It was not till the 1960s that there was a large-scale revolution in urban middle-class taste. Government intervened through a network of organisations (Handloom House, Handloom & Handicrafts Corporation, Weaver's Service centres, Cottage Industries, National Institute of Design etc) and Indira Gandhi's imprimatur was felt everywhere. Prime minister for 12 years, she was keen on design and marshalled taste-makers of the order of Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, Pupul Jayakar, Charles Correa, Ahmedabad's Sarabhai family and their cultural inheritors such as Martand Singh and Rajeev Sethi. Indian arts, crafts and textiles were wheeled out at trade fairs abroad and foreign designers were honoured guests at home. Up-to-date India was doffing its cap at international design, dictated from above.

Block-printed curtains went up in 1970s drawing rooms, rough Bhagalpur silk-covered sofas, family carpets were chucked for chattais from Bastar and Madhubani paintings replaced respectfully garlanded family portraits. Colonial India vanished in a puff of smoke. Village India was the new chic, often taken to desperately comic extremes, with south Indian urlis and Shekhawati cradles turned into coffee tables and Gujarati grain cupboards dressed up as bars. The ethnic vocabulary was further garbled by sudden intrusions of double-speak in cities like Delhi and Mumbai.

Patwant Singh, who ran Design magazine in Delhi, put a Charles Eames chair in his drawing room, weaver Monika Correa installed a functioning handloom in hers, and Minnie Boga in Delhi and Vina Mody (wife of the late MP Piloo Mody) ran successful furnishing shops in Delhi and Mumbai where "ethnic chic" and 1970s modernism lived in conjugal bliss. One result of this union was a line of straight-lined furniture with seats and backrests in woven charpai string. Middle-class mothers such as mine were in full cry. Plastic in any form—Formica tabletops, pseudo-Scandinavian furniture and lamps and Melmoware dinner plate—was their dream. But it didn't last long—like the Moradabad vases and Melmoware soon became extinct.

Louis Quinze meets the Orient: A living-room set-up in a Mumbai residence, 2000

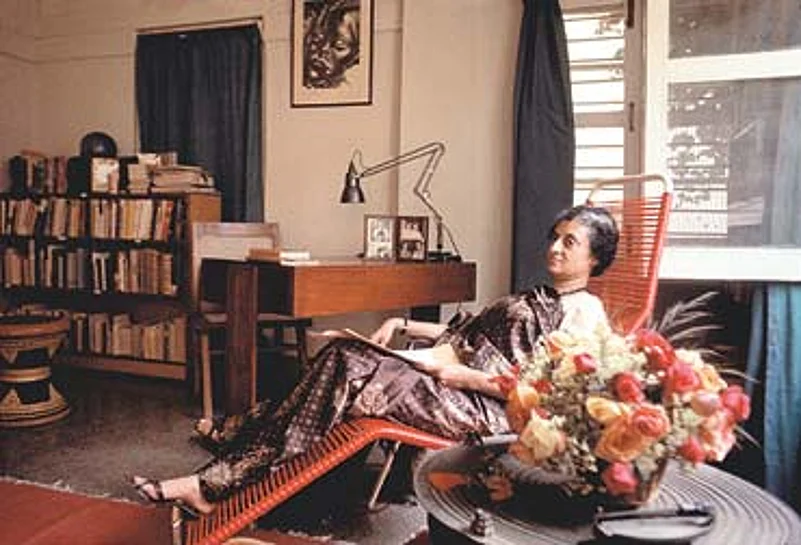

The traces were visible well into the 1980s. For a perfectly preserved full-blown example, retained like a fly trapped in amber, you can stroll past Indira Gandhi's personal interiors, encased behind glass at 1, Safdarjung Road. It's a national treasure as memsahib's memorabilia: modernism, ethic terracotta, books, antiquity and discreetly hidden works by Husain or Gujral are combined with effortless ease. It's apparently comfy and low key. In fact, it's an artful, but not effortless, blend of an Indo-European intellectual's interior.

I recall a much-quoted bon mot about exactly such a style. In the 1990s, Gautam Bhatia, the architect and satirist who coined the phrases "Punjabi Baroque" and "Bania Gothic" to describe the new urban living styles, walked into the flat of Malvika Singh, publisher of the intellectual magazine Seminar, surveyed the room, cocked an eyebrow and announced, "Early Pupul Jayakar?"

Every generation acquires the worst faults of its age, so it can be assumed that the drawing rooms we hate the most are our parents'. Deconstructing the notion isn't difficult: they are too near to our own perceived faults, so we prefer something two generations removed as delightfully antique, therefore, pleasing. My loathing for Moradabad brass and pseudo-Scandinavian furniture persists but, when my mother died some years ago, I rather fancied her father's Edwardian whatnots and Meiji Restoration porcelain. My parents, on the other hand, may have thought them worth nothing but a good kick. Nowadays, the drawing room with the most swagger is where period Husains, Souzas and Anjolie Menons jostle with installation art by some newly discovered genius.

Gypsy queen Livleen Sharma’s drawing room in Delhi, 2007

Some years ago, when I was researching my book Indian Interiors, my editors looked through hundreds of Indian locations and homes—metropolitan, urban and rural—from Dimple Kapadia's lush drawing room in Mumbai to the blue-washed town houses of Jodhpur. But there was one interior that we were unanimous about including from the outset: Gandhi's ascetic room at the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad. It is small, light-filled and airy and virtually a cell. There is nothing to it: a gadda and charkha, a munshi-style desk, a calendar, a clock and some books. It's minimalism in its purest form: natural, functional and devoid of all decoration.

In the prevailing mantra of minimalist style that haunts Indian drawing rooms, Indians have, as usual, misunderstood the origin and development of the concept that the West took, adapted and redefined from the East. It has nothing to do with cunning lighting or 80-inch TV sets and digital surround sound. It has to do with the final simplicities of life: of paring down one's drawing room to an empty void.