Satyajit Ray was born on May 2, 1921 to a family of extraordinary talent. His grandfather Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury was a legendary children’s author, painter and musician. Upendrakishore’s eldest brother Saradaranjan Ray was an eminent academician and was known as “W.G. Grace of Bengal” for his role in popularising cricket in the province (and his WG-esque flowing beard). Youngest brother Kuladaranjan was the first to translate Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Jules Verne into Bengali.

Satyajit Ray’s father Sukumar was perhaps the greatest Bengali children’s author ever, his poems and tales of whimsy and fantasy quite unmatched in the annals of Indian literature. Several of Satyajit’s aunts and woman cousins were literary luminaries. Upendrakishore, Sukumar and Satyajit are possibly the largest selling Bengali children’s authors of all time. There is hardly a Bengali child who can read the script whose first books do not include Upendraishore’s fairy tales, who doesn’t then graduate to Sukumar and subsequently to Satyajit’s stories of the eerie, the supernatural, the dignity of the meek, detective Feluda and scientist Professor Shonku.

ALSO READ: Ray Of Hope

Sukumar passed away when he was only 35, with Satyajit two years old. The young Satyajit—or Manik (gem)—seems to have been a solitary child, though adored by his uncles, aunts and elder cousins. But an aspect of Satyajit that has rarely, if ever, been noticed, is that in all the stories he wrote—whether for print or films—there is not a single child (and his stories and films very often featured children) who is not an only child; none of them have siblings. And all of them are marked by a lively curiosity and active imagination. This can only be explained by Satyajit’s own childhood experiences.

When he was seven, Manik travelled with his mother to Shantiniketan and met Rabindranath Tagore, who had been a close friend of both his grandfather and father. In the boy’s autograph book, Tagore wrote an eight-line poem—now quite familiar to Bengalis, though few may be aware of the Satyajit connection. “Let him keep this. When he’s a little older, he’ll understand it,” Tagore told Manik’s mother. The poem says Tagore had travelled the world at great expense and seen every country, the greatest mountains and the vastest oceans, but he had failed to see the world outside his own door: a single drop of dew on a stalk of rice—“a drop that reflects in its convexity the whole universe around it,” as Ray later commented. This thought would form the essence of Ray’s cinematic thinking—the sighting of the universal in the smallest of objects or gestures, or simply the play of light and shadow.

ALSO READ: Message In The Medium

“What is wrong with Indian films?”

Ray told his biographer Marie Seton (Portrait of a Director) that he spent hours as a little boy investigating the mysteries of light. “There was an intriguing hole in the street door of his uncle’s house. Manik would stand in front of this with a piece of broken frosted glass in his hand to catch the reflection of people moving outside on the street. The shaft of light coming through the hole worked like a box camera. Years later, he told his photographer friend A. Huq that the images impressed him more when there were sounds with the images. Thus, he was dimly aware of audio-visual effects at a very early age.”

Sukumar had wanted his son to study at Tagore’s university. Satyajit, however, had grown up, by his own admission, largely on a diet of light English fiction, and uninterested in Indian art and literature. But after graduating from college, he bowed to his mother’s wish and enrolled in Kala Bhavan in Shantiniketan for a four-year course in art. He quit after two and a half years, because he “just felt that I had learnt all that was there to learn”, but his time at Shantiniketan and class trips to the great art centres of India like Ajanta, Ellora and Konark would have a deep influence on him. “At last I was beginning to find myself and my roots.”

ALSO READ: Most Wanted

He got a job at the advertising agency D.J. Keymer, where he met D.K. Gupta, a manager there who had launched the publishing venture Signet Press. Apart from his day job, Satyajit started doing cover designs and illustrations for Signet’s books. Today, we can safely divide the history of Indian book design into two phases—pre-Ray and post-Ray. Renouncing the clean formality of British cover design and illustrations, Satyajit practically invented book design as an art form in India.

Meanwhile, his interest in cinema was deepening. Along with friends, in 1947, he set up the Calcutta Film Society. Two turning points in his cinematic journey were approaching—Jean Renoir’s visit to Calcutta to shoot The River, and his four-and-half-month stint in London in 1950, where he watched 99 films (he kept a list), including Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves.

ALSO READ: The Unerring Casting Eye

“What is wrong with Indian films?” is the title of Ray’s first published article on cinema, in The Statesman in 1948. “The raw material of cinema is life itself,” he wrote. “It is incredible that a country that has inspired so much painting and music and poetry should fail to move the filmmaker. He has only to keep his eyes open, and his ears. Let him do so.” Two years later, in London, Bicycle Thieves, which he watched more than a dozen times, would be a revelation: cinema could represent life in all its nobility and nuances, turn the ephemeral into the eternal, and find startling truths in the apparently irrelevant. And all this did not depend on budgets or quality of equipment.

Bicycle Thieves seemed to validate what he had been thinking and what he had gleaned from Renoir. Through his filmmaking career, Ray would adhere to some tenets that he had learnt from Renoir. For instance, “You don’t have to have too many elements in a film, but whatever you do, must be the right elements, the expressive elements.” And “one quality to be found in a great work of cinema is the revelation of large truths through small details.” (This is an echo of Tagore’s little poem.)

ALSO READ: Uncle Auteur

All this also heightened Ray’s frustration with Indian films. In a March 1952 article, he wrote: “In the 30 years of its existence, the Bengali film on a whole has not progressed one step towards maturity.… There is no director in Bengal whose work even momentarily suggests a total grasp of the film medium in its dramatic, plastic and literary aspects.”

Things were about to change. Ray had written the screenplay of Pather Panchali (The Song of the Road, 1955), which would be his first film, on the ship home from Britain two years ago.

ALSO READ: The Household On Bishop Lefroy Road

Apu’s Revolution

It is difficult to imagine today how revolutionary Pather Panchali was as an Indian film. Wrote Sham Lal, legendary editor of The Times of India, in his paper (under the pen-name Adib), after watching it in a morning show in Bombay: “It is absurd to compare it with any other Indian picture—for even the best of the pictures produced so far have been cluttered with clichés. Pather Panchali is pure cinema.… (Ray) composes his shots with a virtuosity he shares with only a few directors in the entire history of cinema… The secret of his power lies in the facility with which he penetrates beneath the skin of his characters, and fixes what is in their mind and in their hearts—in the look of the eyes, the trembling of the fingers, the shadows that descend on their faces.”

For director Adoor Gopalakrishnan, writing in 1998, “(Pather Panchali marked) the beginning of the true Indian cinema—a beginning for all of us. It was not only a total negation of the soulless and superficial all-India cinema indifferent to real people and issues, but also an affirmation of the emergence of the first consummate artist on the subcontinent’s motion picture scene. So, for all of us…in the beginning there was…Pather Panchali.”

The film was contracted to run for six weeks in a Calcutta theatre chain. It was taken off when the contractual period ended, even though it was running to full houses, because the chain had been booked months ago to release renowned South Indian producer-director S.S. Vasan’s Insaaniyat, starring Dilip Kumar and Dev Anand. The day after Pather Panchali was taken off, Ray was woken up by an early-morning visitor. It was Vasan. Vasan told Ray that he had watched Pather Panchali the night before and “If I had known that this was the film Insaaniyat was going to replace, I would have certainly withheld its release. You have made a great film, sir.”

It may seem rather strange that Martin Scorcese, a director apparently near-antipodal to Ray in style and choice of topic, led the campaign for an honorary Oscar for Ray, which he received in 1992. But is it really so? Scorcese recalled: “I was 18 or 19 years old (when I watched Pather Panchali for the first time) and had grown up in a very parochial society of Italian-Americans, and yet I was deeply moved by what Ray showed of people so far from my experience. I was moved by how their society and their way of life echoed the same chords in all of us.” And it can be argued that Scorcese’s “uncharacteristic” films like The Age of Innocence and Hugo carry Ray’s influence, with access to a level of funds and technology that Ray could not have dreamed of.

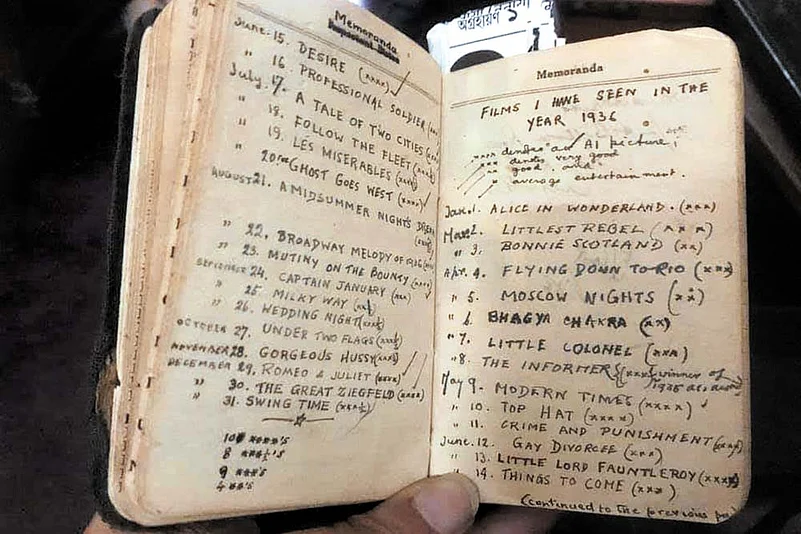

From the 15-year-old Satyajit Ray’s diaries, listing films he had watched in 1935 and 1936—mainly Hollywood films—with “star ratings” given to each.

