“There are no innocent bystanders...what are they doing there in the first place?” – Exterminator!, William S. Burroughs

Everything coincided, collided and clashed in that decade. Ram Rath Yatra, Mandal Commission and the rise of the Khans, the trio that would change us, who grew up in the nineties, forever. In the 1990s, the decade that made us who we became eventually, many things happened. Neo-liberalism coincided with the emergence of right-wing politics. The politics was charged with hyper-masculinity.

In 1990, Lalu Prasad Yadav became the chief minister of Bihar. That too happened. I grew up in Bihar. I was in Class 5 in 1990 when it all started.

There was the Ram Rath Yatra that started in the fall of 1990 that L.K. Advani led in a swanky, air-conditioned vehicle to mobilise Hindus to build a Ram temple in Ayodhya. In 1989, the BJP declared their key political agenda was to build the Ram temple on the land where they believed Lord Ram was born. It was the site where the Babri Masjid had stood for over 400 years.

It was also the time when former Prime Minister V.P. Singh decided to implement some of the recommendations of the Mandal Commission and declared before both Houses that Other Backward Classes (OBCs) would get 27 per cent reservation in jobs in Central government services and public sector units.

In September of that year, Rajeev Goswami, a commerce student at Deshbandhu College, Delhi University, attempted self-immolation to protest against V.P. Singh’s decision.

My uncles and cousins were worried. Upper caste men would not have jobs, they said. They paced up and down the hallways. Images of riots were splashed across magazines and newspapers. My older uncles declared they would do kar seva and take their Maruti 800s to Ayodhya and build the temple brick-by-brick. The time, they said, had come to assert their identity.

In 1990, Lalu arrested Advani in Samastipur in Bihar. He had been the chief minister for just seven months. Lalu, everyone at home said, was loyal to the secular brand of politics.

Also in 1990, Aashiqui released. The heroine was tall and dusky. Unusual for the time. There was a scope for love for everyone. Not just the beautiful and the handsome. But then, nothing can be cast in binaries. Neither love, nor politics.

***

We hardly went to theatres because the 1990s in Bihar was also a strange time. They called it “Jungle Raj” and girls stayed mostly indoors after school. At least, we did. We didn’t have cafes we could go to. Cinema halls were too dark for us, given the lawlessness all around. There was a lot we couldn’t do.

A scene from Shah Rukh’s My Name Is Khan in an autorickshaw in Srinagar

Around the mid-’90s, DDLJ released. That’s when Shah Rukh Khan arrived as a lover. Those posters of him holding Kajol in the mustard fields were everywhere. Him playing that violin; him wearing that hat; him just being himself. My father proposed one evening we would all go and watch DDLJ. It was in October 1995. I was in Class 10.

It was in an old theatre called Sapna Talkies in a ramshackle Bihar town called Arrah where my grandfather lived in an old house.

I began to fall in love every now and then after that night in front of the big screen in a small town where the seats were rickety and the sound quality was poor. They even had separate enclosures for men and women and we couldn’t locate our father in the other section. The projector was right in the middle and despite the whirring noise, I heard Shahrukh Khan say, Tum apni zindagi ek aise ladke ke saath guzar dogi jisko tum jaanti nahin ho, mili nahin ho, jo tumhari liye bilkul ajnabi hai.

That was my rebellion. It still is. I didn’t want to be Simran. I wanted to be Raj.

Shah Rukh Khan said he sold love and that’s better than all the pitches selling religion. That was a time when love’s resurgence became an obsession. I still have those chunky shoes and the Polo shirt that were found in every fashion street in every small town. He wore them in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai. He was, after all, the poster boy of liberalisation.

It almost became a ritual. We watched Shah Rukh only on the big screen despite the lawlessness around. My father liked Shah Rukh. My mother adored him. My friend said he has those Jesus arms.

***

Shah Rukh Khan has said, “I am just an employee of the Shah Rukh Khan myth.” We became buyers of the myth. Better than buying other myths/mythologies. He also called himself a peddler of love. Love is all we need. Now, more than ever.

I guess it was he who told us to rebel, to run away and then to return to our roots. In our compressed lives then, he made it possible to dream. He was an outsider. He made it. He gave us hope. His characters and his own story made life bearable in that limited world of ours.

Posters of movie stars on sale at a Chennai pavement

In the Maruti 800 that my father drove, we played the songs from this film. Over and over again. We conjured a lover like Shah Rukh. We even thought we’d become him. He was fluid. He was magical. He was so like us. He was our escape.

On the rooftop where my cousin smoked at night, she would tell me about her lovers. I suspect she was looking for that lover who could count the stars with her, ask her why she sliced her wrists and why she needed so much love. She never found her Shah Rukh. We had been indulged by him. We demanded equal rights at home. We also demanded love in the world. An equal kind of love.

The hyper masculinity of our times had been challenged by this man who made vulnerability so fashionable. He had dimpled cheeks. For many years, I kept poking my cheeks to get those dimples. My grandmother said they are lucky for love. We desperately wanted to love, to be loved.

