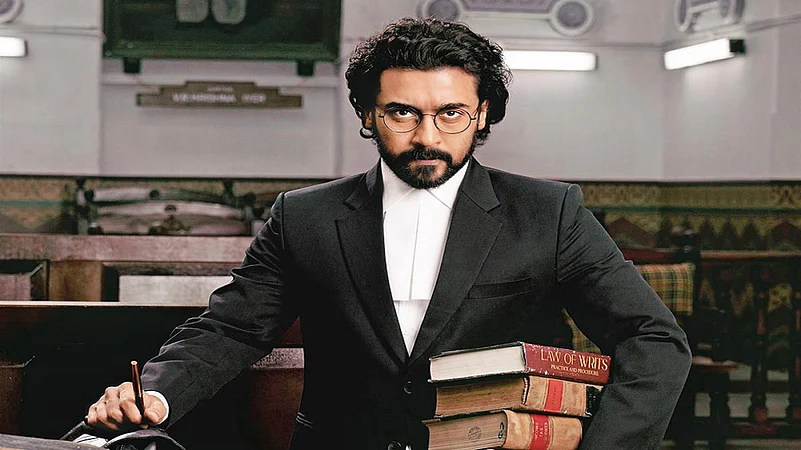

When the Suriya-starrer Jai Bhim released on Amazon Prime on November 1, it was greeted with universal praise, with the film climbing to the top spot on IMDB, and everyone rushing to congratulate the team. Titled after the popular Ambedkarite greeting, the movie held the message that justice was possible by keeping faith in the constitutional framework. Coming from a film industry which routinely celebrates uber-masculine lone-wolf policemen and their extra-judicial excesses, Jai Bhim was exceptional in its unflinching portrayal of police brutality against the Irulars, an oppressed tribe.

It was difficult to foresee that movie running into trouble with the Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK), a caste-based party that represents the Vanniyar community in north Tamil Nadu. PMK’s heir apparent Anbumani Ramadoss sent a lengthy letter to actor Suriya with a set of nine questions that claimed the movie had portrayed Vanniyars in a poor light. One of PMK’s bones of contention was that the police officer who brutally tortures Rajakannu (the falsely accused) was named Gurumurthy in the movie. The implicit suggestion was that Guru referenced ‘Kaduvetti’ Guru, a recently deceased PMK strongman known for his anti-Dalit rabble-rousing. Another issue which has occupied much bandwidth around this controversy is the wall calendar which appears in the scene where Gurumurthy makes a call from his home. Although the calendar originally portrayed an agni-gundam (a pot containing fire), it was digitally altered the following day to display a calendar carrying the image of goddess Lakshmi.

Vanniyars trace their origin myth to being born out of the cauldron of fire (thee-satti/agni-gundam). This fire-cauldron is the symbol of Vanniyar Sangam, the caste association and parent-body that birthed PMK. I have seen this icon emblazoned on yellow t-shirts of young men in the northern belt, an unspoken caste-assertion. Anbumani Ramadoss himself sports a tattoo of this agni-gundam on his right forearm. The cauldron is an uncanny symbol, especially in light of the political violence that has often involved setting Dalit settlements on fire, most horrifically witnessed in Dharmapuri (2012).

This agni-gundam has been pivotal in enabling the construction of Vanniyars (themselves considered Shudra) as a warrior race, and to legitimise their claims to self-identification as Kshatriya, within the four-fold Varna system. However, much of this outrage holds no import because the scene containing the agni-gundam was replaced on the second day of the film’s release, even before any statements were made. Following Anbumani’s lengthy letter, the Vanniyar Sangam issued a legal notice to the actor, director and producer of the movie, demanding an unconditional apology and Rs 5 crore in damages. Further, the outfit also appealed to the Directorate of Film Festivals under the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, to not consider Jai Bhim for any appreciation or recognition. Things also took an extreme turn with incitement to violence. PMK’s Nagapattinam district secretary Sithamalli Pazhani Swamy announced a cash award of Rs 1 lakh to any youngster who attacks actor Suriya, while PMK’s Salem MLA R. Arul wrote to theatres in Salem asking them to stop screening Suriya’s movies. Meanwhile, Tamil Nadu Police offered protection to actor Suriya’s home. In an interview on Galatta.com, the son-in-law of Kaduvetti Guru made an open threat that theatres would be burnt. An open challenge was thrown to the police force: what can five armed policemen do in the presence of a mob of 10,000 people? In another video, Kaduvetti Guru’s son Gokul openly threatened journalist Savukku Shankar, saying: “If a head, hand or a leg goes missing tomorrow, nobody should come in search of us. This is our message to the police. Tomorrow, if something untoward happens, we request anyone not to come in search of us.” Finally, on November 21, Jai Bhim’s director T.J. Gnanavel issued a two-page statement saying the movie did not have the slightest intention of hurting or causing offense to any individual or community. He also offered apologies if anyone had felt offended or hurt. Hopefully, this shall put a full-stop to the controversy.

ALSO READ: 'Hum Dekhenge': Times When India Protested

Why did the PMK choose to make a mountain out of a molehill? There are several motivating factors: to stay relevant and in the spotlight. To lay claim to the mantle of victimhood even as dominant castes victimise others. Most of all, to consolidate a dwindling voter base.

