Frankly I did not see it coming. Nobody from my generation living in a small town of India’s hinterland did. The double-spread advertisement in a film weekly, Screen, should have forewarned us. It was about the launch of the newest kid on the block, Aamir Khan, in Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak in 1988. “Who is Aamir Khan? … Ask the girl next door!” a teaser of its promotional campaign threw a rhetorical riddle at our faces.

I was absolutely clueless despite being the biggest masala movie buff this side of Ganga, Yamuna and Saraswati. So I took the advice literally and asked a young woman from the next block. I was relieved to know that she had no interest whatsoever in a diminutive-looking youngster in black goggles threatening to storm Bollywood. She dismissed him rather disdainfully as another wannabe.

The reason was not far to seek. The young woman was still suffering from the hangover of Vinod Khanna’s return to tinsel town from Rajneeshpuram after the Osho fiasco in the US. Yes, the Khanna with broad shoulders, flowing mane and, of course, John Wayne gait. That was the eighties, folks, and our hero had to look like one! An alpha male with an in-built testosterone turbocharger! Guys like K.C. Bokadia who ruled the industry by churning out endless sagas of guns and gore did not settle for any lesser mortal.

Back then, the leading men of a commercial Hindi film had to be macho with a capital M on screen—a veritable hybrid of an Adonis and a Lothario, with their killer looks and overflowing libido. They were selectively chivalrous and often applied preconditions of a patriarchal set-up when it came to treating their ladylove.

“Aap aise kapdon mein baahar niklengi to seeteeyan nahin toh kya mandir ki ghantiyan bajegi? (What do you expect to hear if you step out in such outfits—whistles or temple bells?)” a sarcastic inspector played by Big B told Zeenat Aman in his deep baritone after she dragged an eve-teaser to the police station. The judge was merely being righteous, not misogynistic, in the Bollywood parlance, mind you!

The social media-enlightened audience would have roasted Amitabh Bachchan today, but we clapped with vicarious pleasure at each of Salim-Javed’s dialogues in Dostana (1980), sexist or otherwise. Some of us whistled too, just like Paintal did in that Raj Khosla film. Our heroes of yore appeared to have landed straight from the pages of Mills & Boon with a compromised complexion—the tall, brown and handsome types, probably with a diploma from the action gurukul of our bald terror, Muddu Babu Shetty (Rohit Shetty’s dad, for the millennials!).

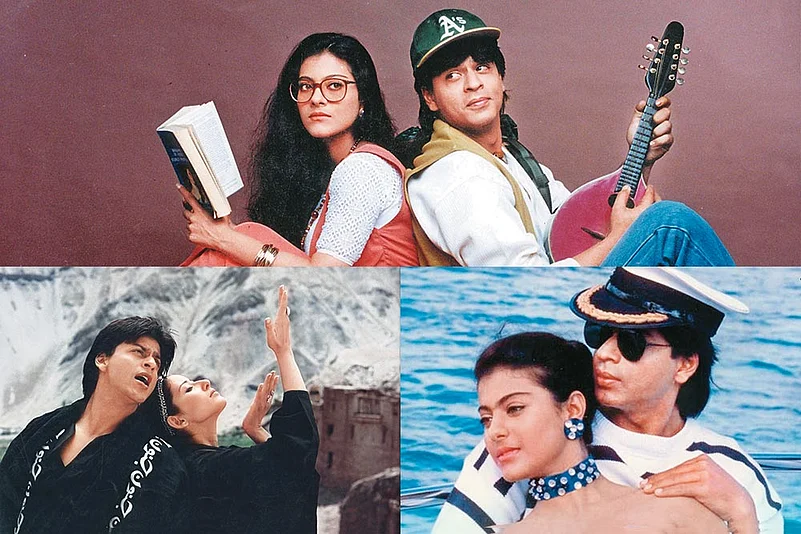

Stills from SRK-starrers (from top) Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (with Kajol), Dil Se (with Manisha Koirala) and Baazigar (with Kajol)

“Bachchan is six-two,” we would exult. Height-wise, 180 cm was the minimum qualification for the leading man in our rulebook. Anybody shorter was not fit enough to adorn the haloed Eastmancolor universe of 70mm as the hero of our favourite action-emotion ka sholaa (embers of action and emotion!). Awful hamming of an actor was acceptable to us so long as the hero looked good enough for a pin-up in the Star & Style fortnightly. Some of the biggest stars of the time primarily owed it to their genes for their prolonged survival in the industry.

