In my darkest teary-eyed moments, I have turned to the films and words of Shah Rukh Khan. And as I learned through the past decade, I am hardly alone. Shah Rukh appears as recourse in many teary-eyed moments triggered by the drudgery and loneliness of being an Indian woman who seeks affection and achievement on her own terms. From the drawing rooms of Jor Bagh to the forests of Jharkhand, across diverse classes and communities, I have spent fifteen years chronicling how female fans curled up with Shah Rukh when they found the real world and its pandemics and patriarchy inhospitable—a tapestry of encounters that fortified my love for the star.

When the women featured in my book felt unloved by society because they chose to love themselves or their jobs, Khan offered smiles and delight. Most importantly, for women without access to organised movements or feminist thought, he has supplied language to critique unfair relationships with men and families. “Why can’t these men be more like Shah Rukh? I do not mean about money and style but the way he speaks to women and about our problems,” a home-based agarbatti-maker told me in Ahmedabad. As mawkish as it may seem, I simply cannot divorce him from the love and comfort he has provided to so many women of my generation. But why do these women turn to Shah Rukh in their most desperate moments? What does he represent?

It feels impossible to write anything original about an icon as self-aware and intelligent as Shah Rukh Khan. Through nearly three decades of films and media interactions, the man has consistently displayed a remarkable grasp of his own cult. The actor often describes himself as “an employee of the myth of Shah Rukh Khan”. At a 2017 TED Talk, he drew an amusing parallel between the journey of humanity and his own journey as an ageing film star. In a light-hearted display of vulnerability, characteristic of his public persona, he said: “Before this talk, I decided to take a good, hard look in the mirror. And I realised that I’m beginning to look more and more like the wax statue of me at Madame Tussaud’s. In that moment of realisation, I asked…do I need to fix my face?”

I tear up a bit as I write this, because it must take unimaginable bravery for an icon celebrated for his youthful romances to acknowledge age on his face. That too, amidst a roomful of strangers. Then, I laugh. Because I’ve heard many Shah Rukh detractors repeat the exact same criticism about him, of how he has become a caricature of himself, how he is too old to play the lovelorn hero. Do they learn their insults from the self-deprecating things Mr Khan says about himself? Or is Mr Khan acutely aware of how people see him? I suspect it is the latter. So, it is tough to say anything new here. Because no one seems to interrogate their own icon with as much scrutiny as Mr Khan himself.

However, many brave men and women have attempted fascinating books and articles on the star. Since 1992, I have read various pieces aimed at decoding his remarkable career. Much more so in the past few weeks. To counter the hate unleashed by a small-hearted circus that seems to delight in targeting a Muslim icon, there has been an outpouring of love for the actor. Watching the episode unfold with horror and helplessness, several artists, activists, journalists and ordinary people have come out to stand with Shah Rukh. They write beautiful op-eds, poems and posts; fan clubs put up posters outside his home and curate videos of heartwarming messages to support Khan through his ordeal. Many of the voices standing in support of Khan have been female. This is unsurprising as Khan has left an indelible imprint on the intimate lives of various women in South Asia.

Each fangirl I interviewed, irrespective of her education or wealth, pointed to the way Khan looked at women. In his films, I was told, the leading man pays whole-hearted attention to the woman he claims to love. Khan can conjure up a gaze of romantic devotion unlike any other human on celluloid. With all his romantic might, he gazes at the magnificence of his lover, his eyes tearful with joy and spiritual satisfaction. Shah Rukh’s gaze is soppy and ridiculous to the rational sensibility, but female fans do not care. Because that look is not one of condescension, not where a woman is seen as a troublesome burden or an object of lust, a silent, uncomplaining outlet for male carnality. Even when he plays it cool, churlish or attacks female dignity, Khan’s characters spare a moment in the song sequences to unleash that trademark gaze. He looks at his lovers with a remarkable register of adulation and admiration, a spiritual and bodily embrace each fan I spoke to desperately wanted in her real life.

Worker-fangirls from India’s low-income precariat highlighted Khan’s ability to demonstrate love through concrete actions. These women taught me to see Khan very differently. Each of his films holds a pivotal psychological moment when a deeply flawed male places a woman—her worldview, her needs, her politics—above his narrow self-interest. In film after film, you will see him sacrifice his ice cream (Kabhi Haan Kabhi Naa), his job (Yes Boss), his prestige (Deewana), the patriarch’s approval (Pardes), his chance of easily getting the girl (Kabhi Haan Kabhi Naa) and even his life (Dil Se). Khan’s intense portrayal of steadfast commitment to the woman he loves eclipses the toxic elements of his filmography. The female fans I spoke to fully acknowledged the triggering aspects of many of his films—the stalking and negging, Raj harasses Simran and refuses to elope, and Amarkant forcibly kisses his love interest. Yet, they chose to celebrate the love Shah Rukh offered women in his filmography.

