Cinema is a medium grounded in technology. If we look at the history of cinema, changes in technology have always influenced its aesthetics and how they are made. Satyajit Ray was a very practical, hands-on man, to whom technology was merely a tool to tell his stories. He was firm in his beliefs and values. But he was always flexible regarding the mode of work or use of equipment.

As is quite well-known, he was adept at innovation and improvisation. Right from the early days, when he was shooting his first film, the team he had got together was made up of people with no previous hands-on experience in cinema, except for his editor. In fact, Subrata Mitra, who later became one of the leading cinematographers internationally, had never handled a movie camera before, even though he was an accomplished still photographer. There is an anecdote that he had asked Ray how he could entrust him with a responsibility in which he had no experience. Ray had replied that since Mitra knew the basics of photography, he could acquire the skills of capturing moving images along the way. All of them learnt skills while working.

ALSO READ: The ‘Normal’ Lens

When, for various reasons, he decided he wanted more control over film-making resources, not only in direction, but also in editing, composing and recording music, mixing the soundtrack etc, he took the trouble to learn the technology. He was never overawed by it. To him, it was just a means of achieving the end he had set for himself.

I have seen during the re-recording of Pratidwandi and other films that he used to be in the sound studio and, despite there being renowned sound technicians like Mangesh Desai in charge, Ray would handle one or two of the sound-faders. In editing, when the technology changed, a lot of editors in Calcutta felt a little apprehensive about moving to the new one. But he just absorbed it, learnt it as he went, and so did his technicians. My assumption is that he would have made the transition from analogue to digital seamlessly.

ALSO READ: Ray Of Hope

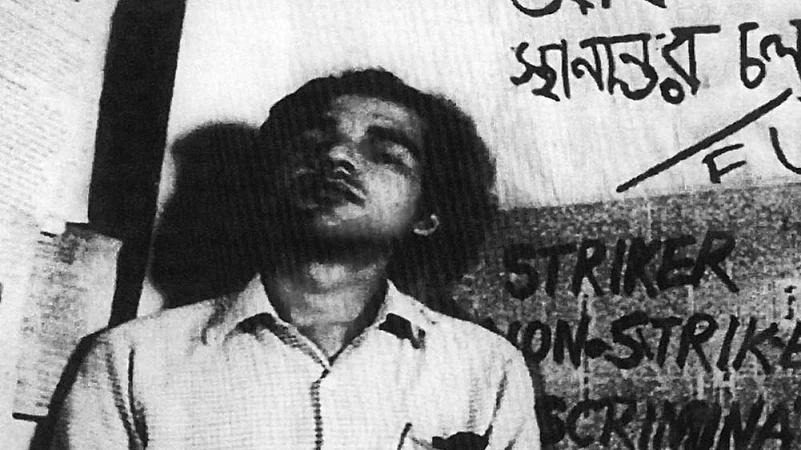

A still from Aguntuk

However, he would not have done it merely to go with the trend. If we look at his use of colour, he had used it quite early in his career, in Kanchenjungha. He felt the particular subject needed colour. Then he switched back to black and white. He again went back to colour at a later stage. He chose the format he thought his subject demanded. Another example is the use of the zoom lens. When the zoom lens first came in, a lot of people were so excited that they often overused it. Ray, too, was excited about this new technology, but used it sparingly and appropriately.

We should keep in mind that he made most of his films in the environment of the Bengali film industry. That means he had to work on fairly limited budgets. He never had the luxury of huge budgets. Therefore, his choices were also determined by the budget. During shooting on location, he would move out after the day’s shooting, wander around with a tape recorder on his shoulder, and record various sounds that he would use later.

ALSO READ: Most Wanted

I remember that some of the dubbing for Pratidwandi, for various reasons, had to be done without looking at the picture. So, he devised a way. He wrote down the dialogue that had been spoken, marking all the pauses and punctuations, and underlining places where there should be an emphasis. That gave him a dub track that would be easier to sync later. His innovations were always dictated by practical need.

Coming to new media such as OTT, I don’t have a single answer to the question of what he would have done. Apart from one film, Sadgati, which he made for Doordarshan, he did very little work for television. So, whether he would have embraced or welcomed OTT remains an open question. But I’m pretty certain he wouldn’t have let new technology deter him.

ALSO READ: The Unerring Casting Eye

From what I have seen, one of the problems film-makers have faced while shifting from analog to digital, and then OTT, is the phenomenon of moving from a live audience in front of a large screen to individual viewers on smaller screens, such as laptops and mobile phones. That demands a fundamental aesthetic change in the way the audience sees something. On the large screen, you notice depth of field and greater resolution than you do on small screen. These are basic aesthetic differences. A lot of traditional film-makers sometimes seem a little troubled by that. I am sure these issues would have concerned him as well. But I have a feeling he would have found a way around them. He would have reconciled himself to the arrival of this new platform, adapted and carried on in his own way.

We can talk about how he viewed the medium in a larger context. There used to be a kind of divide between parallel cinema and mainstream cinema. Each had their own audience. Parallel cinema had a more socially and politically conscious audience, made up of people who knew the grammar of cinema to a certain extent. Ray was, of course, conscious of these differences. Once, we were having a conversation when I asked him about the concept of rasika. In classical music, rasika is a person who knows the grammar of music and can appreciate music at a deeper level. I had asked him if he thought the concept applied to films too. He replied there would always be two kinds of audiences—rasikas, and those who would see, enjoy and assess films at a surface level. He said he tried to make his films work at more than one level, to satisfy both audiences.

ALSO READ: Uncle Auteur

Coming back to the question of the fast-changing technological environment, there is no denying internet has penetrated fairly deep into our lives. I have seen watchmen in housing societies watching movies on their mobile phones to pass time. Ray wouldn’t have had any problem with this personal kind of viewing. I remember when the Sony Walkman arrived in the market, and someone gifted him one, he was very excited about the new ‘personal’ experience. Internet platforms would have certainly helped him reach a larger audience.

When we were growing up, getting access to foreign films was very difficult. One had to wait for film festivals or depend on film society screenings. Now, courtesy platforms like Netflix, anybody and everybody has access to films made in Iran, Thailand, Eastern Europe…wherever. A lot of walls and boundaries are breaking down.

ALSO READ: The Household On Bishop Lefroy Road

I think if he were alive today, he would have seriously considered making films on Professor Shonku. He would have grabbed the opportunity. The character was very close to his heart. In one sense, Shonku is almost a reflection of Ray. Shonku is internationally famous, but refuses to take up residence at a university abroad. He prefers to work by himself, out of his little house on the banks of the Ushri. In his personal life, Ray was as much a Bengali as he was a man of the world. Shonku may be called his alter ego. Besides, the Shonku stories are not culture-specific. You do not need to be a Bengali to understand and appreciate them. In comparison, Feluda, the detective, is culture-specific to a certain extent. The Shonku stories are all set in an international context. They have foreign characters and are located in various parts of the world. Ray could have roped in foreign producers and taken the Shonku series to an international audience. He would have, most definitely.

(As told to Snigdhendu Bhattacharya) (Views expressed are personal.)

Dhritiman Chaterji is an actor who began his career as the protagonist of Ray’s Pratidwandi