But, dear Lord, Aamir was just about five-four or even less. It was okay for Hollywood to fete a Dustin Hoffman or a Dudley Moore, but our heroes had to be tall enough to get our love, adulation and above all, seetees.

The next time I met the same young woman who was infatuated with an actor more than double her age not so long ago, I found her completely smitten with Aamir’s charm. “He is so, so cute in QSQT, naa?” she could barely conceal her glee, switching her loyalties from Khanna to Khan faster than any aaya ram gaya ram from Haryana. She was not alone. Much to my chagrin, I soon found out that Aamir had quietly become the resident teenage heartthrob in our society. Worse still, the acronym, QSQT pissed us off. After all, nobody from my generation had ever committed the sacrilege of referring to Dulhan Wahi Jo Piya Man Bhaye (1977) as DWJPMB. We were puritans, mate!

Still, the most incurable optimist among us thought QSQT’s box office success to be nothing more than a fluke. “It clicked because of its great music by Anand-Milind and a greater promotional campaign by Aamir’s uncle and producer Nasir Hussain,” we would console ourselves.

Obviously, we were still swayed by the swagger and chutzpah of our elderly screen idols who wore unbuttoned silk shirts to show off the tuft of the dyed hair on their chests. They could not have shown anything else without causing immense harm to their image. Very few male actors, therefore, dared to dive into a swimming pool.

Gossip magazines, which were part of our monthly ration, told us with a shshshshsh… that most of them went abroad for a facelift to keep them in circulation. Nobody had heard of botox then. For most actors, it was the era of six pegs (Patiala ones at that!), not six packs. Nobody bothered to hire a fitness trainer, which showed onscreen by default. They had to wear loose shirts and jackets to hide their paunches, a tell-tale sign of their unbroken companionship with Johnnie Walker (not the actor with a similar sounding name!).

Shah Rukh Khan, Aamir Khan, Salman Khan

Aamir’s next few films after QSQT bombed, which brought the “we-told-you-so” smiles back on our faces. Like Kumar Gaurav of Love Story (1981) fame, we thought he would also fade out in due course. The fickle teenyboppers would drop him like a hot potato soon, we imagined.

It all happened because the hero we worshipped was invariably larger than life. He could lock himself up along with a dozen goons in a deserted warehouse and fling away the keys for an invitation to a brawl; a hero who could tell the biggest goon in town not to sit on the chair unless he is asked to because the police station was not his father’s jaagir (fiefdom). He would be extravagant enough to smash a brand new imported Mercedes to give us the Hollywood-like thrill without CGI. We would forever try to ape him, mostly to disastrous effect, but never fought shy of wearing our unabashed love for him on our sleeves.

Oh, how wide off the mark we were! We could not feel the winds of change that had begun to blow across Hindi cinema by the turn of the noughties. The brave, new brigade of young actors did not look remotely like their predecessors, but they took the industry by storm with their talent, confidence and sheer ability to steer clear of hackneyed formulas. They were simple heroes who belonged to our world. Aamir’s success was followed by the advent of two other Khans—Salman and Shah Rukh in quick succession.

Since then, the triumvirate has ruled the industry with more ups than downs, and they are still going strong despite facing new challenges in the pandemic-hit times that have made content a bigger star than anybody with 40 million followers on Instagram.

