A writer who is both me and is not me, when he is asked what his book is about, says that the question he is asking is the following one: who among your neighbours will look the other way when a figure of authority comes to your door and puts a boot in your face.

I’m talking about what happens in the first few pages of my recently-published book, A Time Outside This Time. The question that our narrator poses above might make you think of a book like George Orwell’s 1984, but I was thinking of examples closer to hand. I had seen a video of a man named Qasim who was lynched by a mob in Hapur, Uttar Pradesh, in 2018. In the video, Qasim is sitting in a dry canal beside a field. He has been assaulted by cow vigilantes. We cannot know this from looking at Qasim, but his ribs and knees have suffered fractures; there are contusions on his body, wounds made with screw-drivers and sickles, and there are fatal injuries on his private parts.

In the video, we can see the onlookers. Qasim asks for water, but no one responds, and he falls over in the dirt, as if settling for sleep in his bed, one knee folded atop another. For the narrator of my novel, the question that arises is similar to the one he asked earlier—what can you write that will make anyone reading you give a dying man a drink of water?

The world comes to us in the form of bad news. Apart from writing fiction about the news, I have used newspapers as my painting surface, using gouache to alter or transform what I had first encountered only as news. When the pandemic arrived in America, I painted on the obituaries printed in the New York Times. From India, even earlier, there were reports of lynchings and rape. I asked my sister in Patna to mail me both Hindi and English newspapers, and then I set to work in an effort to regain a small measure of sanity.

I’m not alone in doing this, of course. For a recently-unveiled virtual museum, As If A Girl Matters, artists and writers have responded to a crime that took place in Kathua, Kashmir, in 2018. The facts are gruesome and well-known. Eight-year-old Asifa Bano was gang-raped and murdered in a temple. She belonged to a nomadic Muslim tribe of shepherds and was grazing horses on public land when she was kidnapped. Her abductors wanted to drive away from the area the tribe to which Asifa belonged. The details of the case are terrifying even to read and it is particularly intolerable to imagine a child’s body being turned into a battleground.

More than a hundred visual artists, dancers, writers and musicians, as a way of paying tribute to Asifa’s life, have donated work to the virtual museum. Here is a tiny sample: Arpita Singh maps a geography on canvas where the names Kathua and Unnao are repeated; Nilima Sheikh presents a tableaux of a girl turning into a woman in ‘When Champa Grew Up’; Gauri Gill’s black and white photograph from 1999 portrays a shepherd girl and her goat in the desert in Rajasthan. There are several wonderful dance and mixed-media pieces: for example, Mallika Sarabhai’s uninhibited, graceful performance of Maya Angelou’s ‘Still I Rise’; a video of dancers from Raw by Nature depicting the racist violence of police killings in the US; the slow and gentle choreography of the late Astad Deboo alone in a room or Melissa Wu’s brilliant presentations of bodies in dance in New York’s gritty urban spaces. The writing curated on the website shows a similarly wide range. From Kiran Desai’s eight haikus that invoke the presence of an eight-year-old girl called Asifa to an essay by Anuradha Roy focused on the day the news broke; from a poem by Meena Alexander dedicated to Nirbhaya to a piece by Deepti Priya Mehrotra from which one learns that Indian courts heard 64,138 child rape cases in 2016 alone.

Sumri, daughter of Ismail the shepherd, Barmer, from the series ‘Notes from the Desert’, 1999-ongoing. Copyright: Gauri Gill

The contributions to As If A Girl Matters cover a wide range, a generous mix of established names as well as those less well-known. For my own contribution to the museum, I sent a painting I had done in the days immediately after learning about Asifa. I had imagined the temple steps and I called the painting ‘Haadsaa’, which I translated in my mind as “a tragic happening”. For this painting, I had used a sheet from a newspaper sent by my sister from Patna. Then, a few days later, I did another painting. On this page of a Hindi newspaper, there was a report about girls playing Holi, and, by sheer luck, also a photograph of the great writer Mahadevi Verma. I titled this painting ‘Ladkiyan Hain, Khelne Do’, which, again, I translated as “It is Spring: Girls Want to Play”. And because the torture that Asifa endured was also a result of her being a Muslim, I also included a painting I had made of a lynching.

As the months passed and I continued to work on the novel I was writing, I kept thinking of Asifa. One particular turn in that entire perverse drama appeared as a particular challenge to me. The savagery of the perpetrators was plain enough, but what I couldn’t understand was the fact that a protest march by a newly-formed group had been organised to defend the accused. Why? According to the newspaper report I read, the organiser of the march was a high-ranking political leader. If a crime as heinous as this still found defenders, then perhaps it was useless for my novel’s narrator to believe in presenting the truth. For it was clear that truth didn’t necessarily change people’s minds. Facts would be twisted to confirm people’s biases and their deepest prejudices. We were dealing not just with bad news; our real problem was bad faith.

