The 2002 elections for the 117-member Punjab Legislative Assembly were held on January 30. In the poll results, the Congress – Communist Party of India (CPI) combine defeated the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) - Bharatiya Janata party (BJP) coalition. Elections were held for 116 of the 117 seats because a candidate died while the polling process was on.

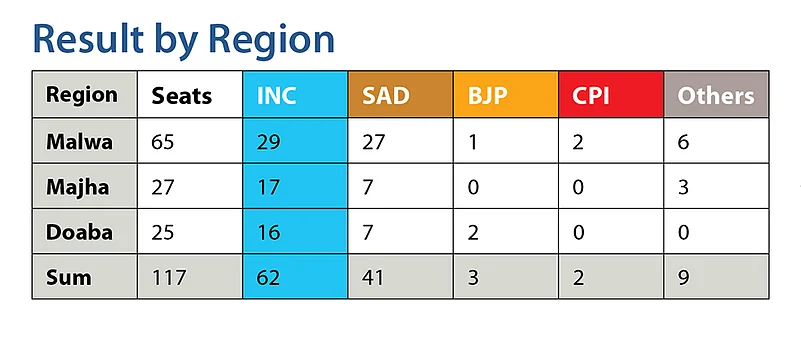

The poll witnessed a stiff, two-cornered contest between the Congress-CPI and the SAD-BJP combines. Congress–CPI won 64 seats of which the CPI won two, SAD-BJP combine won 44 seats (SAD-41 and BJP-3), and independent candidates got an unprecedented victory on nine seats. A total of 62.14 per cent votes were polled. The poll verdict was contrary to the results of the poll predictions and the exit polls outcome.

A total of 1.02 crore votes were polled in the state elections, out of which the winning Congress party got 36.82 lakh votes constituting 35.81 per cent of the votes electorate, SAD (31.96 lakh votes) with 31.08 per cent, BJP (5.83 lakh votes) 5.67 per cent, CPI (2.2 lakh votes) 2.15 per cent and independents (11.59 lakh votes) a considerable vote share of 11.27 per cent.

Ahead of the polls, the Congress ran a high-decibel poll campaign against the SAD-BJP combine. The Congress, during the canvassing and even months before that, focused on levelling allegations of corruption by the incumbent SAD-BJP coalition government. It accused the government of irregularities in recruitment in different government departments and in the Punjab Civil Services and judicial services. The Congress directly blamed Punjab Public Service Commission chairman for openly receiving kickbacks for selecting candidates. The SAD-BJP was on the defensive. Capt. Amarinder Singh led the Congress to victory.

Dissecting region-wise victory of seats in Malwa, the Congress and the SAD were neck and neck wining 29 and 27 seats respectively. In Majha, the Congress took a considerable lead, winning 17 seats, while the SAD could win only seven out of the total 65 seats. In Doaba also the SAD received a drubbing as it could win only seven seats and teh Congress won 16 out of total 25 seats. The CPI won two seats in Malwa, its area of foothold, independents won six in Malwa and three in Majha and the BJP was victorious on one seat in Malwa and on two in Doaba.

The CPI could not win any seat in Majha, considered an Akali stronghold. The Congress managed to sway the voters in Majha by highlighting Capt. Amrinder Singh’s panthic credentials. During the campaign, Capt. Amarinder Singh, who became chief minister after the poll results, played up his panthic credentials underscoring that he resigned from the Lok Sabha and the Congress after Operation Blue Star, the army action on Golden Temple to flush out extremists.

Once the de facto ruler of upper parts of the Malwa belt in Punjab, former Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) president Gurcharan Singh Tohra, known as the leadrer of the panth (the Sikhs), was wiped out in his bastion in the assembly elections of 2002. (SGPC was formed with an Act of Parliament and manages historic gurdwaras.) Tohra was then opposed to Badal-led SAD.

The veteran leader remained most effective in his home constituency of Amloh in which Tohra village falls, managing to get 13,309 votes for Harnek Singh Deewana, the Panthic Morcha candidate.

However, even in this constituency, Deewana was much behind the SAD candidate and a former Tohra loyalist Gurdev Singh Sidhu who secured 26,633 votes. The winner, Sadhu Singh of the Congress, was much ahead with 45,383 votes and could not have been defeated even if the votes of the SAD and the Panthic Morcha candidate had been combined.

