Bilal Ahmad Pathoo

Owner of a houseboat in Srinagar

His family has been in the houseboat business for the past 100 years. But Bilal Ahmad Pathoo, owner of Young Hollywood, is sure that the past three years, including the Covid period, were the toughest over several generations. Thanks to the lockdowns (pandemic), shutdowns (Article 370-related) and breakdowns (lack of travel), Bilal spent most of the past 24 months idling away on the deck of his houseboat at the Golden Lake area. “There is no work. We are frustrated due to growing poverty, but most of us cannot talk about it,” he laments.

The saving grace is the close-knit community of houseboat owners and shikara-wallas. “We have people settled across the globe. They contribute to self-help groups that provide food and other items to us,” he explains. There is a saying in Kashmir that no one dies of hunger in the Valley. This is true during the current crisis, but there are other pressing problems. Houseboats and shikaras require repairs and maintenance. The power department sent electricity bills of Rs 2 lakh each. “Instead of rebates promised by the government, it wants us to pay them when we don’t have money to buy food,” says Bilal.

Bilal, who took a bank loan to look after his immediate family and pay off a debt, is heartbroken about his professional relationships. He employed eight people at a salary of Rs 6,000 to Rs 8,000 each. “They were part of the family, but I had to ask them to leave,” he says.

ALSO READ: Shuttered & Shattered

“I couldn’t retain even one.” He hopes his nephews and other youngsters study hard and move out of this place. “They shouldn’t be part of our sinking boats and houseboats,” he says. As it is, a number of shikara owners have switched to selling fruits and vegetables. Many sold their boats, and the survivors hope to woo tourists with steep discounts.

Naseer Ganai

Narinder Singh 50

Helper at Indian Coffee House, Shimla

Narinder Singh, 50, a ‘helper’ at Shimla’s Indian Coffee House, had never felt so helpless. In pre-Covid times, he earned Rs 14,500 a month, and considered himself a rich man. He sent half of his earnings to his family in Pauri Garhwal, Uttarakhand, and saved money after meeting his living expenses. The father of three—a daughter in college, and two school-going sons—hasn’t been paid for the past 10 months. His manager paid him a paltry one-time sum that wasn’t enough for a single meal a day. His friends and neighbours fed him.

In November 2020, when he went home to Pauri, his pockets were almost empty. He was scared about the kids’ demands—shopping, eating out and visits to markets. “My wife handled it deftly. She convinced the children not to make unreasonable demands. Surprisingly, the opposite happened. My daughter gifted me a mobile phone she purchased from her pocket money,” recalls Narinder, his eyes welling up. The daughter calls him regularly, and assures him, “Papa, you sacrificed a lot for us. Don’t worry about us; we will sail through the crisis.”

Narinder’s 75-year-old mother gets a pension on behalf of her late husband, who was in the postal department. His wife is a MGNREGA worker. He used his PF (Rs 47,000) and got Rs 10,000 from LIC—just about enough for his family to scrape through. Life is tough and it is difficult to make ends meet at two locations. Narinder abandoned plans to repair the parental house and buy his son a bicycle. His biggest worry is how he will marry off his daughter. There is nothing left—no savings, PF, LIC or bank balance. And the Indian Coffee House may close down forever.

Ashwani Sharma

Akshita Arora 54

Mumbai-based actress

Akshita Arora, a 54-year-old Mumbai-based actress, has 60-65 movies in Hindi and regional languages, apart from a slew of TV serials, under her belt. When the first Covid lockdown was clamped down last March, she was in the midst of a serial, Barrister Babu. The producers asked those in the vulnerable age group of 50-plus to stay home, and she was without work for months. Her three children—two sons (an assistant director and a chef), and a daughter—lost their jobs. “It was a difficult period, and we have not recovered from it. Our woes were compounded by the steep price rise of essentials. It was a double blow,” she remembers.

ALSO READ: Why We Feel Poorer?

