This story is based on true events. So there I am, shuffling in a cushioned chair before the mahagony desk of a film corporate baron. Award trophies crowd the shelves. Salt-and-pepper-haired, just like myself, the baron’s powder-blue shirt is buttoned-up over fashionable stressed jeans. “Will you have chai or coffee?” he asks. Cut to the instant machine-brewed mug of cappuccino, which throws up steam on yet another afternoon in Cinema Paradiso.

The new game in town—or negotiations, if you prefer the word—is to pitch.

Go armed with the concept, the story idea and, more importantly, the intended star cast. Maybe the corporate will smile, flashing his pearlies; maybe he won’t.

I’m carrying a detailed script of Rutba, a sequel to Zubeidaa (2001), which I had written for Shyam Benegal. The decision-making corporate is mildly interested. “Who will be the actors?” he quizzes me, brows knitted. “As you know, everything depends on that.” I tell him I have to get around that chore, once there is a nod from him or, frankly, the next company in the daisy chain.

“Look,” he enlightens me with his under-the-Bodhi-tree-like wisdom. “If you can get any of the three top Khans, you’re on at this very minute. If you can organise Ranbir Kapoor, Varun Dhawan or Ranveer Singh, fantastic, we’re ready to invest Rs 25 crore-plus. If you’re thinking Manoj Bajpai, Irrfan Khan or Nawazuddin Siddiqui, you’ll have to bring it under Rs 10 crore…if they’re on, best to do it in seven or eight. Get it?”

“I do. But the script’s woman-centric. I need three strong female artistes, not males.”

To that the response is, “Tough, tough. I know some women empowerment films have clicked. Content is king and all that. These are exceptions, not the rule. Buddy, can’t you change the gender of your characters? Just a suggestion.”

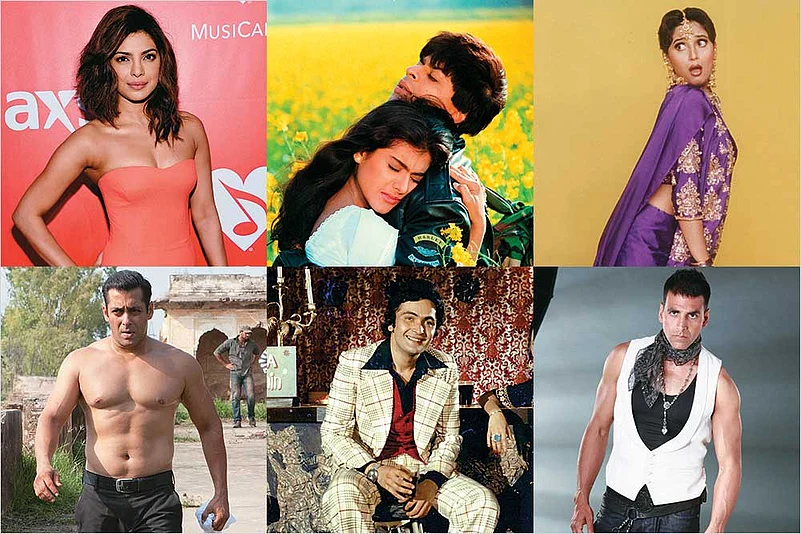

(clockwise from top left) Priyanka Chopra, SRK and Kajol, Madhuri, Akshay Kumar, Rishi Kapoor, Salman Khan

Hell, gender always turns out to be a deal-breaker. I have wasted his and my time. Before the coffee can cool, I have left the glass-panelled building.

Over two decades now, corporate film companies have sought to rewrite the rules of Bollywood cinema, acknowledged as the key and the most far-reaching segment of India’s film production. Alongside the yearly harvest of films from Mumbai and the prolific output from other states, India’s entertainment industry has preserved its status as the largest of its kind in the world. Come recession or calamities, movie entertainment is where the big bucks are.

In principle, corporates are more transparent in their business dealings than the traditional dream merchants. These congolmerates, some backed by foreign investors and others by local business tycoons, seek to facilitate streamlined, cost-effective productions.

This template may be an ideal one on paper. In execution, however, it hasn’t exactly been a dreamwalk. More than half-a-dozen film corporates have packed up. As for the survivors, they are being cautious to the point of being timid and unilateral—attributes not exactly conducive to creative film-making.

Way more than their predecessors—the traditional film-makers who once worked out of the Naaz office at Lamington Road—the corporates are averse to risk-taking. Inadvertently perhaps, they have exacerbated the oft-rued star system by attracting stars to their fold, offering them incredibly inflated salaries and even a hefty share in box-office profits. Not suprisingly, Shahrukh Khan, Salman Khan, Aamir Khan, Akshay Kumar and Ajay Devgn, among others, have established their own home film production banners. Hrithik Roshan acts, regularly, for his father Rakesh Roshan’s film banner. Of the leading ladies, Priyanka Chopra, juggling between international and domestic projects, has initiated a film production company in partnership with her mother.