Khan’s interviews have also allowed him to rise above the men he essays. In a conversation with Simi Garewal, the actor said, “I think I have a lot of woman in me.” Female fans from elite and upper-middle class homes obsessively followed Shah Rukh’s interviews. They had memorised his witty university lectures and myriad thoughtful comments. English-speaking fans could recite multiple media interactions where Khan had talked about how hard the work of womanhood was in India. An engineer fangirl offered: “Even if it is an act, I appreciate it. Who else is talking about women like this? Our culture is full of men who don’t really like women who are outside the home. They seem scared of us or can only objectify or patronise us. Shah Rukh likes women. That’s why he is different.”

Popular media commentary tends to project Khan as one of the Great Men of India’s liberalisation story. These narratives adhere to a traditional framework of writing and thinking about India through the great stories of Great Men. Shah Rukh is cast as a tall icon: his greatness is seen as a feat of extraordinary individual achievement measured by the money he makes, the awards he receives, the box-office magic he has created, the number of brands he endorses, the number of his fans and followers. The stories about Khan’s icon also succumb to another strand in the Great Man framework. In this high-minded view of the world, Great Events are shaped by Great Men; and Great Men are nurtured by Great Events. In the case of Khan, economic liberalisation, the growing clout of South Asian immigrants in the West and the telecom revolution are always cited as key propellants for his persona. Concomitantly, the rise of the religious right is understood to hurt the power of his star. Recently, observers have opined on his dipping box-office fortunes in New India. Liberalisation’s poster child finds himself struggling, much like the Indian economy.

A large share of writing on Khan is usually done by those steeped in the business of film and journalism, those with some access to the star and the Bollywood eco-system. There will be fun insider anecdotes on how films were made, parties that were hosted and roles that were lost. Paragraphs will be spent on the box-office fortunes of various cinematic efforts. The books and articles will also make several references to Shah Rukh being a post-liberalisation superstar, his middle-class Muslim heritage and his embrace of progressive secular values. Authors will call him a Nehruvian hero, discussing his comments on religious intolerance. Some will fume over his political silences. Others will eat omlettes with Khan, provoking my envy. There will be commentary on his role as South Asia’s romantic superhero, some grumbling about the religiosity and gender-politics of his soppy family dramas; and much consternation on certain toxic aspects of his filmography. Amidst this writing, there will always be the deepest admiration for how he made it on his own, without any venerable lineage.

A film icon is no individual star. Rather, an icon is a constellation formed by multiple stars—audiences, technology, socio-political circumstances, co-actors, journalists, musicians, writers and directors. And yet, when we read about the story of Shah Rukh and the constellation of events that launched him into the hearts of millions, the fangirl appears as a mere footnote. The fanboy got a full film. While the actor always lovingly acknowledges his female fanbase, the writing on his icon will usually feature bemused anecdotes about bored sexless housewives, fans who outlandishly emulate him, or those who claim to be his mother. Other than a few remarkable pieces, the writer rarely seems like the kind of person who would giggle uncontrollably at an image of Khan or take pleasure in joining Khan’s public birthday bash at ‘Mannat’. Foreign fan-clubs are of interest, to demonstrate the global nature of Shah Rukh’s appeal. But the lives of ordinary Indian fans do not feature extensively in the analysis of Khan’s extraordinary career. Fangirls, in particular, are deemed too ubiquitous and banal for investigation: they are understood as being uncomplicated love-addled spectators to a Great Man’s adventures, especially in a country with a penchant for deifying male public figures. “They love him,” we are told, as if this love is blind devotion for a deity, without the lover and her gaze holding any agency or power of her own. Fandom—the act of unambiguously adoring an artist—is understood as mere escapism and foolish uncritical worship, not a set of actions that are nourished by our socio-economic realities.

SRK’s fanbase among women transcends the rural and urban divide

I attended Shah Rukh’s birthday bash outside ‘Mannat’ in 2019, the last time such an encounter was possible before the pandemic. During the five hours I spent in a small corner, I counted at least a hundred male and merely ten female pilgrims. There were many more fans sprawled along the ocean promenade. The crowd felt overwhelmingly male. Most female fans were accompanied by men, but I did spot and speak to three women who had arrived solo. Excited and afraid, each recalled cases of women being molested and injured by a mob of men at the Mannat birthday celebration in 2017. They were acutely worried about the stalker cult surrounding Shah Rukh, fearful that some of the fanboys took their cues from Shah Rukh’s portrayals of obsessive lovers who tormented women. The solo female fans knew the risks they faced, weighed the pros and cons, and decided to participate anyway. Fandom had triumphed over fear.

Thousands of fans of all faiths had gathered, many chanted for Shah Rukh. Bharat ki Shaan, Shah Rukh Khan. India’s Pride, Shah Rukh Khan. Perhaps secularism still stands a chance outside Shah Rukh’s home on Bandstand. Several male fans had saved money for a year to travel and buy custom-made T-shirts for the occasion—a luxury very few female fans I followed could afford. “It is not only about money. If I go for a holiday to see Shah Rukh, who will cook for the home?” a home-based garment worker from Uttar Pradesh once said to me.

Each time the gates to ‘Mannat’ opened, these men would surge towards the house, unleashing a tidal wave of masculine energy. As the largely male mob pushed forward, the women ducked for cover. They were either swept aside or swallowed up in the crush. The solo female attendees I interviewed survived the scene, spotted their star and said they would be back next year. They would continue seeking Shah Rukh on his birthday, despite the perils of being pushed around by hundreds of men. Why are these women willing to bear discomfort and danger to simply wave at Shah Rukh from afar? What love does his icon provide?

When I asked female fans why they loved Shah Rukh, a common set of answers emerged across class backgrounds: he does the housework in the films; he listens to women and acknowledges their experiences and feelings; he is comfortable being vulnerable. By portraying men who find strength in expressing emotions and their hunger for love, Khan redefined masculinity in popular culture. The love Shah Rukh’s characters seek is not only the traditional love of a woman, but they also desperately seek the love and approval of fathers, friends and fellow countrymen. The men he plays feel deeply, are constantly vulnerable to the gaze of the Other and shed many, many (many) tears. Measuring talk time, Shah Rukh’s films allow more dialogue for women. The ladies in his films are accorded an interior life—they are not victims or badass heroines; they daydream, journal and write poetry.

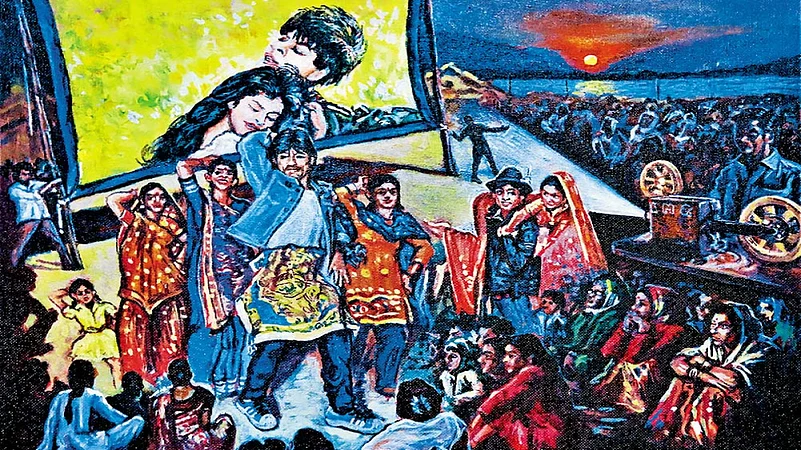

Posters of some of SRK’s biggest hits.

While visions of Shah Rukh might serve as mere escapism in the plush homes of Lodhi Road, indulging in fandom becomes a form of assertion, even protest, amongst poor and working-class women. Watching a film with your own money, for your own pleasure, independent of the family, is seen as a woman flexing her economic muscle. In 2017, six out of ten audience members at an Indian cinema hall were men. By catering to a massive female fanbase with his portrayal of a loving vulnerable man, Shah Rukh has always served the fantasies of a minority group at the movies. A national survey in 2015 found that only eight per cent of adult women reported visiting a cinema hall at least once a month, while twenty-one per cent of men reported making a monthly visit to a cinema hall. Men also have greater exposure to mobile phones and OTT content. Limited access to media devices or independent incomes, no free time for fun, unfriendly public spaces and rising ticket prices conspire to restrict the number of women who can enjoy cinema. Men have more money and freedom to pay for the content they want to see.