The fall in PMK’s vote share has been a decade-long phenomenon. In 2011, the party won only 3 of the 30 seats it contested. In the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, as part of the NDA alliance, it won a sole parliamentary seat. In 2016, contesting independently in all 234 assembly constituencies with Anbumani Ramadoss as the proposed CM candidate, the party drew a blank. In 2019, the party again failed to win a single seat out of the seven parliamentary seats it contested. Even on the back of successfully forcing the AIADMK government to implement 10.5 per cent internal reservation for Vanniyars, the PMK could win only five of the 21 seats it contested in the 2021 assembly polls. The low hit-rate also signals that Tamil Nadu voters might not be completely subsumed by PMK’s manipulative social engineering formula of consolidating all backward castes against a common Other—the Dalits. Since 2012, Ramadoss has pioneered an effort to create an explicitly non-Dalit political bloc by rallying together dominant backward castes in the state on the common agenda of diluting the SC/ST Prevention of Atrocities Act, and by dog-whistling against love marriages and inter-caste marriages. Ramadoss even told reporters that Dalit men “wear jeans, t-shirts and fancy sunglasses to lure girls from other communities”. PMK’s politics has sought to make Dalit men targets of violence and non-Dalit women subject to extreme infantilisation, monitoring and control. Polarising society against Dalit people in an effort to unite non-Dalit intermediary castes shows how selfish political calculations supersede inclusive democratic and egalitarian objectives.

An equally valid observation by Tamil political commentators is the way two pro-PMK films (both by Mohan G) have been made with the sole intention of humiliating Dalits. Dhraupathi, on the theme of intercaste love marriages, aimed to demonise Dalit men for allegedly luring caste-Hindu women with the false promise of marriage. It also portrayed a full frontal attack on Dalit leadership (there is a character playing a Dalit political leader who bears striking resemblance to VCK president Thol. Thirumavalavan). Released last month, Rudra Thandavam centred on the misuse of Prevention of Atrocities Act; Dalit Christians claiming SC status; and a mother poisoning an errant son to death, thus glorifying honour killings. Quite magnanimously, neither VCK nor Dalits in Tamil Nadu indulged in outrage politics over such unfair and shameful depictions.

Dalit homes—Two-three families, consisting of 20-25 people in one room, is a common sight

Outrage culture is not exclusive to the PMK. Any right-wing outfit or party that finds itself bereft of genuine social issues desperately grabs such limelight-hogging measures. In October last year, BJP took to the streets demanding the arrest of Thol. Thirumavalavan, claiming his statement that Manusmriti considers women as prostitutes had offended and denigrated Hindu women. VCK responded by calling for a ban on Manusmriti, and Thirumavalavan offered to quit electoral politics if it became necessary to resort to such an extreme step to effectively counter Hindutva forces. BJP’s other pointless protests in Tamil Nadu and Kerala include demonstrations against price hike on petrol, diesel and cooking gas—whose primary responsibility rests with the BJP-led Modi government.

In this age of post-truth, right-wing groups rely on creating false content to fuel outrage which it can expect to harvest. Lacking regulatory standards or gatekeeping of mainstream media, social media provides convenient tools to peddle politics of hate. Speeches that last an hour can be clipped and doctored to produce out-of-context hate videos. Writer Salma recently shared on Twitter how one of her speeches was digitally manipulated and clipped by right-wing forces, to show her saying that Muslims did not vote for her. As a Muslim feminist, these efforts by right-wing groups were clearly aimed to foil her popularity among her own community.

The anatomy of hate that proceeds from the creation of doctored content follows a predictable pattern. The News Minute carried a story a few days ago about Harish, a news reporter and two others, being booked in Karnataka’s Kodagu district for allegedly morphing a video of a Muslim woman raising the slogan ‘Ambedkar Zindabad’ to make it appear as if she was shouting ‘Pakistan Zindabad’. Those who morphed this video called for a bandh in Shanivarasanthe on November 15, claiming that Hindus in the area where oppressed. Another accomplice shared this video in WhatsApp groups, with the message: “People from the Muslim community have shouted Pakistan Zindabad in front of the Shanivarasanthe police station. The police must arrest and register a case against these anti-nationals”. Fascism in our time functions in nefarious ways. Recently, a Twitter account which was pushing violent content and rhetoric, while claiming to represent an Antifa organisation, was found to be linked to a white nationalist group.

Political machinations apart, what is unfolding in Tamil Nadu is a right-wing effort to silence freedom of expression. Keeping the Jai Bhim controversy alive for three weeks since the film’s release is an attempt by caste and communal forces to usher in a reign of terror where not only artistes and journalists, but also common people, will not have any space left to express themselves. After what happened with Jai Bhim, which director will find courage and conviction to make a movie on, say, Dharmapuri 2012, where 300 Dalit homes in three villages in retaliation for the intercaste love marriage of Divya and Ilavarasan?

(This appeared in the print edition as "Outrage Politics")

(Views expressed are personal)

ALSO READ

Meena Kandasamy, poet, writer, feminist and dalit activist