She sold off her jewellery, the family used up its savings, and she took loans to make ends meet. She is neck-deep in debt. Stars like Salman Khan and Akshay Kumar gave Rs 2,000 to Rs 3,000 each, once or twice, to help mid-level actors. “But how can we survive on such a pittance?” In pre-pandemic times, friends and colleagues helped each other, but then people began to think of themselves due to the uncertain future. She philosophises that one cannot blame them. People think actors earn a lot, compared to technicians, but this isn’t true. “Only we know how we survived during the lockdowns,” she says.

Unlike superstars, who earn astronomical money, character artistes are paid Rs 2,000 to Rs 5,000 a day for a 12-hour shift. The Cine and TV Artistes Association (CINTAA) has an insurance policy for accidents and illnesses. There is no pension or little option for the elderly actors. It does not help to recover dues. “I did a serial in 2012-13, and the producers owe me Rs 2.5 lakh. Had I got that money, I would have been in a better situation,” she explains. A single mother living in a rented house, she feels she may have been better off if she owned a house in Mumbai. Now, she has resumed working in a show, Apna Time Aayega.

Giridhar Jha

Anurag Katriar

Director, Indigo Hospitality

It is ironic that Anurag Katriar aka AK, who is a Director of Indigo Hospitality and operates several iconic F&B brands such as Indigo, Indigo Delicatessen, Tote on the Turf and Neel, whiles away his time playing home chef. Loss of revenue, slash in workforce and resource crunch forced him to stay at home in Mumbai. To keep his family’s spirits high, he tells his son: “Today, you and I will cook grilled chicken with mashed potatoes.” This, he says, gives the child a sense of purpose, as kids tend to get bored, especially when they are forced to stay indoors.

ALSO READ: Covid Rebranded Our Lifestyle

However, there is another reason to become an occasional cook. Zero earnings over the past year pressured him to cut costs. The family has stopped eating out—even during weeks when the lockdown was lifted—and has almost stopped online orders. “We are home, so there is no shopping and travel. I was conscious that I had to cut down on personal expenses, and still maintain a basic lifestyle,” explains AK. This is because he hates debts. So, even the one-time, but large, purchases are out. “We had to buy a new car as the old one went under during the monsoon. It is on hold. I feel it is unnecessary.”

The pandemic struck restaurants hard. Some turned into delivery and cloud kitchens. It’s a low-margin business, and helps the owners keep their heads above water, and the brands alive. AK says most of his staff are gone—except the chefs who get full salaries and those in the corporate office who earn truncated pay because they work from home. He paid them their dues, and advised those he retained to be careful and spend only on essentials. “Even after business reopens, I don’t think we will achieve 50 per cent capacity,” he says.

Lachmi Deb Roy

Mohammed Parvez 35

Runs a brass-welding shop

On a busy day 15 months ago, Mohammed Parvez, 35, who runs a brass-welding shop in his Moradabad home and hires four skilled people, could earn Rs 500 a day. Then Covid barrelled in and he now barely makes Rs 300—and only when there are orders, which is rare. On most days, Parvez and his workers take turns so that each one can earn enough to feed their families, and meet basic needs. His father’s earnings from the dhaba he runs has dwindled by half to Rs 5,000 a month. Income constraints forced Parvez to borrow from relatives and friends. This year’s Eid was low-key—the family had no money to buy new clothes.

Normally, just before Eid, big businesses clear pending orders knowing most workers would go on leave. This turns out to be a big boon for ancillaries and sub-vendors like Parvez. But this did not happen in 2021. In fact, things picked up early this year. By April, though, business was down to a trickle before it came to a halt due to the second Covid wave. The overall financial crunch across sectors implies that payments across the board are delayed. “The process is interlinked. Any delay in payment to units that engage our services means a longer wait for us…by a week or more,” he explains. In addition, the price of brass went up by Rs 100 a kg since March.

