Justice Krishna Iyer was elevated as a Supreme Court judge on July 17, 1973, shortly after the appointment of Justice A.N. Ray as the Chief Justice of India, superseding three senior-most judges. Justice Iyer’s appointment was made by the President after consultation with the Chief Justice of India following the mandate of Article 124 of the Constitution, before the advent of the collegium system. His appointment to the Supreme Court evoked strong opposition from legal circles, especially the Bombay Bar led by Soli Sorabjee. Ideological objections were at the heart of this opposition—after all Justice Krishna Iyer was an avowed communist. He had practiced as a lawyer and become a minister in the communist government in Kerala. His acquaintance and friendship with Mohan Kumaramangalam, the powerful Union minister for steel and mines was well-known. After completing three years’ tenure on the bench of the Kerala high court, he was appointed as a member of the Law Commission of India in September 1971.

The presence of Justice Krishna Iyer in the Supreme Court literally transformed the institution. During his time on the bench, the court increasingly became concerned with the poor and the under-privileged, especially those who could not even afford to have access to justice despite being subjected to gross injustice. His concern for rule of law and human dignity gave rise to a new jurisprudence which was pro-poor, pro-downtrodden and pro-marginalised.

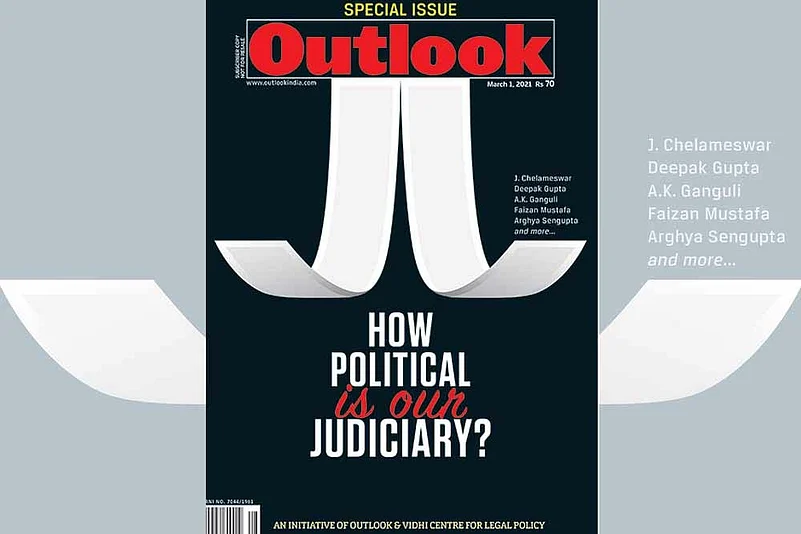

ALSO READ: Free Or Fettered?

In the context of compulsory acquisition of land belonging to small holders, he had observed: “It is fundamental that compulsory taking of a man’s property is a serious matter and smaller the man, the more serious the matter.” Emphasising the significance of criminal justice, even with regard to the prisoners and convicts, he had observed: “Karuna (compassion) is a component of jail justice. Basic prison decency is an aspect of criminal justice.” The most significant reforms in prison administration in India came as a consequence of his crusade. It is difficult to imagine if under the prevailing system of appointment of judges by the collegium, a boldly ideological judge like Justice Krishna Iyer would have ever made it to the bench of the Supreme Court.

Neither, perhaps, would a former CJI Sabyasachi Mukharji have ever been appointed. An anecdote about his appointment summarises why. As the senior-most puisne judge in the Calcutta high court, he had passed certain interim orders in a writ petition. A challenge from those interim orders was made before the Supreme Court. An SC bench consisting of Justices D.A. Desai, A.P. Sen and Baharul Islam passed an order requesting the writ petition to be placed before Justice Mukharji for hearing and for pronouncement of the order the next day. Though commonplace today, such an order from the Supreme Court, that directed high courts on how to list matters (the next day) and when to pronounce the order (the same day) was viewed as an erosion of administrative independence of the high court and the decisional independence of the judge presiding over the case. Though Mukharji complied with the order, he said in his judgment: “The contents and mode of communication to this court were unprecedented. In my opinion, the aforesaid communication was unwarranted by the Constitution, law and precedence. As the dignity of this court was concerned, I was hesitant to act on the said communication.”

ALSO READ: The Supreme Court A Long Political Journey

Despite this plain-speak by a mere puisne judge of the high court to the mighty Supreme Court, Justice Mukharji was elevated to the Supreme Court by the President, in consultation with Chief Justice Y.V. Chandrachud. Justice Chandrachud staved off pressure from his colleagues, who had presided over the bench hearing the appeal from Mukharji’s orders to make the recommendation. Mukharji would go on to serve as the Chief Justice of India. It is, again, difficult to imagine such an outspoken high court judge making it to the Supreme Court today, let alone serving as Chief Justice of India.

Appointment of judges to the superior courts had been a matter of great concern even for members of the Constituent Assembly, for they knew that a democratic society and the rule of law that the Constitution envisaged could be achieved only if independence of the judiciary is secured. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, while explaining the scope of the constitutional provision regarding appointment of judges in the Supreme Court, had cautioned members that while independence of judiciary was a must, “we do not want to create an imperium in imperio” and with that end in view, provided that the judges be appointed in consultation with the Chief Justice of India. Though the Second and the Third judges’ cases referred to those observations of Ambedkar, they departed from their spirit. Thus, emerged the collegium system, an entirely judge-made law that arrogated to the judges themselves the power of appointing their brethren.

Even before the NJAC was passed by Parliament, in a public interest litigation initiated by private trust Suraz India, the legitimacy of the collegium and the primacy accorded to it in the Second and Third judges’ cases were questioned. The primary question before the Court was whether the Second and Third judges’ cases have nullified Article 124 of the Constitution as the President has no power to consult other judges of the Supreme Court, in addition to the Chief Justice of India, while appointing judges to the court. I was appointed amicus curiae by the court and it was so important a question that the two-judge bench referred the matter to a larger bench. Ironically, the three-judge bench simply dismissed the matter on the ground of lack of locus standi of the trust.

Even in the NJAC case, the five-judge bench which underlined the primacy of the collegium system, though it reproduced the issues raised in the trust’s case, did not find it convenient to deal with those issues.

Today, the Supreme Court, despite comprising fine judicial minds, has lost the stature it enjoyed in the last century. Judges like Krishna Iyer and Mukharji, different in their own way yet unrelenting in their courage of conviction, can scarcely make it through the considerations that undergird collegium recommendations and their acceptance by the government today. As a result, the country is deprived of genuine judicial wisdom. Krishna Iyer’s words in the Kamgar Union case are even more apt today: “In a competition between courts and streets as dispenser of justice, the rule of law must win… and wean (the aggrieved person) from the lawless streets”.

It is no surprise that protests on the streets continue as the Krishna Iyers of our judicial fraternity remain conspicuously absent from the bench. In order to seek out the best women and men from the bar and the high courts to serve on the Supreme Court, one hopes that the new generation of judges would have high on their agenda reforms to the collegium system.

(Views expressed are personal)

ALSO READ

Amal K. Ganguli Senior Advocate in the Supreme Court