Telangana: Agriculture extension officer K. Mounika ends her life after her photograph was released on social media and WhatsApp groups for defaulting on her loan taken through an instant credit app. She was 24.

Delhi: Harish, 25, hangs, himself following constant harassment by app-based creditors. His photographs were also circulated on WhatsApp groups.

Kerala: Mother of two Swapna, 32, and her younger daughter, just two-and-a-half, die after consuming poison. Her elder daughter, 11, is battling for life in a hospital. Swapna was shamed and harassed for defaulting on her loan.

These are but mere statistics in a nightmarish world of the predatory loan shark; ordinary people who were scammed by creditors that deal through mobile and digital app-based operations. The ruthless creditors dug into the live bodies of the victims, and tore them apart. Some died, and the rest were scarred for life. Only when the dead were found scattered across the country did the ones who were alive, who should have done something, but did little, sprang to action. As the global expanse of the scandal unravels, the people, who are still stuck in its vortex, may be happy, as they may not have to return the money they borrowed. But those who went through the turmoil are likely to be troubled by thousands of cuts on their minds and hearts.

In retrospect, the industry, police, regulator, media, and public knew about this multi-billion dollar scam. Their actions were in the form of lame-duck exercises to protect against future charges that they did not act. Hence, there were no sustained efforts to curb, or stop the swindle. The scandal continued, and expanded, and engulfed tens of thousands of people, who were harassed, vilified, and abused. Some of them committed suicide, which jolted the country out of inaction, and prompted the police and regulators to pursue the criminals.

ALSO READ: Credit Is Feed For Bigger Fish

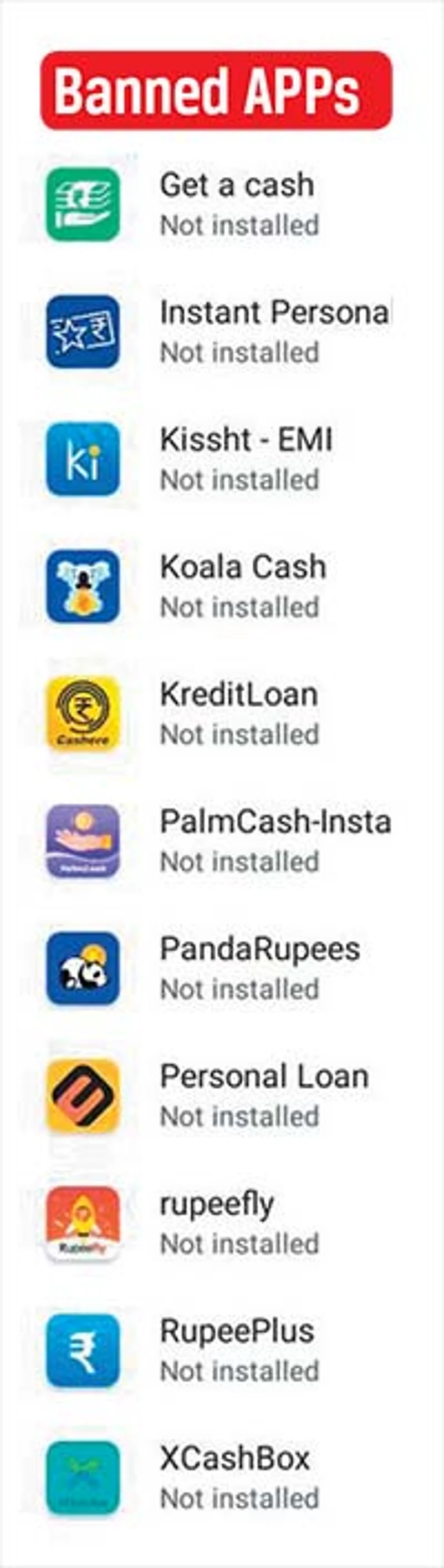

Months ago, the industry was aware of the malpractices perpetrated by hundreds of mobile-digital loan-apps. They targeted the hapless, largely young, borrowers across at least half-a-dozen states. Traxcn, a venture capital tracking firm, estimated that there were almost 500 alternative lending start-ups, which did not include the well-known banks and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs). Most of them were irregular apps—at last count, there were 197, of which 163 have been banned—or digital versions of traditional moneylenders.

