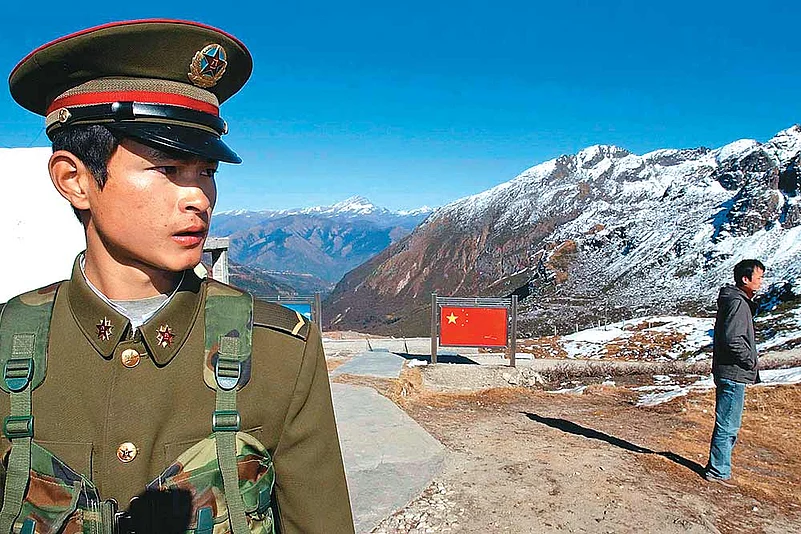

India has had a long history of standoffs with China, given their long and unsettled border. On one occasion it has led to war, on others, skirmishes and artillery duels. But in the past 40 years, the confrontations have been carefully choreographed through a series of Confidence Building Measures to ensure that the two countries do not end up shooting at each other.

What makes the current clash in Doklam plateau serious is its location, and the fact that it is entangled with the issues of a third country, Bhutan. The location is near the Siliguri Corridor, a narrow neck of land, just about 25 km at places, bound by Nepal and Bangladesh and proximate to Bhutan and China.

As distances go, Siliguri, the principal rail, air and road hub that connects Northeast India to the rest of India, is just 8 km from Bangladesh, 40 km from Nepal, 60 km from Bhutan and 150 km from China. With China seeking to expand control over the Doklam plateau, it shortens the distance by 20 kms or so.

Chinese proximity comes through the Chumbi Valley, a sliver of land between Bhutan and India (Sikkim)—the main route of ingress and egress from Tibet to India. What the present face-off is all about is the Chinese effort to add an area of some 40 sq kms or so to the south of the existing trijunction, which India and Bhutan place near Batang La.

From the point of view of treaty, the Chinese have a point. The Anglo-Chinese Convention of 1890 explicitly lays down the start point of the border, and the trijunction, at a place called Mount Gipmochi. But, while India has to accept this as part of the agreement that defines the Sikkim-Tibet border, the Bhutanese don’t, as they were not party to it. So, they have been contesting this and have extended their claim, belatedly though, to the Doklam plateau, a rough area between Gipmochi, a place called Gyemochen which is south of Doka La, and northwards on the ridge to Doka La itself and Batang La.

The issue emerged when the Royal Bhutan Army spotted the Chinese building a road towards their post in the Doklam area. They probably approached the Indians for help and the Indian Army moved across the border at Doka La to block the construction. According to an MEA statement, India and Bhutan had been in close contact on the issue, and in coordination with the Bhutanese, “Indian personnel who were present at the general area Doklam approached the Chinese construction party and urged them to desist from changing the status quo.”

Bhutan has been taking up the issue for years and had been reminding China of the 1998 agreement not to alter the status quo of the China-Bhutan boundary, pending its final resolution. But as is their wont, the Chinese are relentless and follow the tactic which they practice elsewhere—of creating facts on the ground and leaving you with a fait acompli.

The Chinese are hopping mad, because they say that India has violated an accepted border, which is true. But the Indians have done so to prevent the Chinese from bullying the Bhutanese, who lack the capacity to deal with the Chinese. But the Indians have also done it because a deepening of the Chumbi Valley can aid in undermining their otherwise strong defences in Sikkim and the Siliguri corridor.

