The Trade-Off

India’s imports from China

- $68.34 billion in 2019

- $58.70 billion in 2020

India’s exports to China

- $17.27 billion in 2019

- $18.92 billion in 2020

***

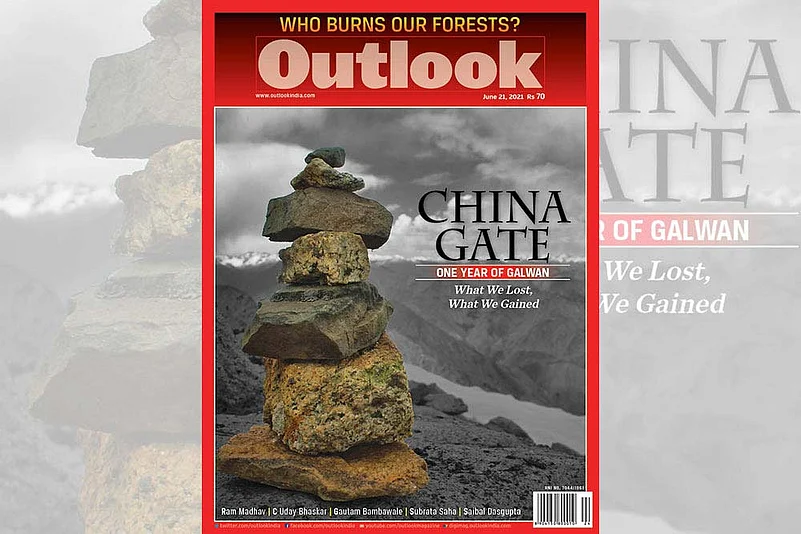

A year after border clashes between India and China in Galwan Valley, and the subsequent Indian campaign to boycott Chinese goods, trade between the two countries has taken an unexpected turn. China is buying more from India than it did before, while Indian imports have come down sharply. But this may not be because of the campaign to boycott Chinese goods, or Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s signature Aatmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan for import substitution. India’s imports from China have fallen significantly—from $68.34 billion in 2019 to $58.70 billion in 2020, a year when the coronavirus pandemic has ravaged the global economy. The sharp decline in imports may indicate the drive to boycott-China and Make in India was having an impact. But the $10 billion question is: has Aatmanirbhar Bharat resulted in the sharp reduction in imports?

ALSO READ: Infernal Affairs

Analysts say that’s not really the case. Even pro-BJP forces behind the campaign to boycott Chinese goods, like Swadeshi Jagaran Manch (SJM), are not celebrating. “We recognise it’s a difficult task to replace imports of Chinese goods. Our factories have become too dependent on Chinese imports for nearly two decades. But changes are taking place. I would say the government is on the right path,” SJM national co-convener Ashwani Mahajan says. It is apparent the government made little effort to enforce the boycott of Chinese goods beyond a handful of sectors such as telecommunications. This is partly because it would have been dangerous to disrupt Indian industry when it was weathering the challenge from Covid.

ALSO READ: Checkmate & Stalemate

Government-driven reduction in imports is largely in telecommunications, electronics and media sectors, which have been red-flagged by New Delhi for national security reasons. One of the biggest impacts was seen in the import of electric integrated circuits and micro-assemblies, which declined 17.5 per cent to $2.92 billion. Another area is radio broadcast and reception equipment, purchases of which fell 45 per cent to $344 million. India’s import of electronic integrated circuits and many intermediates from China has declined, either because of lower demand or import substitution. In fact, import of electronic integrated circuits (HS code 8542) witnessed the sharpest fall in 2020-21. Yet, during the pandemic, India also imported huge quantities of other electronic items, automatic data processing machines, mobile phones, medical equipment etc. Actually, fall in imports—in diodes, transistors and semiconductor devices—was only 5.36 per cent to $1.56 billion. Clearly, the government does not want to come in the way of imports that are essential to industry, and those they cannot replace in a hurry.