Four men arrested in one of the loan scam cases .

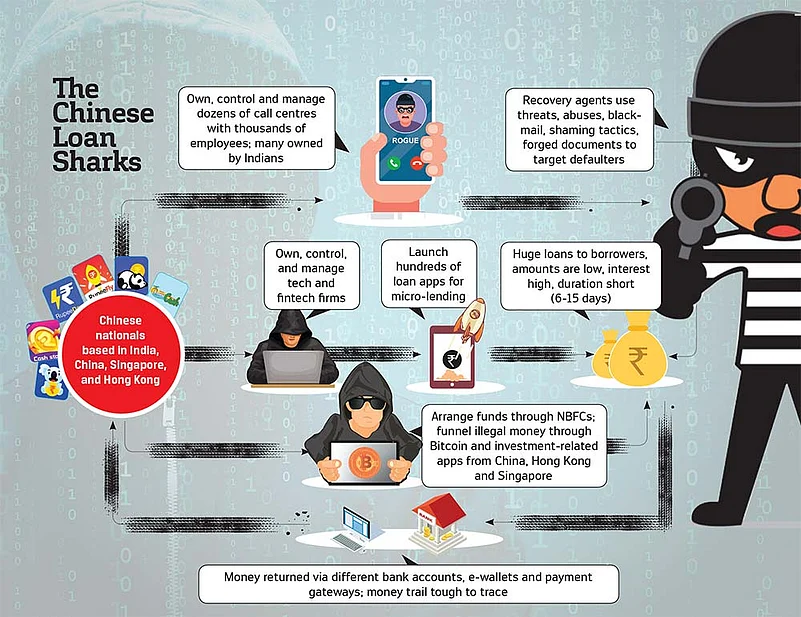

Data from AppsFlyer showed that Indians had the largest number of installs for these apps in the Asia-Pacific region. Some of them were downloaded more than a million times each, which indicated the extent of their reach. Renowned global giants like Google Play Store and Apple Apps openly allowed smartphone owners to access them. Worse, almost two-thirds of these apps were owned, controlled and managed by Chinese nationals, who either lived in India, or were based in Singapore, Hong Kong, Indonesia, and China.

Since last year, the police in several states such as Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, and Delhi received complaints from desperate borrowers, who took money through the apps, and were threatened, and shamed in front of their families, friends, and colleagues. In June 2020, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), issued guidelines to banks and NBFCs, which provided money to the loan apps, to adhere to “Fair Practices Code”. The central bank knew about unfair processes employed by these so-called ‘digital lending platforms’.

In its June 2020 guidelines, the RBI stated, “It has been...observed that the (digital) lending platforms tend to portray themselves as lenders without disclosing the name of the bank/NBFC at the backend (the financier of loans).” The customers were not able to lodge complaints under the existing regulatory framework—either to the banks and NBFCs, or to the RBI. The RBI added, “Of late, there are several complaints against the lending platforms, which primarily relate to exorbitant interest rates, non-transparent methods to calculate interest, harsh recovery measures, unauthorised use of personal data and bad behaviour.” In essence, the RBI knew everything.

Even the media knew. In April 2020, Zee Business, a news channel, conducted a sting operation to expose the nefarious activities of the illegal apps. Thousands of people posted their traumatic experiences on Twitter under several hashtags, like #haftavasooli (weekly extortions). Thus, the larger public knew something was drastically wrong with the micro-lending app segment, which enabled people to take small loans (as low as Rs 2,500) at exorbitant interest (20-50%) for short durations (6-15 days).

The fact that these errors of commission and acts of omission by the above-mentioned people and entities were enormous is visible through a few more numbers. In Telangana, says Shikha Goel, Hyderabad’s additional commissioner of police, Rs 25,000 crore was involved, which included repeated loans. The police froze Rs 350 crore in 435 bank accounts. This is only in one state. Chennai police commissioner Mahesh K.umar Aggarwal says that Chinese nationals “cheated and extorted money” from 25,000 individuals.