In Sirhind in Fatehgarh Sahib district, the Panthic Morcha candidate, Iman Singh Mann, son of veteran Akali leader Simranjit Singh Mann, securing only 19,235 votes, trailed far behind the SAD candidate. The SAD candidate Didar Singh Bhatti, a political novice who only had the advantage of the SAD ticket, was able to secure 32,528 votes and lost to Congress candidate Harbans Lal by a margin of little over 3,000 votes.

In Patiala district, Tohra could do little to make any of his candidates finish second or even be in a position to spoil the chances of the SAD candidates. In Patiala town, the Panthic Morcha candidate Jaswinder Paul Singh Chaddha was able to secure only 725 votes. Similarly, the Panthic Morcha candidate Dalip Singh Sooch polled only 2,412 votes compared to SAD candidate Ajaib Singh Mukhmailpur who secured 29,339 votes. Though the Panthic Morcha candidates fared better in other constituencies, they were outstripped by independents in a few of the constituencies of the district.

The people of Punjab have voted in favour of the two main political rivals for power, the Congress and the Akalis, and rejected other splinters groups, parties and organization.

The results showed that rural constituencies stood behind the Akali government, and the presence of the Panthic Morcha candidates and the fast-paced campaign by its leaders, including Gurcharan Singh Tohra, failed to make any dent in the vote bank of the ruling Akali Dal. Interestingly, if the BJP - which faced complete rout in the urban constituencies - managed to win just three seats, Garhshankar, Ferozepore and Hoshiarpur, it was mainly due to the large number of villages falling in the three constituencies. That, political observers said, was an indicator that the much hyped “anti-incumbency” factor did not affect the rural electors as much as it affected the urban voters, who were swayed by the reports of the electronic media and a section of the print media.

Even corruption, it seems, did not impact the polling much. The only factor that ultimately swung the poll pendulum in favour of the Congress was the refrain of change that people wanted and the impression created by the Congress’ shrill ad-campaign promising a “clean” administration.

Political Dynasties Of Punjab

The network of deras and politicians has resulted in the rule of a few families in Punjab politics for a long time. As per the estimates, the state has one of the highest proportions of MLAs with dynastic links. Six families — the Badals of Muktsar who generations ago migrated from Majha’s Moose village, the Patiala royal family currently led by its scion Capt. Amaridner Singh, the Majithias of Amritsar, the Kairons of Tarn Taran, the Brars of Sarai Naga, and the Manns of Sangrur — have dominated the State political landscape for more than three decades.

These families are linked to each other through marriage. Capt.Amarinder Singh and Simranjit Singh Mann are married to sisters Preneet Kaur and Geetinder Kaur, HS Brar with Pratap Singh Kairon’s niece, while Kairon’s grandson Adesh Pratap is married to Parkash Singh Badal’s daughter. Harsimrat Kaur, daughter of Satyajit Singh Majithia, who was the deputy Defence Minister during Jawaharlal Nehru’s regime, is married to Sukhbir Badal.

There are new political families rising on the political scene whose members have been elected from various parties. For example, the Ludhiana-based Bains brothers, who had aligned with the Aam Aadmi Party this time, won their respective seats second time in a row by a significant margin.

Party Dynamics And Axes In Punjab, 1967 To 2007

An analysis of seats won by the SAD in all elections between 1967 and 2007 shows that it had a clear edge in 22 seats and a majority of these were predominantly rural.

In the post-terrorism period, the urban Hindu traders, in response to the pre-election alliance of the BJP based on Hindu-Sikh amity have shown preference for the Akali Dal.

The Akali’s urban vote share in 2007 increased to 17 per cent from 16 per cent in 1997 assembly elections in pre-election alliance with the BJP. There have been qualitative shifts in the Akali support base. The first shift took place at the time of reorganisation of Punjab coupled with the Green Revolution. The rural Jat Sikhs constituted its main support base and its leadership also came from this section.

A comparative analysis of the vote share shows that the Akali Dal secured the maximum votes in rural constituencies: 43 per cent in 1997 assembly elections and around 17 per cent in urban constituencies in 2007 assembly in the pre-election coalition phase. The consequence is, it articulates the agrarian interests and appropriates Sikh religious symbols for blurring the emerging contradiction between the agrarian and other sectors of the economy.