How are we so blinded by hate? I have a suspicion that some people think our dislike of one community or another is ingrained in us, that it runs so deep and so pure that it is almost natural if not also mythical. But this would be false. There is good reason to argue that at least as far as communal differences in India are concerned, colonial rule by the British played an instrumental role. Partition is a long, bloody gash in our collective memory. Estimates about the number of those who died ranges from 200,000 to two million. In what might be the largest migration in history, between 10 million and 20 million people were displaced.

‘Ladkiyan Hain, Khelne Do’ by Amitava Kumar

But even Partition didn’t come out of nowhere, British historian Alex von Tunzlemann told me. She said, “Colonial rule was itself physically violent and helped to create a society in which violence was normalised: this was why Gandhian non-violence was so radical. Pairing this violence with a policy of ‘divide and rule’—which was especially visible after the census began in 1870s—had serious consequences.” Consider the art-work that the late Zarina Hashmi contributed to the As If A Girl Matters museum: a wavering line, thick and black, arbitrarily drawn into a geography that is otherwise continuous. It is as if a powerful, invisible hand created a rift, and imposed on a whole land an ideology of difference. Hashmi’s art is a potent reminder that the horror of Partition lives on. The dividing line that cut across Asifa’s life is, as Hashmi might have put it, now the atlas of our world.

While recognising the explanation that history provides, there’s another side of me that isn’t satisfied with simply blaming the British. I cannot but echo the questions asked long ago by the filmmaker Khwaja Ahmad Abbas: “Did the English whisper in your ear that you may chop off the head of whichever Hindu you find, or that you must plunge a knife in the stomach of whichever Muslim you find? Did the English also educate us into the art of committing atrocities on women of other religions right in the marketplace? Did they teach us to tattoo Pakistan and Jai Hind on the breasts and secret organs of women?”

Studying history may provide context, von Tunzelmann told me, but it does not provide excuses. What it means, I believe, is that we take responsibility. It is striking to me that the hate-mongers in our society, conducting their dog-whistle politics, make their mark on the public stage by repeating what the colonisers did successfully—setting communities at each other’s throat and stripping us of any sense of unity. So obscene is their passion that those who dissent are thrown into jail, while those who call for riots are rewarded.

‘Haadsaa’ by Amitava Kumar

On its website, As If A Girl Matters museum expresses a desire to express our common humanity. For me, this begins with an ethic of hospitality, with the idea of making the other, who is a stranger, feel welcome in your home. I often think of a poem by Palestinian-American poet Naomi Shihab Nye, which begins thus: “The Arabs used to say / When a stranger appears at your door / feed him for three days / before asking who he is, / where’s he from / where he’s headed. / That way he’ll have strength enough to answer. / Or by then you’ll be / such good friends / you don’t care.” Or, if that is too much, can we at least be more hospitable to our laws and allow them to fully enter our lives?

During two years and more that followed Asifa’s murder, I continued to work on my novel. The book ends with a meditation on the life left in a man being killed. I was imagining the death of Mohammed Akhlaq—and also George Floyd. We live in a world where the media often parrots the propaganda produced by the powerful. In such a world, novels can function as a democratic platform: made of many characters, and presenting a plurality of viewpoints, novels can inaugurate a public sphere that is often absent in real life. Or perhaps I’m presenting too grand a view of my aspirations as a writer. The plain fact is that I wrote a novel to keep a small precious truth alive, a truth about the times we are living in. “Write the truest sentence that you know,” Ernest Hemingway said, and that is what we must do as a daily task. Remember Asifa and others like her so that the human inside us also stays alive.

(This appeared in the print edition as "As If A Girl Matters")

(Views are personal)

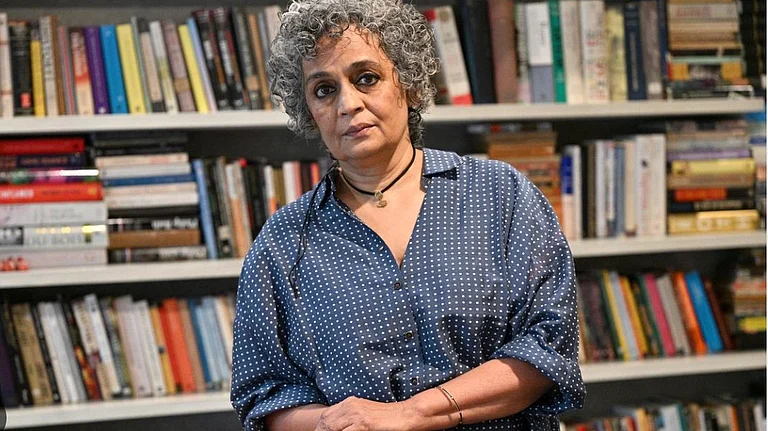

Amitava Kumar is an author, most recently, of the novel A Time Outside This Time. Born and raised in Bihar, he now teaches English at Vassar College, New York.