International treaties are pieces of paper whose value is only set if both the parties have an interest in upholding them. The Chinese have not hesitated to blatantly violate the UN Convention on the Law of the Seas in reclaiming and fortifying rocks and reefs in the South China Sea. So if India perceives that its security is being dangerously undermined, it will act, treaty or no treaty. Even so, New Delhi needs to carefully think if it wants to question the 1890 treaty and reopen the Sikkim-Tibet boundary for negotiation. Beyond that, it must remain prepared to confront the always active PLA.

Given its location, the Siliguri Corridor has long been the focus of military planners and arm-chair strategists. When Bangladesh was East Pakistan, there were concerns about possible consequences of Sino-Pak collusion. To pressure India to ease off on Pakistan in the 1965 war, China built up its forces in the Chumbi Valley and tried to coerce Indian troops deployed on the Sikkim border. In 1967, there were more serious clashes at Nathu La and Cho La, both in Sikkim. With the creation of Bangladesh, the worries have lessened, but not entirely gone.

The job of military men is to construct scenarios and plan to deal with them. Many alternatives can be constructed for military operations in the region. Writing in 2013, Lt Gen (retd) Prakash Katoch said that the Doklam plateau, if occupied by the Chinese, will turn the flanks of Indian defences in Sikkim and endanger the Siliguri corridor. The late Capt. Bharat Verma hypothesised a Chinese special forces attack to seize the Corridor. John Garver cites Indian planners worrying about the Siliguri Corridor being the ‘anvil’ for a PLA hammer coming once again through Bomdi La in Arunachal Pradesh. There are concerns, too, that in the event of hostilities, Chinese forces may just bypass Indian defences overlooking the Chumbi Valley and come through Bhutan.

But Indian vulnerability is much larger. The Siliguri Corridor does not have to worry about just the putative Chinese attack. It is in itself a cauldron of tension, with agitating Gorkhas, Kamtapuri and Bodo separatists, smugglers and transiting militants using it.

For their part, the PLA, too, must be looking at alternate scenarios, especially after their experience with Gen Sundarji and Operation Falcon/Chequerboard. India can use its flanking positions in Sikkim to “pinch out” the Chumbi Valley and emerge astride a Chinese highway going to Lhasa. The Chinese know the Chumbi Valley was the route that Sir Francis Younghusband took in his expedition to Tibet. This attack could well come from northern Sikkim, which is a relatively flat plateau, where Sundarji had once emplaced tanks and Infantry Combat Vehicles in the 1986-87 stand-off with China.

The Chinese worry about the history of the region too. Kalimpong and the erstwhile East Pakistan are where the CIA and Tibetan exiles once planned operations against their forces in Tibet.

Indian and Chinese perceptions of vulnerability are common—the Chinese worry about the Chumbi Valley and Indians are concerned about the Siliguri Corridor. But both have larger calculations and concerns. The Chinese are neurotic about Tibetan separatism and see India as the principal villain, so they adopt a forward policy wherever they can to keep us off balance on this issue.

The Northeast is, of course, intrinsically important to us. But it also has a practical and important military role beyond just the defence of the area. It is where we locate our strategic deterrent viz. long-range nuclear armed missiles, which otherwise lack the range as of now to hit principal Chinese cities.

This is one area with dense military deployments on both sides, the only part of the 4,000 km Sino-Indian border where the armies are close to each other—some 40-50 ft apart in Nathu La and Cho La. In the past decade, India has steadily enhanced its defence capabilities in the East, raising new formations, acquiring heavy-lift helicopters, mountain artillery, as well as forward basing fighter jets. With a new Mountain Strike Corps, headquartered in North Bengal, India has also enhanced the ability of its Army to intervene along the border. But in many ways, it has been playing catch up with the Chinese.

We need to enter a caveat about the chances of all-out war. Of course, it benefits none. The nuclear factor is not something you can ignore. So, the likelihood is that the Chinese will continue their strategy of hybrid warfare, using “Tibetan grazers” to encroach on territory, or building roads without a by-your-leave, creating facts on the ground that become difficult to question. Moreover, Bhutan is vulnerable, because it lacks the ability to challenge the PLA. The main lesson of the present confrontation is the need for a new strategy of dealing with the challenge.

(The writer is a Distinguished Fellow, Observer Research Foundation.)