No female star, at this juncture, is billed as the numero UNO draw like Hema Malini, Sridevi and Madhuri Dixit were in their prime. Sure Deepika Padukone and Priyanka command enormous fees, the generation after them being led by the flavour of the season, Alia Bhatt. Admittedly, Alia has adroitly balanced her career in larger-than-life mainstream cinema with films (Udta Punjab and Highway, for instance) that stray off the cliched track.

Meanwhile, the once-fertile independent cinema is today reduced to a trickle.

The parallel or New Wave Cinema of the late 1960s and ’70s is inconceivable today. The central government, regardless of who runs it, is no longer committed to allowing a thousand flowers bloom. Like it or not, the National Film Development Corporation, which funded progressive and experimental cinema—a substantial lot of them directed by Film and Television Institute of India graduates—has been reduced largely to a marketing organisation. The official bodies, be it the Children’s Film Society of India or the Films Division, are in a state of coma.

I’m not indulging in reductive generalisations or whining over sour grapes. That Bollywood film production has become monopolistic is a fact. The stars, directors and producers who slam out high-profit hits, at jaguar speed, form the elite club, especially since the multiplex boom across the nation. The Rs 100-crore-plus earners comprise the power list. Piquantly, the opening weekend collections can make or break fortunes.

Consequently, every film has to reserve a cushy part of the budget for the pre-release publicity hoopla. This feat is achieved through social media sites, a flurry of promotional trailers, paid-for spreads in the entertainment supplements of newspapers and press conferences in multiple cities at home and abroad. If this military-like operation eats into the budget, which could have been expended on a film’s quality, so be it. No buzz, no house-full show.

Neither is film viewing an affordable and impulsive means of entertainment.

A tub of popcorn at the multiplex can be more expensive than the cost of a ticket, which has never been as pricey as it is today. Single-screen auditoria cater essentially to seekers of rough-and-tumble entertainment.

Most of Mumbai’s single screens, for instance, show re-runs of Mithun Chakraborty and Govinda action flicks, besides Bhojpuri films. Meanwhile, the glossies make a killing at the multiplexes; online bookings witness a spurt for the Khans and, of late, for Akshay Kumar and Varun Dhawan movies.

Now that’s in the fitness of the movie-going habit. Since time incalculable, before venturing out to a matinee, there’s that chestnut of a question, “But who’s starring in it?” If a song or two of a film has caught on, that’s a bonus.

Eye-dazzling special effects, comparable to those of international cinema, can be a powerful draw on occasion. Prominent example: the two Bahubaali extravaganzas, dubbed from their original Tamil and Telugu versions into Hindi, have registered all-time record-breaking collections. And yet they needed the backing of Karan Johar’s Dharma Productions banner, to make a whopper impact in the all-India market.

The trend, as it happens, is that there’s no trend. No one genre is the audience’s preferred option. Any genre can click, be it action, romance, a sexist comedy or a biopic. This engenders a variety of movie fare, but chances of commercial success are dicey.

To play safe, in the current scenario, franchises of films have connected with the mass audience. Take Golmaal Again, featuring Ajay Devgn and Parineeti Chopra. The fourth edition of Rohit Shetty’s low-brow laugh-raiser has emerged as Bollywood’s topmost ticket-seller of the year. The collections are said to be over Rs 200 crore and still counting.

Two of the year’s biggest disappointments, which underwhelmed the masses as well as the mandarins, were Salman’s misadventure Tubelight and Imtiaz Ali’s Jab Harry Met Sejal, showing the 52-year-old Shahrukh cavorting across Europe with the 29-year-old Anushka Sharma.

Does advancing age diminish the allure of superstars? Should the Khans (all aged 52, coincidentally) be waking up and smelling the latte? From what can be guesstimated, they already have. Salman, after the cry-baby act of Tubelight, isn’t likely to futz around with his patented macho, invincible image again. Shahrukh’s next project, still untitled, casts him in the role of a dwarf. Yesterday’s marshmallow-soft lover boy, the Raj Malhotra of Dilwale Dulhaniya le Jayenge, surely needs to involve himself in films that allow him to display his unquestionable acting chops.

Fortuitously, Aamir is the most foresighted one of the trio, segueing into elderly father roles (Dangal) and isn’t hesitant to make a guest appearance, as a flamboyant music composer in his home production, Secret Superstar. For Yash Raj Production’s high-budget Thugs of Hindostan, a scruffy make-over doesn’t faze him. Obviously, exuding good looks, once mandatory for heroes, isn’t a calling card any longer.

Akshay is into reinventing his Khiladi swag, with life-like avatars initiated with quasi-biopics Airlift, Rustom and the upcoming Padman. His strategy is to present himself as a devout nationalist. So far, that has worked in his favour, particularly with Toilet: Ek Prem Katha, which was aligned with PM Narendra Modi’s Swachh Bharat campaign.