***

So, in that decade love clashed with everything else. They always say love will win in the end. I chose love. Just as he did in his films.

Now, we live in times where love is threatened. Love Jihad hadn’t been coined then. Nobody stopped us when we fell in love with the three Khans. I bought their posters. We didn’t think of borders then. I stuck his next to George Michael’s poster.

Everything is contextual.

The 1990s was a decade of rebellious fashion, feather cut hairstyles and new and old tailors had set up shop and promised to copy every bizarre outfit we saw on the screen. It was that decade of imagination. We had those old telephones that screeched. VCRs were a status symbol. In a place where kidnappings and killings were a norm, cinema theatres were these little islands where we could sit and hope for miracles. Like love.

Women stand at the back at a cinema show in a village

When I watched Darr in 1993 in a cinema hall, I remembered wanting to tell Shah Rukh Khan to stop pursuing Juhi Chawla. The psychotic protagonist was not my favourite. Years later, I was stalked. I thought of the film and felt very angry.

There are characters and there is the man himself. He reinvented himself. He still sold the idea of love. But he also started to stand against hate. My Name is Khan was a statement.

***

They tell me stream of consciousness writing is not the best way to put things out there. But our thoughts, memories and notions of justice and everything else are never linear. Incoherence is a safe space. Judgement is self-conscious. I have never been for structuralist positioning.

When I see Shah Rukh Khan, I see love. And I see a lot of him now. There is this endless trolling of a star, who is also a father. Love is never without context. Never without its own tryst with history and culture and politics.

We have an uncomfortable relation with the rich and the famous. There is so much ‘othering’ that it is almost a trend now, a necessity too. Everyone pontificates. Parenting lessons, abuse of wealth, this and that. They are also intrigued about what happens in the lives of stars who live in places that are off limits. Stars are spotted in their airport looks, on their salon visits, etc. We like to take a position on everything. Lately, those positions are colour coded.

I was warned against this cover package on Shah Rukh Khan. It could get ugly, a friend warned. You are a woman, he added. But love trumps everything. That’s another idea of India.

***

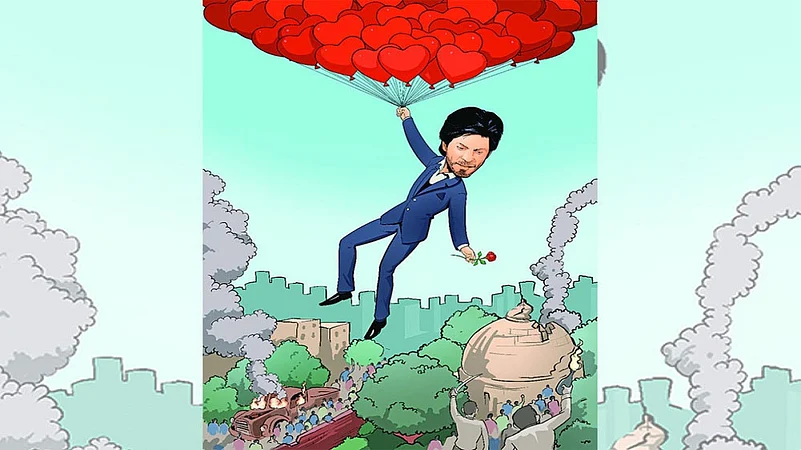

I was in Patna in my grandmother’s room last week where the blue light streamed in through the stained glass window and the wail of a dog pierced through the night. I dreamt of a man floating in the air, holding a string from which a thousand balloons sprung like heart-shaped flowers. They say dreams are a manifestation of the subconscious, which absorbs the news. There is a lot of it. Opinions, updates, poems even on a young man arrested. In cafes and family WhatsApp groups, everyone is discussing bad parenting. In fact, there were stories in the news media on those lines. Like the tale of two fathers. The other one being Union MoS Ajay Mishra, whose son is the prime accused in Lakhimpur Kheri violence case where eight people were killed during a protest against farm laws on October 3. They spoke about concerted cultivation approach to parenting and empathised intensive parenting.

The man in my dreams floated above the broken and the bruised buildings and the brown river that is sacred otherwise, but is a reservoir of bodies, limbs, carcasses. He floated above the mosques and the temples and over that old church where Mother Mary wears saris now. He floated above the hundreds of mirrors they sell on the roadside where people look at themselves everyday and continue to be in denial of their polarised selves. And he floated past those flyovers and that bridge on the Ganges that goes nowhere but rises out of the water as pikes on which rests an unfinished promise. He held a rose as an offering. Perhaps to the river that has been stabbed with all the promise of development.

The red heart-shaped balloons, the stars, the night sky and the man who held out a rose. A white rose. There was a bright green building. It wasn’t all orange. I woke up. It was Shah Rukh Khan.

I dare to dream. I am a writer. So, I will write. Despite the politics. In spite of the trolling. Personal is political. Always.

(This appeared in the print edition as "That ’90s Love")