Ajmal Kasab falls undoubtedly under the now famous ‘rarest of rare cases’ category of murderers who richly deserve to be hanged until death. This one time I am inclined to suppress my abhorrence of capital punishment. National sentiment should perhaps prevail over any other predilection on the subject whenever such mass murders take place.

Having said that, I am not sure how many of my brethren know how wrong a judicial verdict (jury in the case of America) can go sometimes while sending a man or woman to the gallows. The history of criminal justice in the US is replete with instances of those on death row being saved on the eve of their execution by a DNA report that has just reached the state governor or the prison authorities. Such a report more or less conclusively proves that the man in custody is not the murderer or the rapist who has been found guilty by the court. Law in the US provides for a DNA test at the request of a convict, especially where such testing has not been done earlier during the investigation or where the prisoner feels there has been a horrible mistake during the first test. The number of prisoners receiving such reprieve keeps creeping up. According to one recent estimate by the Innocence Project—launched by the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, New York, in 1992, mainly to assist convicts who genuinely feel they have been grievously wronged—there have been as many as 254 prisoners on the death row who were taken off it thanks to the conclusion of a DNA expert that the particular prisoner’s DNA sample does not match the one collected at the scene of the crime or from a victim. Seventy per cent of these belonged to minority groups. The average time spent in prison by those who were released after post-conviction DNA testing was 13 years.

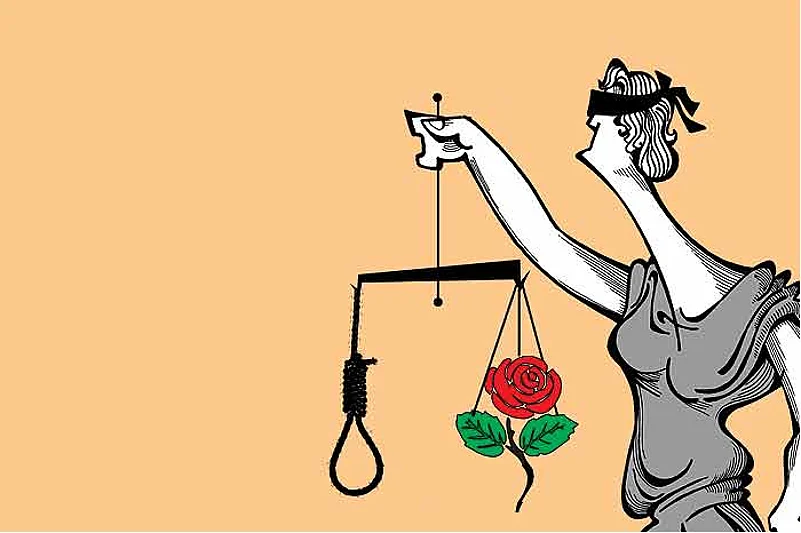

Many who are intensely opposed to the death sentence often cite this phenomenon. After all, is there not an ancient golden principle, which runs something like this: Let several guilty persons escape, but not one innocent be punished for a crime that he did not commit.

My immediate provocation for appealing to those who gloat over judicial executions to reflect on the possibility of a mistake is the case of Raymond Towler, a 52-year-old musician from Ohio who was acquitted by a Cleveland judge on May 5 after he had spent 30 years in prison for the alleged rape of an 11-year-old girl. Judge Eileen Gallagher had no doubt in her mind that the DNA sample put up to her was different from the one picked up from the victim’s undergarment. There was so much emotion in her voice when she told Towler that he was free to go. She didn’t stop with that. She went on to read out a blessing which one normally hears at Irish weddings: “May the road rise to meet you, may the wind be always at your back. May the sun shine warm on your face, may the rain fall softly upon your fields. May God hold you in the palm of his hand, now and forever.”

Can there be a better way to say ‘sorry’ without actually calling out that five-letter word abused ad nauseam by those who are poles away from contrition. The judge did not stop with the blessing. Wiping tears from her eyes, she extended her arm to the prisoner and wished him luck. This was a poignant moment. As for Mr Towler, there was not a trace of bitterness on his visage. When mediamen asked him how he felt, he merely said that a crime had in fact been committed and it took a while for the authorities to sort out who exactly was guilty. Grace and equanimity at their supreme best?

I would like to cite this in all my lectures to IPS officers and judicial officers, if only to prove that in real life, there is nothing like total guilt, and there is always a case for giving the benefit of the doubt to someone who has been arraigned before the law. This is why—many would say—our criminal justice system crawls rather annoyingly. But is there an alternative? Do we want those like Towler to languish in prison for a crime they were wrongly believed to have perpetrated? We definitely need justice that is laced with mercy. Or else we are not fit to call ourselves a civilised nation.

(The writer is a former director of the CBI.)