Rahul Dravid is gone, V.V.S. Laxman too, and now Ricky Ponting has joined them in the arena outside the stadium called ‘real life’. Mahela Jayawardene speaks of making way for a youngster, and he is only 35. Send not to know for whom the bell tolls, it tolls for us. Retirements are reminders of our own mortality.

A sporting career does not exist in a vaccum. It needs fans to complete it—the yin to the onfield yang. Fans who measure their lives in goals scored and runs made by the great players have to readjust their sights when these names leave the scene. More, they are made acutely conscious of a significant portion of their own lifetime being enshrined as history. The cliche ‘end of an era’ applies not just to the impact of the recently retired; it speaks for the millions who will never see a favourite in action again.

This is a painful period for fans of the modern greats. Jacques Kallis, 37, must be having private chats with himself. And what of Sachin Tendulkar, set to turn 40 in four months, by which time he will have been playing for 24 years?

My son was a year old when Sachin made his international debut. Sachin has been as much a part of his growing years as falling off bicycles, homework in school, maidan fantasies, rock concerts and quantum theory. A whole generation, born when the Berlin Wall was standing and the Soviet Union was a superpower, when Nelson Mandela was still in prison and Mike Tyson was deemed unbeatable, might barely remember how things changed. But Sachin was at the crease, and all was right with the world.

It is not unusual for sports fans to bookmark their lives with the performances of their heroes—wedding anniversaries as adjuncts to a national win or a great individual performance. Tendulkar might have played international cricket for over two thousand days—at least some of those are bound to have coincided with significant dates in the lives of millions. Where were you when V.V.S. Laxman made his 281 in Calcutta? Or when Rahul Dravid made 148 both in Johannesburg and then in Leeds? These two, firm friends, quit within days of each other, announcing their decisions at press conferences. Not everybody is so lucky.

Nor does everybody finish with a century like Greg Chappell did, or even a double century like the West Indies star Seymour Nurse. Players from the subcontinent have usually had to be pushed out. The great Kapil Dev had become a pale shadow in his final Tests. He was carried around so he could overtake Richard Hadlee’s record for most wickets. Gundappa Vishwanath played on after a traumatic tour of Pakistan, hopeful of a recall. Pakistan’s stars retired and unretired with comic frequency.

Sunil Gavaskar went with dignity after a fabulous innings of 96 on a rank turner (a phrase reintroduced into common currency by Mahendra Singh Dhoni) in Bangalore. He invited a few reporters to his room, thanked them for their support, and then said that the Lord’s bicentenary match in England would be his final one. He made 180-plus for the World XI—at a venue where he famously did not have a Test century.

The longer you play, the more difficult it is to leave. And the more difficult it is to read the tea leaves with any clarity. You think that the game-changing innings is just around the corner. Surely Ponting believed that if he grit his teeth and hung on against South Africa, he might make runs and redeem himself in the Sri Lanka series to follow?

Men who play for long—17 years in Ponting’s case—do so because of a combination of passion and pride. No one likes their world to end with a whimper. But when a bang does occur, the temptation is to believe that the worst has been overcome and the salad days are back. To make a century (or 96) and quit because you feel in your heart that you didn’t move well enough or let mediocre bowlers dictate matters to you for long spells—that requires a high degree of self-awareness. Sometimes the knowledge comes in a flash. In the case of Adam Gilchrist, it came when he dropped a relatively straightforward catch from Laxman. Suddenly, he knew it was over.

The reverse is possible too. The certainty that it isn’t over yet. A couple of years ago, Dravid was going through such a terrible patch that the ‘R’ word was being bandied about freely. His best innings ended under 20; his worst went on for long and put on display all the weaknesses, natural and acquired. Yet, clearly, as subsequent events showed, the time hadn’t come. If Dravid had quit then, he—and we—would have been deprived of those centuries in England, where he became only the second batsman after Don Bradman to make three in a single series.

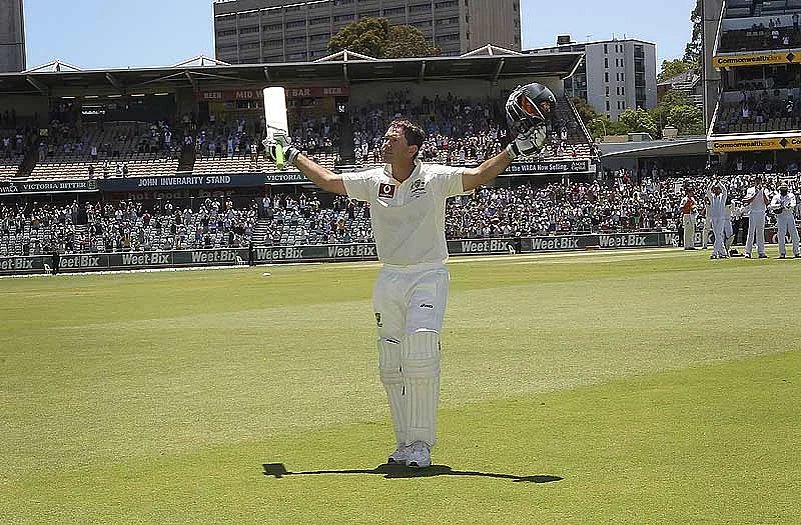

When Ponting called it a day, he made one thing clear: “This is not a decision that’s been made by the selectors, this a decision that’s been made by me. There were probably moments when they thought long and hard about ending my career and I’m glad I’ve got the opportunity to finish this way and on my terms”.

This is going out in the manner of Sinatra’s song—My Way—and is the dream of every sportsman. The fantasy involves quitting at the top, winning the final match for your team, and moving aside without any regrets. It is tough, as Tendulkar is discovering now. When you know nothing except the game and then that is taken away from you, nothing remains but a dark abyss. No country has a system that helps players psychologically at the end of their careers. To tell them that the end of a career in sport is not the end of the world.

Dravid made the point that players used to the adulation and respect of being at the top of one profession find it difficult to adjust to being second best in any other. Hence the temptation to postpone the inevitable.

I have a friend on a wheelchair who loves to drive. One holiday we drove for miles. He told me the destination was incidental, the drive itself was fulfilment: “It is when I am in control.” The cricket field is where Tendulkar is in control, and it is understandable if he doesn’t want to let go.

Sport can be cruel. Before you properly mourn the passing of one champion, another is ready to take his place. When Gavaskar quit, there was much breast-beating. End of an era. Two years later, Tendulkar appeared. Similarly with Viv Richards and Brian Lara, Allan Border and Ricky Ponting.

The Dravids and Laxmans and Pontings and Kallises and Tendulkars are our heroes—they will not necessarily be the heroes of our children and grandchildren. Vinoo Mankad, whom Virender Sehwag hadn’t heard of, was my father’s hero; Virat Kohli is my son’s. The first Test match I reported on outside India was the one in which Tendulkar made his debut. In cricket, we are joined at the hip.

Fans have their Tendulkar moments, their Ponting moments. In the end, the records don’t matter. What matters is the shared consciousness. They came, we saw, and we concurred. Their talent enabled us to conquer everydayness. Our expectations goaded them further. It was symbiotic. We mourn because each time a sportsman retires, he peels away another layer of what makes us who we are.

(Suresh Menon is Editor, Wisden India Almanack, and author, most recently, of Bishan: Portrait of a Cricketer)