Security Breach

In retrospect, however, the stakeholders were unaware of a larger security disaster that was involved in the loan-apps trap. This was the theft of hundreds of gigabytes of mobile data from millions of Indian borrowers, including those who paid and were not harassed. That too by Chinese nationals, who were earlier accused of espionage and spying on eminent Indians that included the President, prime minister and his cabinet colleagues, and scores of public officials, judges, chief ministers, and senior politicians from various parties.

Now, imagine this nightmarish scenario. When one installs the apps, you allow them access to most of the mobile data, which includes contact list, buying habits, and information related to behaviour. For example, the app may know that the user is a gambler, drinker, and active on social media. Even if five million downloaded the Chinese apps, and each had 50 names in the contact list, this implies details related to 250 million, largely young, Indians. This is apart from the Aadhar and PAN details that the actual users gave to the apps.

Remember what Cambridge Analytica, a London-based company, and Russian hackers did with similar information that they gathered surreptitiously from social media accounts of millions of Americans. The Russians allegedly influenced the US elections in 2016, and helped former president Donald Trump win. In the near future, the Chinese may be in a similar situation—armed with the ability to rig elections, and other social and political events in India. The loan-apps scandal isn’t about financial security, but the national one too.

A Supreme Court petition, which was filed by an NGO, Save Them India Foundation, states that the espionage and spying on eminent personalities “comes at a time when New Delhi and Beijing have been engaged in a stand-off since April-May (2020)”. It adds, “China, not only through one mode, but by other modes like money lending apps is extracting the data of Indian citizens and storing there in its country. This could have a disastrous effect in future, and it is also a threat and danger to our national security and integrity”. Pravin Kalaiselvan, chairman of Save Them India says, “ With this episode it's all the more necessary to approve (the) data protection bill. Those arrested will be charged with financial fraud although it's a data theft fraud too. ”

Thus, an understanding of the nitty-gritty and details of the loan-apps scandal is crucial. It is not merely about criminal acts, which targeted unaware victims. It has a larger purpose, which can unravel over the next several years. The second is more important because the ban on most of these apps, and investigation into the others, may help the borrowers, who may not have to repay the money. But the data may be gone forever. In this century, where cybercrime and data theft can act as weapons of mass destruction, India isn’t safe.

Tap and Borrow

Blame it on COVID-19, which led to the loss of millions of jobs, salary cuts and delayed payments. Caught in a vicious cycle, many Indians hungrily and desperately scrounged for help. Voila! There were hundreds of digital-mobile loan apps willing to extend money in a jiffy. A consultant in Telangana says that her first loan of Rs 2,500 was transferred in 10 minutes—“no hassles, no documentation, just a few clicks to send photographs of Aadhar and PAN, followed by a live selfie”. Hence, millions of young Indians, who needed short-term loans, generally for small amounts, were addicted to the apps.

At this stage, human traits related to desperation, greed and unusual confidence kicked in. The money was easy to get, the interest rates were a high 20-50%, calculated on a daily or weekly basis. Fascinated by the ease of getting money, many borrowed recklessly. They took small amounts, but from as many as 50 apps. Kirni Mounika, 24, who consumed poison and died, got Rs 5,000 each from 55 of them. Her outstanding including interest shot up to Rs 2,60,000. Ganesan, who complained to the Chennai Police, ratcheted up a combined loan of Rs 4,50,000 from 37 instant loan apps.

Others were careful; they borrowed and repaid on time, i.e. within 6-7 days. But at some stage, they got stuck, and were unable to repay on time. Mumbai-based Prabhu Jeyabalan, 33, began his loan journey in March 2020, and easily paid back eight of them. However, in early December 2020, he was stuck with a Rs 20,000 loan that he needed urgently, but could not repay. According to S. Harinath, ACP (cybercrime), who is posted in Rachakonda (Telangana), the affected people included those whose outstanding was over Rs 3,00,000 each.

