The really surprising thing about the Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar Samajik Parivartan Sthal aka ‘Mayanagari’ in Lucknow is not its extravagance but its understated elegance. On the banks of the Gomti river, stretching from the whimsically mannered La Martiniere School to the ersatz colonial Taj Residency, ‘Mayanagari’, spread over 123 acres, is a majestic sight. Constructed entirely with pink sandstone and red Agra stone, the site (with some exceptions like two rows of squat, white elephants) romances the Lucknow light quite lyrically. Indeed, one could be forgiven into imagining one were in Mesopotamia or Nalanda or Fatehpur Sikri. I exaggerate, but only a little.

Not since the days of Shah Jahan has something been attempted on this scale in India. Early British architecture, like the Residency in Lucknow, have a tentative, almost sorry-for-intruding, grace about them. The later, more assertive buildings of the 20th century, like the Victoria Memorial or the Rashtrapati Bhavan, have a grandeur that gets somewhat sullied by imperial and orientalist overtones. Post-independence, the first round of national memorials dedicated to Gandhi and Nehru were self-effacing works—unimaginatively modernist or restorations of older buildings. The second round, with a more blatant political agenda like the Valluvar Kottam monument in Chennai or the pastiche BJP convention centre in Lucknow, are just plain ugly. The Lady with the Armani handbag clearly has an aesthetic vision in quite a different league to what has been seen in modern India. What then accounts for the one-sided vituperative that has been flung at Mayawati?

On a plaque in Persepolis, there is a quote from Ayatollah Khomeini: “I salute the talent of the ancient Iranians who created such beauty but condemn the cruelty of their kings who drove their people into creating this.” But Behenji is not quite a slave-driving Darius. She has won legal battles that allow her to use the state exchequer into the creation of Mayanagari and its sister sites across UP. At an estimated expense of Rs 3,000 crore, a criminal waste of resources one could say, but then, how different from the Keynesian nregs which is appositely accused of “digging trenches and filling them up”. Certainly not very different from the baroque and purposeless Bada Imambara here in Lucknow itself. Nawab Asaf-ud-Daulah, in response to the 1784 drought, paid people money to build it by day and then break it by night!

It is the motive of self-aggrandisement that lends the whole venture a sordid air. Sans that, Mayanagari and its allied sites would have changed Lucknow’s landscape for the better and Behenji could have safely written herself into a pantheon containing Ashoka, Shah Jahan and Lord Curzon. But the pantheon she’d rather be part of is narrow. She’s immortalised, in stone and metal, along with herself, Ambedkar, Phule, Birsa Munda, Narayana Guru, Kanshi Ram and Shahu Maharaj. Associating oneself with a group of safely dead, carefully reconstructed historical figures is one of the oldest tricks in the book of gaining political legitimacy. Arrogating a bit of the divine to oneself by paying obeisance to a reconstructed divinity is almost as well-known. But the scale of construction in Mayanagari is far greater than what is required to merely build political legitimacy. Mayawati must know this, and the setback in the recent LS elections must have further driven home the message. Yet, she goes on constructing at a frenzied pace, almost knowing that she may have just three more years to complete her dream project. There is more than mere extravagance or vanity or politics at play here.

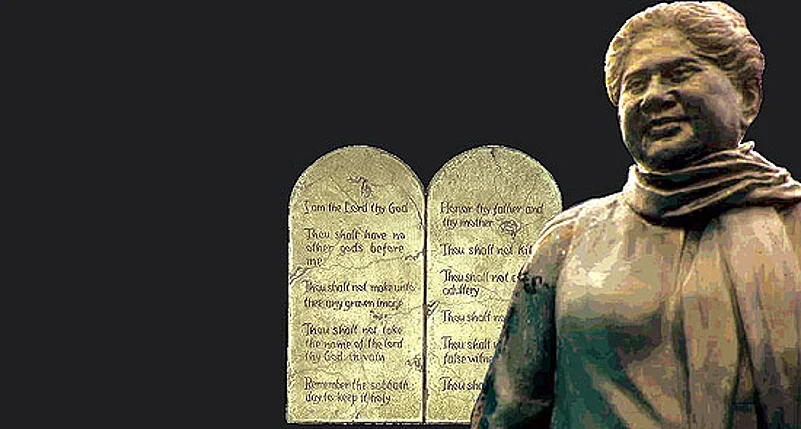

It’s an unfair caricature to say Mayawati is merely building statues of herself all over UP. In fact, she is building massive public spaces (something Indian cities are desperately in need of) in which there are statues of leaders who have worked for the Dalit cause. Is Mayawati merely a cynical, vain politician or does she see herself as a Moses leading her people to the Promised Land? And once in the Promised Land, don’t people need their myths, their prophets and their greatness cast in stone? For a Hindu can go to Taxila at the Khyber’s mouth and say “We did this”, or an NRI can wax eloquently about the Taj but what does a Dalit, now come of political age, have to establish the greatness of his identity? In a single sweep, Mayawati hopes to transform Dalit identity from that of an oppressed people to one of a great people capable of building grand monuments, for what else makes in history a great people?

Mayawati knows that if Mayanagari survives in stone and in the Dalit psyche, so will she. In the long run, thanks to their grandeur, they would have become an integral part of Lucknow’s landscape—bringing them down will be seen as ‘barbarous’. Behenji also knows that in the short run a demolition will be politically explosive. Canny politicians will know how important it is to let sleeping monuments lie.

(IIM-A alumnus Sitapati is marketing manager at a leading MNC)