The World of Bengal

“My films are all concerned with the new versus the old,” Ray once explained. They can also be seen as a history of Bengal—and India—through carefully crafted snapshots. Jalsaghar (The Music Room, 1958) looks at the crumbling feudal order, as a cash-strapped zamindar plans a last great musical soiree to establish his superiority over his nouveau riche neighbour. In Devi (The Goddess, 1960), a powerful condemnation of religious superstition, a zamindar has a dream that convinces him that his daughter-in-law is an incarnation of Durga, leading to terrible consequences. In Kanchenjungha (1962), an arrogant brown sahib is given a lesson in humility when he realises that his writ no longer runs in newly awakened India.

Mahanagar (The Big City, 1963) charts the rise of the Indian woman, as Arati takes on bread-earner responsibility for her family after her husband loses his job. Ashani Sanket (Distant Thunder, 1973), set during the Bengal famine of 1943, examines how blindly accepted social structures like caste disintegrate in the face of hunger.

Apu, born in a small village in an indigent Brahmin family, is tied down by economic and social circumstances, which however cannot tether his mind or spirit. In Pather Panchali, he is the curious child soaking in the life around him—a life stained by tragedies over which no one has any control. In Aparajito (The Unvanquished, 1956), his ambition to be a part of the wider world collides with his mother’s desire and need to keep her beloved son close to her—an issue that teenagers have faced across the world and from time immemorial.

In the final film of the trilogy, Apur Sansar (The World of Apu, 1959), we see the achingly beautiful love story of Apu and his wife Aparna, are devastated at Aparna’s death in childbirth, and want to cheer with abandon when Apu, who had spent years blaming his son Kajal for Aparna’s death, walks into the sunset (technically, sunrise) with little Kajal on his shoulders. As a work of pure humane communication that rises above linguistic, racial, geographical barriers, the Apu trilogy is unlikely to be surpassed.

But do the young men in the films Ray made in the 1970s on contemporary themes—after long being accused of “living in an ivory tower”—represent Apu-figures in a different time and context?

In Pratidwandi (The Adversary, 1970), the sensitive and imaginative Siddhartha (just as Apu was) hunts for a job, and feels increasingly impotent in a teetering world of clashing attitudes and ideologies. Ashim in the underrated Aranyer Dinratri (Days and Nights in the Forest, 1970) and Shyamalendu in Seemabaddha (Company Limited, 1971) are possibly what Siddhartha would have become if he did not speak his mind in job interviews. They are successful executives. But Ashim wonders whether the more he rises, the more he actually falls. And Shyamalendu jettisons all his principles in his fight for a seat on his company’s board.

The man who sinks to the most squalid depths is Somnath in Jana Aranya (The Middleman, 1975). Unable to find a job, he enters the dark world of “order supply” and can clinch a lucrative order only if he supplies the decision-maker with a woman. He ends up sending his best friend’s sister into the businessman’s hotel room. The Middleman was released at the height of the Emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi, when all the dreams of independent India seemed to have been shattered. Somnath’s father, who had believed in the dreams, is a confused, poignant and anachronistic figure.

The Middleman also marks the beginning of a dark phase in Ray’s cinema that would last till the end of his life. Till The Middleman, Ray’s films had the distinctive quality of not passing judgement on people. His most famous quote, after all, is “Villains bore me.” As Amartya Sen wrote, “In Ray’s films, villains are remarkably rare, almost absent. When terrible things happen, there may be nobody clearly responsible. And even when someone is clearly responsible, as Dayamoyee’s father-in-law most definitely is responsible for her predicament, and ultimately for her suicide in Devi, he too is a victim, and by no means devoid of humane features… Ray chooses to convey something of the complexity of social situations that makes such tragedies hard to avoid, rather than to supply easy explanations in the greed, the cupidity and the cruelty of ‘bad’ people.”

But this empathetic humanism would eventually disappear from Ray’s films.

The Women

Satyajit Ray believed women were brighter than men. He told biographer Andrew Robinson (The Inner Eye) that he thought so because women found themselves to be physically weaker than men, and developed an intelligence and perceptual abilities keener than men. And the sensitivity that Ray brought to his portrayal of women characters is rare.

Charulata (1964) was Ray’s personal favourite among all his films. While Madhabi Mukherjee is magnificent as Charu, her performance is illuminated every moment she is on screen by Ray’s camera, which seems to know the tiniest changes in her thoughts and moods as reflected in her face. Men cannot help but fall in love with her.