Lola Nayar

Asif Rahman 54

A carpet-manufacturer

Asif Rahman, 54, a carpet-manufacturer in Gurgaon, feels his son is more adversely affected by the Covid-induced restrictions than anyone else in his family. A football player, the son captained India in the Asia Cup. “Now, he goes to the field at 5 am every day, and plays by himself,” says Asif. On the whole, the family, including wife and daughter, doesn’t shop, eat out or go to cinema. They work from home. There are so many less avenues to spend on these days. “We have adapted to a new lifestyle by spending more time at the dining table,” he confides.

Business, as anyone can guess, is down. A fancy client list doesn’t matter. Asif’s carpets adorn offices at the White House, Google, NASA and Pentagon; hotels under different banners such as Louis Vuitton (Paris and Cairo), Taj, Hyatt, Hilton and Marriott; retail spaces owned by Ratan Tata, K.P. Singh and Oman’s billionaire Mohammad Al Zubair; and the personal yacht of the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi. “It is challenging. Some of the best-skilled weavers who were with us for 16 years went home. We faced losses in our factories in Varanasi and Agra. Business came to a standstill,” he explains.

Despite the financial crunch, Asif paid his workers and weavers. With a lump in his throat, he says, “Many were infected with Covid. We arranged hospital beds, oxygen and medicines. We went through sleepless nights, so that they survive. We kept paying our employees so that they shouldn’t feel they were out of work.” Clients like Versace were supportive due to long-term business links, but others cancelled their orders. It was a double whammy—income dried, many costs remained. “Now, we are trying to keep our nose above the water,” he says.

Lachmi Deb Roy

Agnes Lyngdoh Talukdar

Owner of a beauty parlour

A regret that continues to gnaw at Guwahati-based Agnes Lyngdoh Talukdar for more than a year is the pain and anguish she felt when she handed pink slips to two of her employees. The owner of Agnes’s Beauty Parlour, established in 1986 and which she claims is the second oldest in the Northeast, adds: “Though they were good, I couldn’t help it because it was difficult to run the business.” She retained five. “They are with me for so many years now, and I cannot see them go, no matter what difficulties I face,” she explains.

At a personal level, the loss of income made her miss out on EMIs on bank loans. “There was some relief last year when the RBI declared a moratorium on repayments, but now nothing is clear, and I am unable to pay.” The family’s predicament is accentuated by her husband’s loss of income—a gym owner whose business was idle for months. “Things might have been somewhat different had there been salaried members in the family because that would have ensured some steady income. At my advancing age I cannot think of diversifying, and there’s no guarantee that a new venture will not suffer the same fate,” she says.

Beauty parlours and gyms were among the last businesses to open after lockdowns. “When we did reopen last year, we rarely got a full house because customers were wary. Besides, facials and threading were off because these require closer contact,” she says. During the second wave, the parlours could open briefly with shortened timings. “There’s no point opening for an hour or two because we cannot earn enough to cover overheads. Our employees come from far and wide. They have to leave home early before the curfew kicks in. It is terrible,” she says. She hopes for the good old days to return. And yes, she wants to rehire the two employees she had dismissed with a heavy heart.