Sadly, being a fangirl is also dangerous business in many homes in India. Through their repeated expressions of fandom, often embarrassing for parents or husbands, some of the women I followed for the book deviated too far from the boundaries of female propriety. Acknowledging fandom meant that a woman was clearly acknowledging that she had a body and that it had desires. I suspect the taboo on female sexuality is the reason why many women framed their fandom for Shah Rukh as being rooted in an appreciation of his hard work and his manners. Some part of their love for the actor was anchored in sex and sexuality—they liked his body, they thought he was handsome, they wouldn’t mind waking up next to him.

Women in the villages of UP and the slums of Delhi are chastised for watching Shah Rukh on TV or singing his songs. Personal phones and televisions are destroyed. And yet, I’ve witnessed working-class women part with hard-earned wages to cruise Khan’s images in the face of censure from their families for what they considered wasteful spending. Many faced violent hostility for merely watching a film without seeking permission from their parents. When I asked these women why they persisted with such costly fandom, their answer was simple: “We love Shah Rukh, to hell with what our families think.”

Once, at a media conclave, I occupied a cheap seat and watched a well-intentioned Delhi heiress ask Shah Rukh why he did not use the power of his iconic status to make movies which “changed the way people think”. This idea, that mass masala or romance films, don’t provoke introspection or thought because they do not conform to Western aesthetic codes or aren’t gritty depictions of ‘issues’, is just straight-up condescending and inaccurate. Through watching Shah Rukh and his fan-women, I’ve seen how his films and celebrity—despite flirtations with toxicity and tradition—bolster many ordinary women’s appetite for love. These women give Shah Rukh’s songs and films a good long think. They use his scenes to think about their own lives as well. I have witnessed Shah Rukh stir women’s imaginations. A posh banker from a posh school pointed out how “his characters always performed emotional labour in a world of asshole withholding men”. Another fan, a Santhali domestic worker from Jharkhand, was enthralled by how his character Surinder Sahni in Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi serenades his wife and celebrates the tiffin she makes for him. She said, “If men in real life appreciated the kitchen work women do like he does, women’s lives would be much better.” In response to the heiress, Shah Rukh said that cinema existed for many reasons, one of them being to help audiences and actors escape their realities.

A twenty-four-year-old Muslim fan from Bapunagar in Ahmedabad had moved to Mumbai to work for a survey firm in mid-2019. In early 2020, she made her only reference to religion in our ten years talking about Khan. The young woman expressed disappointment at Khan’s silence on the violence following the NRC-CAA protests. But it took her two minutes to add, “Maybe he is doing something and not in the open. Maybe it is a tough time for a Muslim hero to speak.” A fangirl’s impossible fantasy reveals her reality. This young woman’s fantasy of Shah Rukh unequivocally supporting the NRC protests reflects her lived experience of a public culture that does not express unambiguous solidarity with Muslim youth. As real people disappointed, she placed her expectations on Shah Rukh.

In fantasising about Khan, female fans tackled their oppressive realities. Because none of us know Shah Rukh. We made him up and he happily participated in the myth we had created. In imagining Shah Rukh, the women I encountered tried to imagine an alternative to the masculine worlds they occupied. They forged, out of the gossamer fabric of their hopes and dreams, a man who would support freedom and choice for women—whether to work, rest or watch movies. This imaginary world, with its teary-eyed men who wholeheartedly love women with wide open arms, may not be radical, but it is a challenge to the world we currently occupy, in which so many women feel unappreciated, unsafe and unloved.

At a time when the public sphere encourages us to remain divided by identity and reside in spiritual silos, Shah Rukh reminds us of the unifying potential of love. In our era of cynical actions and censored thoughts, lofty romantic notions are radical. The greatness of Khan does not reside in his public political statements, his box-office collections or brands. Nor does it lie in his youth, muscles or beauty. He is past all that. As filmmaker and writer Nasreen Munni Kabir said to me, “He is like the Beatles. They had good songs and they had bad songs. But the Beatles will always be the Beatles. And Shah Rukh will always be Shah Rukh. Nothing can touch that.”

It is not great events and current affairs that sustain his appeal. Nor is it his individual greatness. As magnificent and hardworking as the man is, his power draws from the good faith and fantasies that countless people, across religions and classes, have reposed in him. And as long as our culture continues to punish women for pursuing pleasure, recognition and reciprocity in relationships, Shah Rukh will endure as a shining alternative to the strangulating masculinity that surrounds us. To borrow a phrase from a celebrated journalist, Shah Rukh is Teflon coated by love.

(This appeared in the print edition as "The Power Is In The Looking")

(Views expressed are personal)

Shrayana Bhattacharya is trained in development economics at Delhi University and the Harvard Kennedy School. Her book Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh: India’s Lonely Young Women and the Search for Intimacy and Independence is releasing in November 2021.