ALSO READ: Plateau Of Bad Faith

It is significant that import of essential medical items went up sharply during the Covid lockdown, as did the trade in internet peripherals. “During the pandemic, India imported huge quantities of electronics goods, automatic data processing machines, mobile phones and medical equipment,” says Prabir De, author and professor at Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS). “Trade between these two large emerging markets is yet to pick up the desired momentum due to security threats,” he adds. The Rs 12,000-crore Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme launched in April 2020, which was extended to several sectors in November 2020, is already having an impact on factory floors, he informs. Manufacturing firms are encouraged to improve and enhance production in sectors such as food processing, automobile components, pharmaceuticals, battery storage and speciality steel.

ALSO READ: ‘This Apathy Breaks My Heart’

There are serious limitations in what Aatmanirbhar Bharat could do in the short span since November 2020 when the PLI scheme—the focal point of the plan—was extended. Analysts say the reason for the sharp reduction in imports could be found in the long months of a nationwide lockdown to check the spread of the coronavirus, which resulted in diminishing demand for Chinese goods both in the retail market and in factories. This is also evident in the fact that India’s overall imports from across the world fell from $479.90 billion in 2019 to $368 billion in 2020. The pandemic year saw India’s overall imports declining to the lowest level since 2017. In case of China, it is the lowest since 2014.

In fact, it can be said that the pandemic and its adverse impact on business was another reason why Aatmanirbhar Bharat did not take-off in full force. “If you look at the data, major decline in imports from China are in industrial inputs, including electronics and electrical, due to factories in India that were closed or working partially,” says Mohammed Saqib, secretary general of India China Economic and Cultural Council. The effect of the lockdown and low sales was evident in lower purchases of several goods from China. Two items— paper boards and footwear—saw a fall of 63 per cent in imports from China. Purchase of textile fabrics also came down by 49 per cent, while imports of pumps and fans slowed 22 per cent to $666 million. Cost of sea transportation has also risen sharply, which contributed to the fall in demand for Chinese goods in the retail sector.

ALSO READ: ‘We’re Proud Of The Bihar Regiment’

One of the biggest advantages of the slide in imports and rise in exports of Chinese goods is the sharp 22 per cent reduction in trade deficit in 2020—from $51.07 billion to $39.78 billion. This comes after decades of India complaining about low Chinese buying and high trade deficit.

Export Scenario

Indian exports have risen by $1.65 billion to reach $18.92 billion in 2020. But this is no cause for celebration. China is still not buying important, value-added industrial products. Instead, it continues to treat India as a source of low-priced raw material—minerals and semi-finished goods. There are serious questions on whether this is merely a business issue or a sign that Beijing’s political leadership does not want to give India the status of a competing industrial economy. Indian exports to China showed tremendous performance, growing from $17.27 billion in 2019 to $18.92 billion in 2020—a rise of 9.55 per cent. This is a sterling feat if one takes into account the fact that China is usually reluctant to buy Indian goods and eager to push its own products into the Indian market.

ALSO READ: Beard The Lion To Bell The Cat

But a close look would show the Indian performance is not all that flattering. Indian exports have grown in the area of raw and semi-finished materials, which give Indian companies little advantage in terms of value addition. This includes a dramatic 149 per cent rise in export of cotton and metals like pig iron and semi-finished iron and non-alloy steel products rising by 238 per cent and 914 per cent, respectively. Another example of India selling its raw materials and semi-finished goods is the 119 per cent growth in refined copper and copper alloys.

ALSO READ: Asymmetry Of Threat Management

If the Aatmanirbhar Bharat campaign had really worked, the impact in lower imports would be to the extent of 30 per cent, experts assert. The remaining 70 per cent reduction in Indian imports was caused by low demand during the pandemic. Indian imports might go back to where it was before the pandemic, once markets and factories fully open, and demand for Chinese goods begin to rise. The rise in exports might be a short-lived affair because Chinese industry is stocking up resources at low prices and might decide to cut down on imports from India in later years. In other words, India has little option but to make exportable, high-quality goods and find ways to replace imports.

ALSO READ

(The writer is a senior journalist who has reported from China for many years. Views expressed are personal)