The second shift took place in 1985, in the aftermath of Operation Blue Star and anti-Sikh riots. The Akali’s urban vote revolved around 5 per cent, but in 1985 it touched the 12 per cent mark with the active support of urban Khatri Sikhs. The third shift took place after the resurgence of democracy in 1997, when a substantial number of urban Hindus supported the Akali Dal.

Paradoxically, the Congress has to compete with a strong regional party, but within the boundaries defined by the national leadership. The only action which seems to have defied this has been the Punjab Agreement Repealing Act 2004 on Sutlej Yamuna Link canal (SYL) passed by the Punjab Assembly much to the annoyance of the national leadership of the Congress.

The Congress mainly focused on wooing the rural Jat peasantry. Traditionally, its core support base consists of a large majority of Hindu dalits with their ‘uncertain religious allegiance’, urban Hindu traders, Sikh Khatris and migrant landless labourers. A small faction of the rural Jat peasantry also supports the Congress because of village level factionalism, kinship ties etc. An analysis of party activists shows that 67 per cent are Hindus. They comprise businessmen (38 per cent), petty shopkeepers (32 per cent), farmers (16 per cent) and unskilled workers (6 per cent).

An analysis of the percentage of seats won from 1967 to 2007 shows that the Congress has a strong base in the urban constituencies and the dalit-dominated Doaba region of the state. Further, analysis of vote share between 1997 and 2007 shows that the Congress secured maximum of 46 per cent of the votes in 2002 elections in the urban constituencies and 39 per cent in the Scheduled Caste dominated Doaba in 2002 elections.

SAD rally Dera Baba Nanak (Photograph by Prabhjot Singh Gill)

However, after Operation Blue Star and the brutal riots against the Sikhs in 1984, the Congress was projected by rivals as being anti-Sikh. Its alliance with the CPI in 1990s was to overcome the accusation of being anti-Sikh and therefore, communal. The Congress support base has kept changing in response to political developments in the state. In the initial years, till the mid-1960s, the rich and middle peasantry supported the Congress which, under the leadership of Partap Singh Kairon, initiated reforms in the rural areas.

Between 1967 and 1980, the Congress support base shifted to urban Sikhs and Hindus, the Scheduled Castes, and a small section of the peasantry. In post-Operation Blue Star period, in 1985, a section of urban Sikhs shifted to the Akali Dal.

However, in the 1992 elections held in the background of pervasive terrorism, most of the elected MLAs were from rural background and were young. The change in leadership shaped the future politics and brought a qualitative shift in the agenda of the Congress.

The BJP has been traditionally seen as a party of urban Hindus. Around 95 per cent of its party activists were Hindus. They are involved in trade and business (50 per cent) followed by small business (32 per cent). An analysis of assembly election results between 1967 and 2007 shows that the BJP has its presence in urban and semi-urban constituencies.

Traditionally, the BJP has opposed the Akali demands of Punjabi Suba and a Sikh homeland. However, in the post-terrorism phase, the shift in the stance of the BJP from strong Centre to greater autonomy for the states and its opposition to Operation Blue Star and the November 1984 riots increased its acceptability among the rural Jat peasantry. It was mainly political considerations, rather than electoral arithmetic, which nurtured the pre-election alliance.

SAD president Prakash Singh Badal was of the view that the SAD’s alliance with the BJP was historical and political. It was not an opportunistic alliance. Another senior leader of the SAD who was opposed to the alliance considered it as an electoral burden and which was diluting the ideological base of the Akali Dal. A quick glance at the data show that the SAD has gained in pre-election coalition. However, the BJP has suffered major losses.

The BJP’s loss has been the gain of the Congress as both parties compete for the same support base. The regionalisation of the Congress has ensured its continuation as a major political party in the state. In other words, its continuation has been shaped by meshing its nation-building ideological thrust with pragmatic responses of its regional leadership consisting of former Akalis and Hindu Mahasabhites.

This three-dimensional dissonance, i.e., pronouncements of its national leaders, Sikh leaders and Hindu leaders not only provided the much-needed electoral sustenance, but also exacerbated the existing conflicts.

.png?w=200&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max)