(clockwise from top left) Ranveer Singh, Alia Bhatt, Parineeti Chopra, Ranbir Kapoor, Deepika Padukone, Aamir Khan, Anushka Sharma, Ajay Devgn

Business-savvy, in the way Jeetendra was once, Akshay’s priority is to preserve his professional longevity. Naturally, he will persist with the no-brainer movies, too, going by his reported assent to the fourth edition of the knockabout comedy franchise Housefull. Once considered a non-actor, the 49-year-old was even judged the Best Actor at the National Awards for portraying the real-life Nanavati in Rustom.

For better or worse, the face of the Bollywood hero, has altered dramatically. To ascribe the lasting reverence for the actors of the 1950s—the Golden Age of Hindustani language cinema—to sheer nostalgia, would not only be patently wrong, but also unfair. The millennials may not be familiar with the versatile range of Dilip Kumar, the thespian of all thespians. When I asked a batch of college students about him, they asked, “Who’s he?” Only one said uncertainly, “Wasn’t he in Mughal-e-Azam?”

I didn’t subject myself to more disbelief by asking if they were familiar with Raj Kapoor and Dev Anand. How could they be? At most, the generation born after the 1980s, do express a regard for Amitabh Bachchan. But the most charismatic tridev of actors of all-time—Dilip Kumar, Raj Kapoor and Dev Anand—merely point towards re-runs of the classics on television. Sad to say, black-and-white are off-putting for the now generation.

Apart from a discriminating minority of millennials, there’s little curiosity about the actors who set the standards of consummate acting. Balraj Sahni, Motilal and the aforecited trio are still on the memory files of filmgoers, but mostly among the age-group of 40-plus.

Similarly, the lasting fascination for Madhubala, Meena Kumari, Nutan, Geeta Bali, Sadhana and Waheeda Rehman can be sourced essentially among those who have cared to look back or treasure the past with affection. A sizeable section of the present-day teenage viewers are clueless about them.

In fact, the post-Independence decade of the 1950s had yielded a treasure-house of films remarkable for their rooted-to-the-soil stories, chaste dialogue, unerasable music scores, besides actors for whom quality superseded quantity. Dilip Kumar, the highest-paid actor of that decade at the then princely sum of Rs 1 lakh, cherry-picked his assignments and directors. To a degree, Aamir has followed his example and is respected for being selective.

The 1960s witnessed a boom of breezy entertainers often located in hilltowns and in Kashmir. Shammi Kapoor’s ‘yahoo’ call became anthemic; Dharmendra rocked as the iron-fisted man with a heart of gold; Manoj Kumar aka Mr Bharat became the advocate of patriotic fervour.

Towards the end of that decade, the vulnerable romantic Rajesh Khanna arrived to entice the nation into a frenzy. The first superstar in Bollywood, the hysteria was sky-high, since he gallantly assured life was a bed of roses for the heroines paired with him frequently, notably Sharmila Tagore, Mumtaz and Asha Parekh.

Concurrently, Jeetendra earned the epithet of Jumping Jackflash with his free-form dancing. Rishi Kapoor became the poster-boy of bubbly romances, while Vinod Khanna and Shatrughan Sinha double-tasked, in an unusual development, both as fearsome baddies and do-gooders.

With the declaration of the Emergency (1975-’77), the audience craved a new kind of hero: someone who could take on the Establishment by venting his bottled-up rage. Ironically, Amitabh, who was close to then Congress PM Indira Gandhi’s family, became the emblem of angst (facilely described as ‘the angry young man’).

Rajesh Khanna was left out in the cold. Amitabh was crowned the next superstar, an exalted status he occupies even today at 75, thanks to his indefatigable pursuit of film roles commensurate with his age, enhanced by the ongoing success as the congenial host of TV series Kaun Banega Crorepati.

The word ‘superstar’ has been quite randomly applied of late. Amitabh is still described as one, never mind that he was left looking askance when the three Khans became the most-wanted heroes, circa the 1990s. When Amitabh’s heroines changed from Hema Malini and Rekha to leading ladies half his age (Meenakshi Seshadri, Manisha Koirala and Shilpa Shetty), there was a distinct discomfort among the audience. The Khans, all compactly framed and boyish, were ready to take over from the looming, six-foot-plus Amitabh. And that happened in a flash.

As we move towards 2018, the Khans carry on. Alternatives to the movies—television soaps, web series and the array offered by the streaming channels Netflix and Amazon—are attracting more eyeballs in the metropolitan cities.

However, old habits aren’t exactly dispensable. Bollywood cinema is still the main course of the entertainment diet. Or else why would thousands of film-makers, wannabe or established, continue to pitch movie projects to corporate honchos?

The only paradox I notice is that the corporate bosses have begun to suggest sagely, “Okay, if not a feature film, can your script be stretched into a web series? That’ll be practical, and I may add, earn us…and you more money.”

In the event, the coffee steams on, and how you long for the golden 1960s, when cinema was king.

(The writer is a veteran movie journalist, scriptwriter and film-maker.)