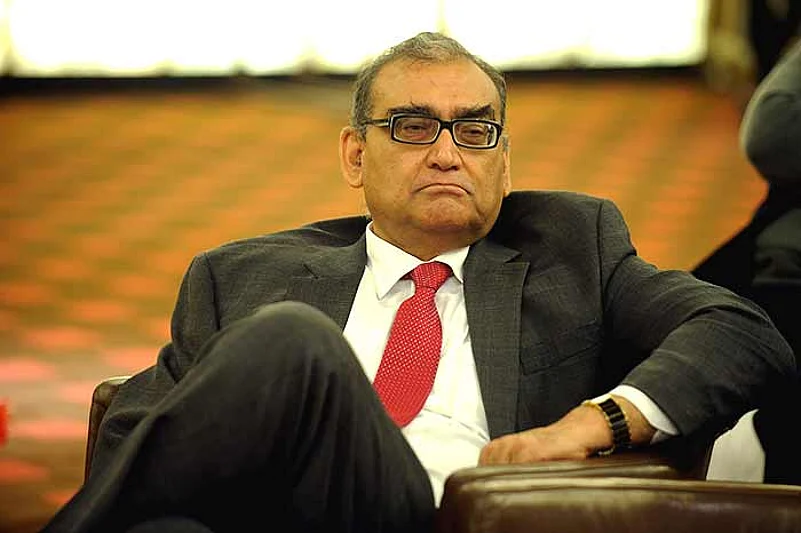

A simple question is bugging the Indian media today. Are the almost daily commentaries on the sins of the media by the rather recent chairman of the Press Council of India, retired justice Markandeya Katju, the natural outcome of an irresistible urge to use his office as a unique national pulpit? Or does it signify more, maybe even in terms of government intentions? The Press Council, fashioned after its UK counterpart, was formed on the understanding that an expert organisation leavened with public representatives should have the ability to shame publications/journalists for wrongdoing. Justice Katju now wants punitive powers (“more teeth”) to change the character of the body, and he wants electronic media and the internet brought within its purview.

More often than not, he is on a media-bashing blitz, majestically declaring at one moment that 90 per cent of our media, especially electronic, panders to reader/viewer tastes because “90 per cent Indians are very backward, of poor intellectual level, full of casteism, communalism and superstition”. Reflecting his own reading preferences, his ideal for the Indian media is the British phase of the 17th-19th centuries when men like Bagehot inspired the people. We have learnt by now that Katju has an opinion on everything. Salman Rushdie is a poor writer. Awarding the Bharat Ratna to cricketers like Sachin Tendulkar would be a travesty. Cricket is the media-fuelled opium of the Indian masses. The media lack a sense of proportion. His erudition, incidentally, encompasses Ghalib and Tulsidas and, of course, Voltaire.

Sometimes, Katju springs to the defence of journalists and peremptorily asks the Maharashtra government to protect them or berates Bihar for denying press freedom before investigating the complaint. Questioned whether all journalists are bad, he concedes in an undertone that there are some good ones. But his poor opinion of Indian publications and TV channels is broadcast more often, and widely. Self-regulation, he asserts, is no regulation.

It is hardly a wonder then that the first meeting of the newly-constituted Press Council led to a walkout by some media representatives after Katju refused to withdraw his censorious remarks. There is no getting away from the bugging question: is there a method in all this? Apart from indulging in his own propensity to dispense wisdom on human civilisation, is he performing the government’s task of softening up public opinion to clip the media’s wings? After all, if print and electronic media are so pathetic, is there much point in giving them freedom of expression? In information minister Ambika Soni’s view, he is initiating a debate.

Let’s then change the Press Council’s character by giving it “more teeth”, and as Katju’s definition expands, “in extreme situations” impose fines, deny government advertising (shades of the Emergency?) and even withdraw the printing or electronic licence. A universal principle of a free media in a democracy is that it cannot be judged by a government-formed body, that policing can only be conducted by peers, albeit within the confines of legitimate laws.

It is no one’s contention that the Indian media is flawless or as good as it can and should be. There is some bad, if not motivated, reporting. The evils of “paid news”, purchased material passed off as professional reporting, are obvious. Television news often tends to run away with one story, to the exclusion of the rest of the news in the country and the world. Spoken English by anchors should, but often do not, pronounce words correctly and accent the wrong syllable. There is a lack of consistency in standards of excellence in even well-regarded broadsheets and there is a wide gap between how English is written in the editorial and opinion pages and in news stories. The bane of “breaking news” for the most trifling of events often overwhelms 24/7 news channels.

Still, even with these deficiencies, there are some excellent investigative stories in print and electronic media. Some TV channels do an impressive job in putting together the main newscasts and incisive interviews. And computer software does wonders in making news pages attractive, but for the excessive, and unjustified, liberties taken by the ad departments. But Indian media as a whole is a vigorous, sometimes rumbustious, phenomenon the country can be proud of.

Let us not take the aberrations to be the norm. Free media will necessarily have an adversarial relationship with authority; the honorific of the Fourth Estate speaks for itself. But there is mutual recognition on the limit of each side’s powers. Justice Katju should stop treating the media like spoiled children or undertake ego trips to further his own, or the government’s, objectives. The price of democracy is dissent and honest dissent within the bounds of public decency and lawful rules is greatly to be encouraged for the well-being of the people and the good of the nation.

(The author is ex-editor of The Statesman and Indian Express)