Dipankar Roy

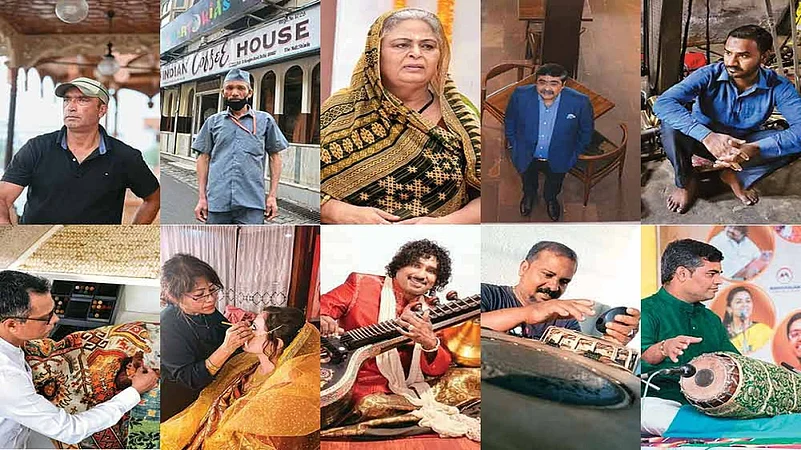

Veena player Thiruvaiyaru S. Swaminathan

The Dirge Drags On

Trust a virus to turn a vivace into an elegiac cry. Mridangam player M.S. Venkatasubramanian struggles to recall when he last performed at a concert, in front of an audience. He gets the years mixed up before remembering it was in February 2020—he accompanied a vocalist at the R.K. Padmanabha Festival in Bangalore. “Actually I hoped 2020 would be better than 2019, when I had 129 concerts. I normally clock 150-200 a year,” says the 37-year-old professional from Tamil Nadu who has 16 years of concert experience. But COVID-19 and the lockdowns killed his hopes that would have included a couple of money-spinning trips abroad. Venkat, as he is known in the music circle, stared at a bleak future as his annual income of Rs 3 lakh dried up. The monthly rent of Rs 20,000 for his two-bedroom flat in Chennai became a formidable challenge. “I knew that our landlord depended on it to run his household. I somehow managed to pay it. Otherwise I had to dip into my savings. Students did not show up due to the fear of getting infected, and this meant a loss of Rs 50,000 a year on tuition. While vocals or stringed instruments can be taught online, percussion requires in-person coaching,” he points out.

Sowri, a mridangam maker

Even in Thanjavur and neighbouring districts, considered to be the cradle of Carnatic music, the professional scene spread across temples, mutts and village festivals took a big hit. Thanjavur-based veena player Thiruvaiyaru S. Swaminathan found that about 50 concerts lined up for 2020 were clipped. “Temple concerts attract the biggest audience and we get decent money. With temples closed and festivals cancelled, even non-Chennai artistes like me suffered,” says Swaminathan, an MPhil in music.

While the curfews and quarantines hit everyone, the top- and middle-level artistes managed with online classes and bespoke subscription-based online content. “Even the top 50 accompanying artistes on violin and percussion kept themselves busy. Those badly hit are the mid-level and smaller percussion players, who accompany the main musicians and play for dance recitals,” explains Thanjavur K. Murugaboopathi, a top mridangam player. Seeing their plight, he and fellow musicians formed the Global Carnatic Musicians Association (GCMA), a collective that raised funds to assist the suffering musicians. “We collected Rs 55 lakh and supported 1,400 artistes for over six months with a monthly allowance of Rs 5,000 each,” says Nirmala Rajasekar, a Minnesota-based veena player who spearheaded the fund-raiser in the US. “We specifically covered nadaswaram and thavil players, who were worse off since weddings, their main avenue of earnings, were abridged, if not cancelled.” She says a fresh round of financial support for 2021 is on because of the second wave that nixed concerts again.

Mridangam player M.S. Venkatasubramanian

Those in the ecosystem that supports the musicians suffered immensely, including mridangam makers and repairers, who are like extended families of the percussionists. They were pushed to penury after orders dried up. Even regular servicing of instruments ahead of concerts didn’t happen. “From August onwards, we used to get new orders, repairs and tuning ahead of the December music season. Before Covid, I earned Rs 45,000 a month. I am now unable to pay my daughter’s college fees despite the GCMA money,” discloses Sowri, a mridangam maker in Mylapore. At least 20 families in Chennai were badly hit. “There are at least 100 families involved in making veenas and another 100 make percussion instruments in Tamil Nadu,” says Lal of Saptaswara Musicals, a top musical instrument dealer in Chennai. “There are instrument makers in other southern states. We normally witness brisk sales ahead of the December season, and take orders from foreign students. But the lockdown and travel restrictions meant that 50 per cent of our businesses suffered. We hoped to have a normal season in 2021, but the second wave raised serious doubts about it.”

G.C. Shekhar in Chennai