The nineties truly belonged to the trio who left everyone else behind in the race for stardom with a string of blockbusters. Suddenly, the old guard began to look jaded. Even the relatively younger bunch of stars such as Mithun Chakraborty, Anil Kapoor, Jackie Shroff and Sunny Deol had to cede the ground to them. Only Govinda—forerunner to the young Khans in breaking Bollywood’s stereotypes about the mainstream cinema hero—held his fort for some time with his zany comedies. But he too became irrelevant by the turn of the new millennium.

A makeup artist helps SRK get ready at a film set

Aamir and Salman delivered humongous hits like Maine Pyar Kiya (1989), Dil (1990), Saajan (1991), Hum Aapke Hain Koun! (1994) and Raja Hindustani (1996), but it was Shah Rukh who surged ahead with Darr and Baazigar (both in 1993) and, above all, Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995) that revived and redefined romantic musicals in Hindi cinema in the 1990s.

But then, Aamir and Salman, both Bandra boys, belonged to illustrious film families. Shah Rukh had no godfather as such in the industry unless you count Vivek Vaswani and Colonel Raj Kumar Kapoor. The Delhi boy had done a few Doordarshan serials such as Fauji and Circus (both aired in 1989) before he landed in Mumbai to try his luck in the dream city.

Aamir and Salman had already become big stars by then. Thankfully, Shah Rukh did not have to sleep on an empty stomach on Mahim pavements, as he got good opportunities quite early in his career. Two of his initial hits, Darr and Baazigar, fell in his kitty after Aamir and Salman chose to reject them respectively. Come to think of it, even Arman Kohli had turned down Baazigar.

Shah Rukh soon bought a heritage building (Mannat) at Bandstand, where Anil Kapoor had shot the famous Ek do teen… song of Tezaab (1989) earlier. Today, Mannat, just like Bachchan’s Jalsa in Juhu, has made it to the must-visit wishlist of the multitude of Hindi cinema buffs on a visit to Mumbai.

SRK’s 1990s movies were, of course, not free from Bollywood’s past tropes, like those of his Khan rivals. Nor was he among the best of actors from Hindi cinema. Anybody who has dared to watch Ram Jaane and Guddu (both released in 1995, the year of DDLJ) and a few other ‘gems’ would vouch for that. But he gradually evolved on his own as a widely loved star. Today, mimicry artistes may have made a fortune out of his K-k-k-k-i-r-a-n-n-n, but the 1990s’ audience simply adored him.

With the advent of the multiplex era, SRK emerged as the biggest box office phenomenon. He became so popular abroad that he was hailed as the God of Box Office by distributors operating in the lucrative overseas territory. Much of the credit, of course, should go to the banners of Yash Chopra and Karan Johar, who reposed their unflinching trust in him.

But to give Shah Rukh his due, he never fought shy of taking risks outside their banners, even when he was at the pinnacle of popularity. He not only accepted negative roles in films like Baazigar and Anjaam (1994), but also worked with the likes of Aziz Mirza, Kundan Shah, Ketan Mehta and Mani Ratnam, who refrained from making run-of-the-mill flicks for the box office. The other two Khans were still caught in the crass commercial muddle at the time.

It was primarily his ability and willingness to try out different things that made Shah Rukh such an endearing personality. He had the panache of what the film magazines called a “metrosexual” to pull off a Lux soap ad with the industry’s leading ladies of the past and present as effortlessly as he played a gritty coach of a women’s hockey team in Chak De! India (2007).

All through his career, he has remained the personification of humility and unbridled energy that made him the most loved star of his generation. The whole of India was outraged when he was detained at an US airport.

The middle class—backbone of his support base—has always found his success story quite relatable in the post-liberalisation era. He has always been a common man’s hero, reflecting their dreams and aspirations as well as faults and foibles. It has made Brand SRK one of the longest-lasting in the annals of Indian cinema.

SRK has proved that you don’t have to be larger than life on screen with bulging muscles to win over your audience. You can do that simply by stretching out your arms with a glint in your eyes and a dimpled smile on your face.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Before And After The Khans")

(The writer is a National Award winner for Best Critic on Cinema.)