Four people arrested in the crackdown on app-based instand credit scam.

What the borrowers didn’t realise were the three tricky parts of the loans. The first was that although the money was easy to get, the borrowing became addictive. The interest rates were so high that they quickly totted up to unmanageable proportions. K. Santosh, 36, who committed suicide, found that the interest on his principal amount of Rs 51,000 was Rs 50,000. K.V. Sunil, 28, too killed himself when his loan of tens of thousands of rupees became a non-payable Rs 2,00,000. The interest meter seemed unstoppable.

Second, many were caught in an initial-cozy, later-shattering debt cycle. As they repaid the loans several times within the stipulated 6-15 days, they felt comfortable. Little did they think that they would fail to do so for extraneous reasons! They were completely unprepared for such a situation. Third was the inevitable debt trap. Borrowers were asked to repay existing loans through fresh ones from other loan apps. This led to a never-ending web of loans. “People were entangled in a vicious circle,” claims Harinath.

Little did the borrowers realise that this was just the beginning of their shocking and nerve-wracking ordeals. Suddenly, as defaulters, they faced a constant barrage of threats, abuses, and blackmail, followed by forged documents from the loan apps’ recovery agents. Outlook accessed screenshots of dozens of WhatsApp texts sent to borrowers. On the last repayment day, a borrower was informed “today is the last due date”. If she didn’t pay up, she would be “charged penalty”, and “you won’t be eligible to take loan again from any NBFC”.

As the app users had shared their mobile data with the lenders, they were shamed in front of their families, colleagues and friends. Jeyabalan’s colleagues received emails that the former was a defaulter and cheater. One day, someone who claimed to be a director in the loan app company, called at 8 pm. He threatened to come to Jeyabalan’s house, and shame him in front of his family and neighbours. In some cases, those who were named as references to the loans were asked to repay the money.

Abusive language by the recovery agents was common and regular. The Telangana-based consultant mentioned above was asked to do whatever it took, even if she had to resort to the world’s oldest profession, to return the money. Abuses in Hindi were a norm. What further scared and scarred the borrowers was a barrage of false documents. These included false legal notices and police complaints against the defaulters. Fake notices came from CIBIL, which maintains every borrower’s credit score. Life became hell.

- Another victim, Rishi Meena, received a ‘Business Action Plan’ from the agents. It listed five steps that the latter took to recover loans:

- All your relatives, all relatives will be called. Dial history hack.

- All relatives’ photographs will be sent to everyone.

- All relatives will be added to one WhatsApp group.

- The photos will be put on the social media site. You will also come to the newspaper on Instagram, on Facebook (sic!).

- A police case will be filed against you. File will be transferred to District Court.

There was no wiggle or wriggle room. If the borrower claimed that her bank’s server was down, the agents provided alternatives—payment through PayTm, RazorPay, or other payment gateways and e-wallets. If someone said that she didn’t have the money, the agents immediately urged her to borrow from another loan app, which happened to be a part of the same fraudster group. Agents would not relent, or cut the voice calls, unless the payments were made. Everything was virtual—through calls, texts, and emails. The lending and payments too were through apps, internet banking, and e-wallets.

Agents of Harassment

A senior police officer in Haryana says the recovery agents had seven ‘bucket lists’ as their ammunition. On the first day of the default, bucket 1 and 2 would kick in, and included reminder text messages and emails for the overdue payments. On the third day, bucket 3 and 4 tactics implied screen shots of contact lists scribbled with ‘420’ or ‘Fraud’. Bucket 5 and 6 meant the creation of a WhatsApp group that included the names from the recipient’s contact list. Bucket 7 was the last resort, as the borrower’s phone and email were flooded with forged documents and abuses.

The whole web, which included thousands of recovery agents, who were based in dozens of call centres spread across the country, and millions of borrowers, was controlled by a dozen or two Chinese nationals based across several countries in Asia. Most of the apps were launched by technology and fintech firms, which were owned by Chinese such as the 27-year-old Zhu Wei (Lambo), who was arrested at the Delhi airport by the Telangana Police. Hong (no full name) was named by the Chennai Police, and gave directions to the Indian managers and call centres through DING Talk, a video-call-based app.

