Covid-19 has brought the entire world to a grinding halt; all activities of progress, growth, development have been stalled. While an effective cure remains elusive, and vaccination proceeds at a glacial pace, the only real resort the world has are the public health measures being implemented across the globe: repeated hand-washing, masking and social distancing. Simple measures, but of course things that have made daily lives a struggle. Caught up in our own frustrations, however, we tend to forget how much more difficult this abnormal phase in the planet’s life is for the young ones. Explaining the various virus containment strategies to them is already an arduous task—enforcing them is taking a real, continuous toll on their mental well-being. The recent Indian guidelines of relaxing mask use for children below five years of age have allowed the young ones to breathe freely. But what about social distancing, and school closure? We have all but resigned to these two states of being, as it were, but they continue to hold our young ones hostage within our very homes. Isn’t it time we think of ways of saving the young generation from the intangible demons unleashed by COVID-19?

Medical literature considers SARS-CoV-2 a predominantly adult infection; chances of children getting infected remain significantly lower than those for adults. In general, children are not the source of infection for their parents; it is usually the parents who infect their children. Even if the children are infected, they suffer mild symptoms. Severe symptoms are seen in children with coexisting medical conditions. Many experts question the role of school closure in containing the virus. Continuous indoor stay with reduced opportunity to go out, and increase in screen time, is the perfect recipe for future myopia (near-sightedness). Not to speak of the risk of chronic diseases like obesity, stress, diabetes, hypertension and cardiac conditions, which are vastly enabled by a sedentary lifestyle, unhealthy caloric intake and lack of physical activity. With this unnatural phase, we are looking at a nightmare future scenario where these are bound to increase in our young population.

So we have physically caged our children with enforced lockdowns, social distancing and school closures. And that’s creating a cascading psychosocial disaster. Opportunities for learning, growing and gaining social skills are being severely thwarted. There are reports that even developmental milestones are getting delayed. A seemingly simple task such as acquiring language needs a whole gamut of stimuli, which includes the hearing of language, the sight of muscle and joint movements producing speech, and the accompanying facial expressions and gestural components. Mere exposure to a screen might not be sufficient to ensure a healthy development of the language faculty. Developing the ability to recognise human emotions in all its myriad nuances needs social interactions; communication skills also need social opportunities. In the crucial phase of infancy, environmental stimulation is essential to make the brain grow structurally to its full potential. It is well-known that limited exposure to appropriate cognitive and social stimuli during vital periods of an infant’s life usually results in delays and deviance in cognitive and social-communication development. Medical research has established that during the SARS epidemic of 2003, Chinese infants experienced a delay in walking, speaking, attaining toilet training, and did not gain age-appropriate weight and height. Only time will reveal the damaging effects our Covid-related social restrictions will have on the generation of ‘pandemic babies’.

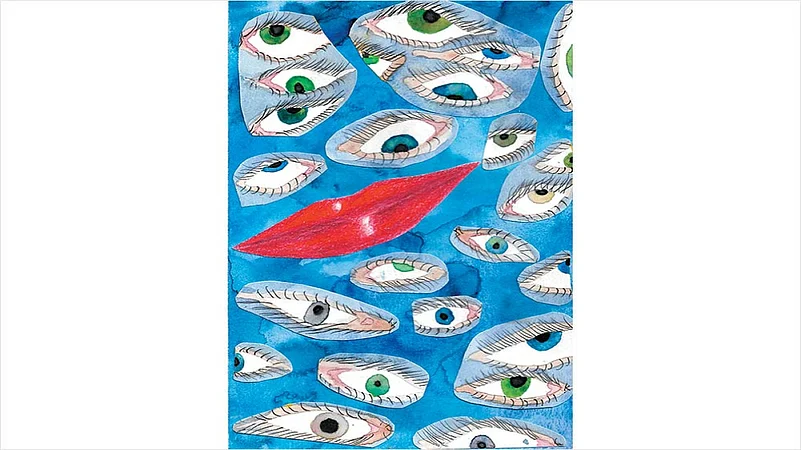

Now, what’s true for cognitive development among babies is extendable, in qualified ways, to adolescents: they are losing vital avenues for growth and development. The adolescents are now earning the name of ‘the lost generation’. Forced social distancing is critically compromising their physical and psychological growth. This crucial period where adolescents already struggle with establishing their identity is a phase of turmoil. Under normal circumstances, this tumultuous phase works as a bedrock for many emotional, psychological and behavioural disorders. Some 50 per cent of all mental disorders appear by adolescence. The future mental health trajectory of the adolescent is determined by environmental factors shaping their gene expressions. Among those factors now, count a pervasive fear of Covid infection, isolation, quarantine, enforced distancing, reduced opportunities for social contact, loneliness. Think of it as a pandemic of insecurity and fear—a hidden psychological pandemic.