Karuna in Kapurush (The Coward, 1965) is far more courageous and knows her mind far better than her lover Amitabha, the “coward” of the film’s title. In Nayak (The Hero, 1966) and Seemabaddha, the women played by Sharmila Tagore are the voice of honesty and inalienable values. But the two most interesting women characters in Ray’s world are Arati in Mahanagar and Aparna in Aranyer Dinratri. Circumstances force Arati to go out into the world and earn, working as a door-to-door salesperson. Initially diffident, she grows in confidence and moors her family with a calm resolve. She quits her job over racially motivated injustice done to an Anglo-Indian colleague. A paean to womanhood, Mahanagar is certainly one of Ray’s best films.

If Arati represents the strength of the female force, Aparna is the feminine mystique. “I can’t figure you out,” Ashim tells her. “Is that necessary?” she asks. Later, she tells Ashim: “When I saw you for the first time, I thought it would be fun to shake this man’s confidence.” “You have shaken it,” he admits. “You haven’t experienced any great sorrow in your life, have you?” asks Aparna. As a child, she has seen her mother burning to death, she has endured her brother’s suicide; she is more compassionate, insightful and centred than the materially successful Ashim, whose persona is ultimately fragile. The film ends with Ashim deeply in love with her, but she promises him nothing. Ashim, who has been accustomed to getting whatever he wanted, must grow to be worthy of her.

Crisis in Civilisation

The last decade of Ray’s life (he passed away in 1992) sees an angrier and increasingly bitter creator. The man who had had contempt for stereotypes and dogma (“I commit myself to human beings, and that is good enough for me”) seems to vanish. The films become wordy and didactic, and yes, there are villains.

Ghare Baire (The Home and the World, 1984) is a visual feast, with its marvellous period sets, brilliant cinematography and use of colours. Yet the characters lack depth. Soumitra Chatterjee is made to play Sandip as a straightforward bad guy, with his eyes expressionless except for the occasional sinister gleam. One can almost see a dark cloud of Ray’s disapproval hanging over his head every time he appears on screen. And the man who made Charulata fails to evoke much sympathy for the principal woman character Bimala.

This was followed by Ganashatru (Enemy of the People, 1989) based on a Henrik Ibsen play. Here, Ray attacks religious fundamentalism, certainly a just cause, but again, one can spot the villains from a mile away, and they have no redeeming qualities. The set designs are reminiscent of 1970s Doordarshan plays, the lighting flat and the camera never moves an inch.

Shakha Prashakha (Branches of a Tree, 1990) suffers from the same atrophy. The worn-out trope of the brain-damaged innocent as the voice of conscience is trotted out. The issue this time is growing dishonesty in society, though for Ray, this seems to begin and end at, one, all businessmen are corrupt, and two, one should not avoid paying income tax. Dialogues like “It’s difficult to find a genuine human being in today’s world” jar to the bone. And, incredibly enough, while the central figure (the “tree” of the title) is a paragon of honesty who has built a thriving township around mica mining, no one seems to have informed Ray that mining of mica had been banned by the Indian government a decade ago.

We will never know how much of the poor quality of these films is due to Ray’s ill-health—he had two heart attacks in the early 1980s and never recovered fully.

Thankfully, Ray’s last film, Agantuk (The Stranger, 1991), released a few months before his death, is not an embarrassment, though it remains cinematically slipshod (a Santhal dance, shot so mellifluously in Aranyer Dinratri, is filmed now with staggering lack of imagination and camera movement). In Agantuk, Ray questions the very concept of civilisation as we know it. His alter ego, played by Utpal Dutt, avers that the so-called primitive tribes were far more civilised than we are. A safari-suited villain is supplied, with distressingly cliched arguments. The lifelong humanist appears to have lost faith in humanity.

Yet, Agantuk does touch some chords. And a hilarious scene with an elderly deaf lawyer is wonderful assurance that Ray had not lost his acute sense of humour, absent from his films for more than a decade.

The film inevitably invites association with “Crisis in Civilisation ”, the last essay that Tagore wrote, two months before his passing in 1941, as he confronted the horrors of the Second World War and what he saw as a decline in Indian values. “As I look around, I see the crumbling ruins of a proud civilisation strewn like a vast heap of futility,” he wrote. It was a cry of anguish and despair. But in the very next sentence, he says: “And yet, I will not commit the grievous sin of losing faith in Man.” Agantuk, too, ends on an optimistic note, as the “stranger’s” suspicious relatives redeem themselves and the little boy vows never to be “a frog in the well”.

So how does one really evaluate Satyajit Ray? Perhaps Pauline Kael, arguably the finest film critic of the 20th century, said it for all of us: “Ray’s films can give rise to a more complex feeling of happiness in me than the work of any other director.” That is infinitely more than most artists can achieve, or even hope to achieve. That, in itself, is enough.

(Views are personal.)

Sandipan Deb former Managing Editor of Outlook, was Editor of Financial Express, and Founder-Editor of Open and Outlook Money magazines.