Psychologically, the biggest change in Indian society in the last two decades has been the augmentation of hope and the stirring of its cousin, ambition. “Hope”, as the Mahabharata says, “is the sheet anchor of every man,” a truth that applies not only to individuals but also to communities and nations. Since hope is pre-eminently the province of youth, a part of the increase in hopefulness has to do with the country’s youthful population. This psychological ‘demographic dividend’ may be even more important than the economic one. The depressive ambiance that strikes an Indian visitor to many European countries, in spite of their vastly superior living standards, is not unrelated to their aging populations. Yet it is undeniable that liberalisation and the creation of economic opportunities have also played a role in enhancing hope.

Consider this man from a village in Rajasthan who is living in a Delhi slum. He works a back-breaking 14 hours a day on a construction site, lives with six other members of his family in a single-room tenement and eats, if at all, stale food in a chipped enamel plate. Yet he rejects the idea of life being better in his village with surprised astonishment. The city, with its possibilities, for example, schooling for his children, has provided him with a sliver of hope. The cynic might see his aspirations for a better life as completely unrealistic. But what keeps this man and so many millions of others cheerful and expectant even under the most adverse economic, social and political circumstances is precisely this hope, which is a sense of possession of the future, however distant that future may be.

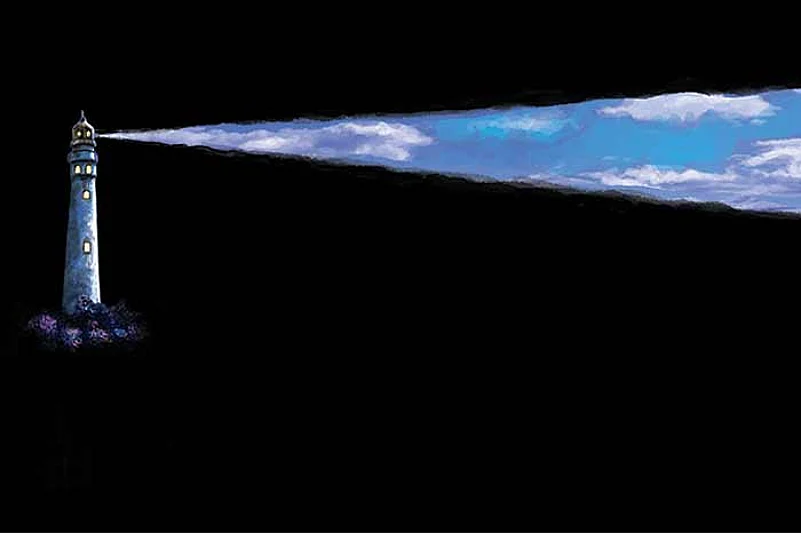

Change, though, is generally two-faced; the glass half-full has, as its corollary, the glass half-empty. Thus there is also a ghost of depression sitting at the banquet table laid out for the eagerly awaited dishes of 10 per cent economic growth, global power status and others yet to appear on the menu. The ghost represents the feelings of loss and helplessness of a large number of people who, as a consequence of liberalisation, are confronted with simultaneous loss of social status and identity as particular kinds of workers, as were the farmers at Nandigram. The ghost incorporates the feelings of humiliation of many whose cultural values and attitudes have been declared as outmoded by the winners of the liberalising project. To the losers, the ghost is the spectre of a future which is not only opaque but a threat to any sense of purpose. As the Mahabharata goes on to say about hope, “When hope is destroyed, great grief follows, which is almost equal to death itself.”

For those who are experiencing change less as a balmy breeze and more as a storm obliterating the familiar landmarks of their identities, the future is dark while the past appears brighter. Religious fundamentalism that harkens back to an ancient past and ideological primitivism from a more recent past are two sides of the same coin, both offering a diagnosis and cure for the suffering. It does not matter that the diagnosis is false; what is important is that it offers a sliver of hope for emerging from the feeling of being a helpless victim of superior forces over which one has no control. The consequence is an increase in membership of religious fundamentalist and ideologically fanatic groups that support a crumbling self the same way a scaffolding can support a crumbling building. The difference between the two is that the fundamentalist gaze is primarily turned inward as it bemoans loss, while the fanatic gaze is turned outwards as it screams oppression.

Another driving force behind changes taking place in many areas of social life is the middle-class Indian woman. The woman’s role as the prime mover of social change was made possible by two developments—one, an accelerated revision of the traditional view on the education of a daughter which encouraged higher education for girls and thus made their participation in work life possible, and; two, the growing financial needs of families, partly due to their higher consumption aspirations which welcomed the woman’s contribution to the family income, even when her work went beyond such traditional occupations as that of a teacher or nurse.

One consequence of these developments has been the woman’s higher self-esteem and potential for self-assertion which, in turn, have led her to demand greater emotional and sexual fulfilment in marriage than was the case with women of an earlier era. In other words, women today feel more entitled and are more vocal in their demand for a universal promise of marriage: intimacy, a couple’s mutual enhancement of experience beyond procreative obligations and social duties, a state of being that integrates tenderness and eroticism, human depth and common values. Today, slowly but surely, the middle-class woman is pushing the Indian family towards a greater acknowledgment, grudging or otherwise, of the importance (if not yet the primacy) of the marital bond, and a far greater recognition of the couple in the affairs of the larger family.

And the negative consequences? As middle-class disenchantment with other institutions of our society becomes rampant, the strains placed on the couple as a space that fulfils the quest for authentic experience may prove too much for this still-fragile institution. Whereas the movement towards the couple may indeed be desirable, a necessary corrective to the excessive ‘family-ism’ as I would call the traditional ideology governing intimate relationships, we need to be on our guard that this movement does not cross over into an extreme that is defined by a complete disregard of other family ties.

Similarly, a greater openness to the manifestations of sexuality—in life as also in cinema, art and literature—is indeed a welcome antidote to the moralistic repressions of an earlier era. Yet we also need to be aware that the search for the erotic does not lie in aping western sexual mores where eroticism is fast disappearing under the flood of pornographic smut and the babble of scientific sexology.

The coming to fore of the couple is also weakening the traditional ideology of fatherhood with its decided notions of things that men do in household and childcare, and others that they don’t. Playing with or taking care of their infant and small sons is not what fathers did, their major role lying in the disciplining of the child. Today, fathers are more actively involved in bringing up their infant and small children. They have begun to provide early emotional access to the son, not only attenuating the overheated quality of the mother-son bond, but laying the foundations for a less hierarchical and closer father-son relationship. The early experience of fathers who are no longer distant and forbidding figures, who are available to both sons and daughters, often as playmates, cannot but help in moulding modern Indian notions of what should be the desirable distance in power, prestige and status between people occupying different positions in organisations in a more egalitarian direction.

The half-empty glass? The mounting expectations of youth for more egalitarian relationships has the potential for increasing conflict between generations. We must remember that although a modicum of such conflict is desirable for renewing a society’s institutions, we also need to ensure that it only stretches the generational bonds and does not snap them altogether. On the whole, psychological changes during the decades of liberalisation are undermining the obsolete and ossified elements of traditional Indian identity. I hope that the excesses of these changes will be tempered with time and that Indian identity will evolve in such a way that both its historical continuity and its integration with a changing environment, now global, are maintained. Hope is not only a possession of the young.

The author is a psychoanalyst and writer.