The effects are already visible. High levels of psychological stress, anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder are being reported in this vulnerable population. A recent study published in The Lancet Psychiatry from Iceland has documented the ongoing mental health deterioration among adolescents—the study is unique in comparing mental health facts relating to adolescents during the pandemic with the pre-Covid period. The authors found an increase in rates of depression and worsening all-round indices relating to mental well-being among the ‘lost generation’. However, rates of smoking and alcohol intoxication decreased during the pandemic, which naturally owes to reduced socialisation.

Now, decreased socialisation may be proving beneficial for some adolescents; some seem to be able to take this as an opportunity for self-growth. Adolescents report learning new skills, spending precious time with family, and even providing a helping hand in the household. The protective factors of belonging to a secure home with a stable income—which also ensures online learning opportunities—provide a psychological buffer to some well-to-do adolescents. However, restrictions in socialisation are reducing opportunities for adolescents in general to create their self-image, improve their self-esteem, build on peer interactions and communication skills. The skills involved in joining in conversations, holding an argument and conflict resolution need social opportunities. Social solitude is setting the stage for loneliness, stress, anxiety and depression. Those belonging to poor households, whose parents have lost a stable source of income or who were already living in adverse situations with abusive caretakers, have lost the respite that was earlier provided by schools, colleges, playgrounds, teachers and trainers. The second wave has orphaned over 30,000 children across India; the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) collects and maintains the data at a state level. The ‘Bal Swaraj portal’ of the NCPCR collated data in which 2,902 children in the 0-3 years age group, 5,107 in the 4-7 age group and 4,908 in the 14-15 group have lost a parent, are orphaned or abandoned. The NCPCR is working on providing welfare services and facilities for adoption.

Earlier, for vast numbers of children in India, schools used to be the only source of nutritious meals and learning opportunities. The closure of schools and other extended networks has provided the perfect ingredients for toxic stress, adversity, the experience of loss of caretakers, prolonged abuse/neglect, and has even blocked access to social support and child welfare services. How COVID-19 has precipitated an all-round disruption in social structures, and how that’s producing toxic psychological stress for the young ones, needs to be better understood. Being exposed to toxic stress at this tender age disturbs the architecture of the growing brain. Connections between neurons in the brain regions—particularly the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, which are crucial for emotional regulation and memory—are reduced due to the experience of toxic stress. The absence of resilience-promoting factors like environmental support, nurturance by caregivers and the psychological security provided by parents and teachers further increases the risk of developing future mental disorders. Structural changes in the brain and lack of protective factors at a young age can cause depression, substance use, anxiety, obesity, and physical diseases like diabetes and heart diseases later in life. The prevailing circumstances have forced clinicians to provide their services on an online delivery model, with various clinical interventions provided on the e-platform. Tele-helplines are also being functioned to help kids in crisis; an Australian helpline designed for kids reports an escalation of calls during the Covid period. Calls related to infection, mental health concerns, relationship problems and suicidal/self-harm showed an increasing trend. Among the helpline callers, adolescent girls constituted the majority. Emergency psychiatry services are documenting an increase in suicidal behaviour in children and adolescents, raising concerns across the world. A research paper that compiled emergency psychiatry service use across 10 European nations reported a rise in adolescent self-harm behaviour from 50 per cent in 2019 to 57 per cent in 2020. In the Indian set-up, clinical psychiatry services have been badly hit, with only a few specialised centres being able to provide online services.

Psychiatrists and policymakers are joining hands towards creating a framework plan for mental health support during the pandemic. Efforts have been made to provide online guidance to parents, caregivers, service providers, children and adolescents to tide over this crisis. International agencies like WHO and UNESCO have made available parent tips on ensuring a daily schedule, sharing information about Covid-19 with children, how to take care of the self and the kids. Parenting support in graphics, audio-visual aids, comics and e-posters are also available for free access to help parents in home-schooling, and even manage mental health issues in children. The website https://www.covid19parenting.com/audiovisuals offers a big bag of options for parents to help their kids at home. For infants and young children, https://data.unicef.org/topic/early-childhood-development/covid-19/ from UNICEF and https://reachupandlearn.com/package from the University of West Indies contain excellent parent manuals and audio-visual aids to provide stimulating environments at home that can enhance learning for young kids in different age groups.

With adverse household situations, loss of income, not having supportive parents and orphanhood, our children are becoming vulnerable to abuse, neglect, child labour, child marriage and even trafficking. It is for the policymakers to prepare a safety net for protecting our precious future generation from falling into the trap of poverty and deprivation. The welfare services planned by the government of India are a laudable approach; however, much needs to be done to strengthen the support system around the vulnerable child. Provision for mental support needs to be integrated with nutrition, housing, safety and education for children. Only then can we look forward to safeguarding the future of our precious young generation. Otherwise, what we will be giving our children is a form of social orphanhood.

Dr Suravi Patra is Additional Professor, Psychiatry, AIIMS, Bhubaneswar