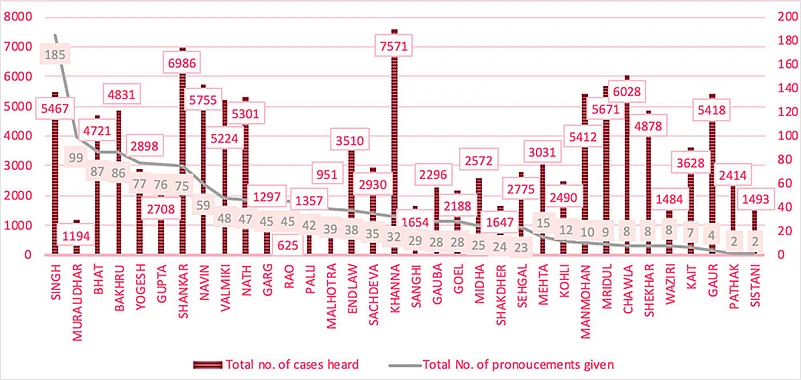

- 1,194 Cases heard

- 99 Pronouncements

***

Recently, in an unprecedented move, the Supreme Court collegium withdrew its recommendation to make an additional judge of the Bombay High Court a permanent one. The withdrawal followed two decisions by the Bombay High Court judge which, in addition to being bad in law, were publicly criticised by scholars and practitioners alike. The jury is still out on whether the collegium was right in intervening in the way it did. However, what transpired does point to a larger systemic problem—the absence of a performance evaluation mechanism for India’s higher judiciary.

While the district judiciary is subject to periodic assessments through a system of ‘Annual Confidential Reports’, no such system is in place for the higher judiciary; even though judicial performance evaluations (JPEs) have been regularised in other jurisdictions. Interestingly, the judiciary under the eCourts Project, which aims to ensure Information and Communication Technology (ICT) enablement of the judiciary, has introduced the Justis application to help judges evaluate their own performance. However, there is not enough information to determine its inner workings or extent of use. Therefore, even though the judiciary might be in possession of the required data, the lack of performance evaluation systems compromises the legitimacy of collegium recommendations and the faith that the public has in the judiciary as an institution.

ALSO READ: Free Or Fettered?

In the past, the Indian judiciary has been resistant to enforcing performance standards. In 2001, Madhu Trehan, then editor of the Wah India magazine, sought opinions from lawyers to evaluate judges of the Delhi High Court on parameters such as integrity, understanding of the subject and others. The magazine published the scores adjacent to photographs of the judges. In turn, the HC initiated criminal contempt proceedings against Trehan. She was forced to issue an unconditional apology and take down the article. The judicial brouhaha over the magazine’s article, however, doesn’t discount the fact that the introduction of such a mechanism for performance evaluation of the higher judiciary is long overdue, and given such precedents it is important that the evaluation mechanism is thoughtfully crafted.

Justice S. Muralidhar.

A Case Study Assessing Performance of the Delhi HC Judges

An example of how JPEs reflect on the performance of judges is highlighted in a study conducted by the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy of Delhi High Court judges. The results of the study found, in 2018, that out of the 34 judges who held court throughout the whole year, some performed better than others. The study scraped data from the Delhi HC website to compare the number of cases heard and the number of unique judgments pronounced, as seen in the pronouncement cause list.

ALSO READ: The Supreme Court A Long Political Journey

It was found that judges who heard a large number of cases did not always pronounce more judgments. This variance could be a result of judges simply not authoring judgments or their resistance to hear complex cases that require judgments to be pronounced. Alternatively, judges could be inclined to dispose cases through interim orders or the rosters themselves could be poorly and unequally organised. Finally, given limited data available, the methodology might leave some judgments, such as daily orders, from being included in the data-set.

A contrary example was found in Justice S. Muralidhar’s disposals. A study of his roster revealed that he primarily listened to cases like criminal appeals, death sentence references, criminal leave petitions and criminal writ petitions. Since disposal of these cases requires appreciation of facts and considerable amount of judicial time, the number of cases that were heard by him was comparatively lower. However, a large majority of those cases translated to final pronouncements, thereby, showing a good performance score. Contrastingly, other judges did not perform as well and might have chosen to hear cases such as criminal miscellaneous cases, which require considerably lesser judicial time.

In June 2019, a sitting judge of the Madras High Court, Justice G.R. Swaminathan, released statistics with regard to the number of cases he had disposed since he assumed office. This was, ostensibly, to affirm his commitment to judicial accountability. Justice Swaminathan’s move should have encouraged other judges to embrace self-assessment of performance, which can become a feature of the overall evaluation mechanism as well.

ALSO READ: Collegium Collateral Damage

JPEs, whether conducted by external actors or by judges themselves, will benefit judges by nudging them towards improvement. They can help judges identify bottlenecks, areas of improvement and even involve civic society in coming up with targeted solutions. The system will benefit from greater transparency and accountability. Such evaluations can provide insights into how rosters are organised and help disclose rationales for why some cases are afforded higher priority and dealt with greater urgency than others. In turn, such disclosures can make the chief justices, who organise the rosters, and the judges, who execute them, more accountable to themselves, each other and the public. In terms of appointments, they are also likely to provide better insights into the decision-making process of the collegium and highlight deviations that do not correlate to good performance.

It is incumbent on the judiciary to craft an evaluation mechanism that combines both qualitative and quantitative indicators of performance. Along with case clearance rate, disposal data, time spent to dispose cases, it is equally necessary to assess the quality of judgments, administrative efficiency to organise rosters and performance within administrative committees. To be able to conduct JPEs in the future, it is necessary that judicial data is made publicly available in an organised manner. It is desirable that the judiciary identify ways to improve the quality of data available on National Judicial Data Grid and other public websites.

Embracing performance evaluation is also an opportunity for the judiciary to re-instil the waning faith in the institution. Given the new blitz that the judiciary has seen in the media over the past few years, judges tend to come into the limelight only when they deal with high-profile cases. Even in such cases, the focus is often on the outcome of the specific case and its palatability to a wider audience. These headlines tend to block out the performance of judges who critically examine cases and dispose them. India does have well-performing judges and the country should know as much through a transparent performance evaluation mechanism adopted by the judiciary.

(Views expressed are personal)

ALSO READ

Vaidehi Misra and Chitrakshi Jain are research fellows with Justice, Access and Lowering Delays in India initiative at the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy