desired to thrive.”

As the euphoria of the Nehru years petered out, the faultlines of deficit financing and export pessimism started to find wider criticism. By the time Indira Gandhi inherited a weakening economy, cries for economic freedom were being heard. But it took the Janata regime, which rode to power in 1977, to rethink policies. From licences to controls, taxes to subsidies, finance minister H.M. Patel—often ignored by history books—brought fresh thinking into aspects of policy-making. He created committees and set the stage for loosening the bureaucratic clutches.

It became easier to expand industrial capacities, set up new businesses and import technologies. As Sudha Murthy recounts, her husband N.R. Narayana Murthy and six others came together in 1981 to change ‘India’s future with software’. This was a time when even getting a computer meant a bureaucratic tangle, a telephone connection took months, if not years, and ‘Made in India’ wasn’t a buzzword.

Further reforms were ushered in by Rajiv Gandhi, but India was yet to become truly competitive. “Systemic issues remained and capital inadequacies meant a controlled economy,” says N.V. Sivakumar, partner and leader, entrepreneurial & private business, PwC. “In the 1980s, we moved the needle towards trade reforms, but a lot remained to be done.”

1991: Bombay House and Narasimha Rao

As the winds of change blew over Bombay House (Tata Group’s headquarters), 1991 was a significant year. Ratan Tata took over the reins from JRD and a minority government led by P.V. Narasimha Rao liberalised the economy and saved India from an international default. “The 1990s was the story of globalisation. Along with FDI, the new merchants were allowed to enter in the form of venture capitalists and private equity funds,” says Gurcharan Das.

“After 1991, we initially looked at FDI as a threat, but experience and confidence showed us that we could take on conglomerates at home and abroad,” says Ashish. In 2000, SRF acquired its global rival in India, DuPont Fibres, a subsidiary of the American multinational. The year marked the first foreign acquisition by the Tata Group (Tata Tea’s buyout of Tetley). The growth of the auto, pharma and IT sectors followed, which highlighted the resilience among Indian businesses despite being held captive for more than five decades. India’s turnaround into the second fastest growing economy did not take much time.

Mukesh Ambani with his family

Some credit the strong traditions among the Jain, Marwari, Baniya, Parsi and Chettiyar communities, but others lay the credit at the doors of Nehru’s ‘modern temples’, the IITs and IIMs. India’s new IT billionaires and unicorns emerged largely from these institutes.

“The turning point was the growth in R&D. Foreigners stopped selling technology, as we became their competition, so it had to be developed in-house,” says Ashish. SRF’s R&D facility was set up in 2001 and marked a big leap into future growth.

Three decades after reforms, India still draws 70 per cent of GDP from family-owned businesses (as per a recent PwC report). But with 58 unicorns, a digital wave, 41,000 startups raising over $70 billion, has the democratisation of entrepreneurship begun?

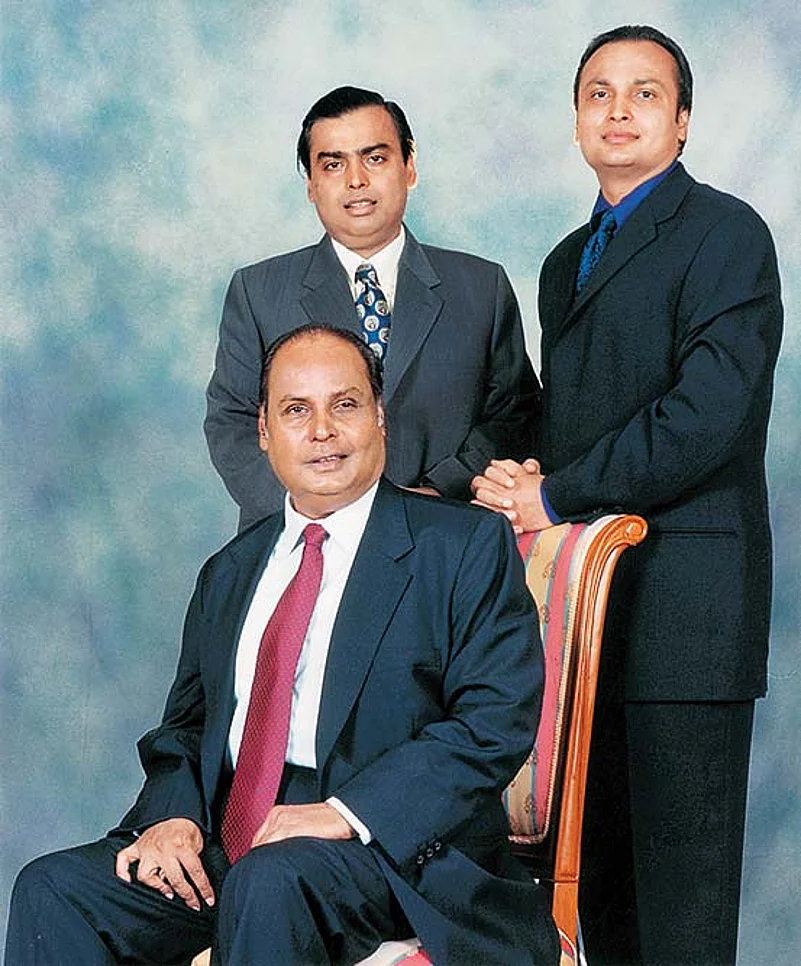

Mukesh Ambani with Dhirubhai Ambani and Anil Ambani

Turn Of The Millennium

Most startups emerged in the context of hi-tech capitalism. According to economic historian Jairus Banaji, the turn of the century witnessed massive restructuring of capital, rise of supply chain management, and the ongoing revolutions in transport, communications and ICT. “Much of the new hi-tech startups is focused on valuations and exits, and is not about long-term organic growth. This is scarcely a democratisation of entrepreneurship in any meaningful sense,” he says.

While India moves up the ease of doing business (EODB) rankings, ground realities continue to stifle new businesses. The true measure of EODB is how fast you can wrap up your business, says K.P. Krishnan, former secretary, ministry of skill development and entrepreneurship. He narrates how in a northern state, the simplification of renewal of licences is held up because it impacts an annual revenue of just Rs 1.7 crore. “The bribe is five times that amount, and local enforcers do not want to part with it,” he adds.

It is important to note that growth of new firms is now witnessed in services. Infrastructure and agriculture are not options. “The answer lies in lower-level bureaucratic tyranny,” says the younger Bharat Ram. A tech startup escapes this by virtue of the nature of its business. “Land acquisition and labour continue to be mired in a complex web of clearances,” adds Krishnan.

In the near future, family businesses will still rule in India. But global research shows that only 10 to 15 per cent of family businesses go beyond the second generation. While it is heartening to see Ashish’s daughter wanting to break away to set up her company to make sustainable cosmetics, for a majority of youth, a stable job is the first port of call.

If Indian capitalism has to compete globally, it has to be based on widely-owned firms, which are professionally-managed. “L&T is a perfect example. It is devoid of family domination, and has professional management and impressive technical capabilities,” says Banaji. “We need more firms of this kind.”

(This appeared in the print edition as "India Inc A Family")

ALSO READ