Cyberabad Police commissioner V.C. Sajjanar during a press conference to divulge details on arrests made in the loan scam..

Dandis, another foreigner based in Singapore, operated the various bank accounts to receive loan repayments, and OTPs that generated the loans in the first place. Liang Tian, who was arrested by the Rachakonda Police, and based in India on a dependent visa, married an Indian in 2016. Her husband ran a call centre for several loan companies, and the couple have a three-year-old child. “We are looking for a woman, Yuan, alias Sissi, who too operated out of India,” confides a police officer. Hence, the Chinese largely managed the loan apps, call centres, and money flows.

Of course, they had the Indian partners, who acted as dummy directors in loan app concerns, or owned the call centres that recovered the money from the defaulters. Willingly, or unwittingly, tech giants like Google and Apple helped the loan sharks, as the apps were downloaded through their mobile platforms. If a borrower happened to download one, she received ads from a dozen others with more lucrative loan schemes. Hence, the ad agencies too knew. The RBI did not check that most of these micro-lending apps were not registered with the central bank, as they had to be, and did not disclose their sources of funds, as they were bound to do.

Ironic as it sounds, the RBI was right to assume that many of the loan apps got their funds from legitimate sources like banks and NBFCs. For the latter, it was a win-win situation, as they lent to a few companies, and did away with the hassles to deal with millions of individual borrowers. The loan apps were happy—they borrowed at lower market-linked interest rates, and doubled and trebled them for the final customers, who paid up to 50%. The paralysed central bank, of course, was caught napping, as people suffered.

Queries emailed to RBI, finance ministry, Razorpay and Paytm remained unanswered.

However, the police contend that a large chunk of the money came from illegal sources. Lambo, one of the arrested Chinese, ran an investment apps scam, which was like Ponzi schemes, and offered huge returns to the investors. This money was used to provide loans, which earned huge interest. Another source, says Save Them India Foundation in its petition, was crypto-currency, like Bitcoin, which was earned illegally from gambling and narcotics. The states’ police are sure that funds also came from China, Singapore, and Hong Kong.

Hence, it was tough to either pinpoint the entire sources of funds, as well as their final destinations when the loans were repaid. Hyderabad’s ACP Goel explains, “We are working on the money trail. Initial investigations reveal that funds from NBFCs or apps were credited into bank accounts, and sent through payment gateways to the borrowers. On their return, repayments of loans, they followed different trails. Instead of going back to the NBFCs or apps, the money went through different merchant IDs and accounts.”

Like the loan apps and their funds, the net of the agents, who operated through call centres, was huge. Goel’s team raided six centres in Gurgaon, Hyderabad, and Bangalore employing 2,000 agents. One of the centres in Pune employed 650 people. They used SIM cards procured illegally. “In one of our raids, we found 1,100 SIMs, which were obtained by an Indian firm and supplied to a loan-app one. This violated the norms,” says Chennai Police commissioner Aggarwal.

The recovery agents were young, between 20 and 40, and educated. While most studied until eighth standard, some were graduates. They were hired the usual way people are for the call centres. They were trained to use abusive language and shaming tactics to get the money back. Each morning, they got a target sheet of the defaulters, along with their past performance scores—ability to return the money. Interrogations showed that the agents thought their roles to be similar to those who act on behalf of banks and NBFCs. They had little sense that their actions were illegal, or that they were a party to a loan scandal. How can lenders survive, if people default?

Now, after a dozen suicides, and harassment of thousands of borrowers, have the regulators and investigators woken up from their slumber. The states’ police may now work with the central Enforcement Directorate to recover money, and look at money laundering angles. The RBI set up a committee to define rules for loan apps. Google said it has barred many apps, told app developers that they have to tell the others to follow the laws of the land, ban those who don’t adhere to them in the future, and help the investigations.

Yet, as the debt debris mounts, and the death toll shocks the nation, it is national interest that’s at stake.