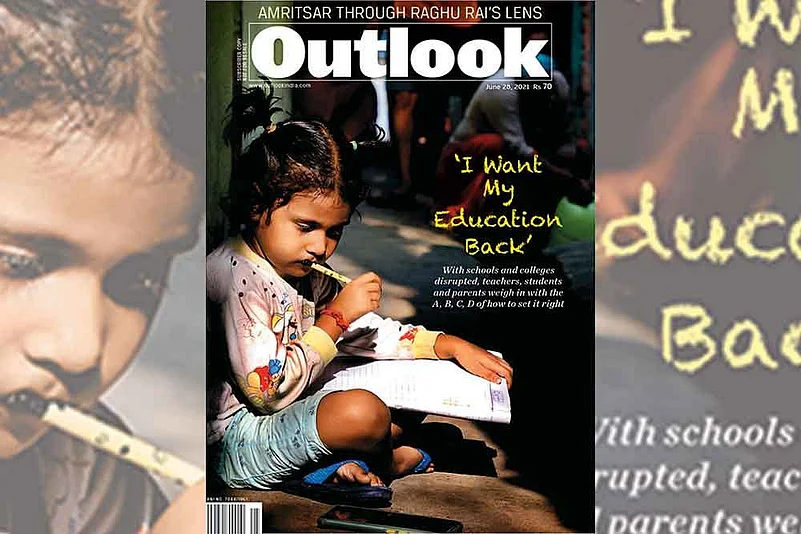

'I was informed about your lectures and classes by my schoolteacher and I am attending your classes since March 2020. Your classes have given me new inspiration and new zeal of life. Thanks is a very small word for the debt I owe you. You have become the light in my life’s darkness and a pillar of strength. I thank you from the bottom of my heart. '

When a hand-written letter reached Sanjeev Kumar in December last year, the 43-year-old teacher based in Punjab’s Bathinda was admittedly moved to tears. Not just by the words dedicated to him but by the sheer poignancy of it all—a simple ‘thank you’ note that captured the predicament of students trapped in an alien world of the Coronavirus across the world. Kumar, a Kendriya Vidyalaya teacher for nearly two decades, has emerged as a hero not only for Anvesha Kole, the letter-writer from Srinagar, but for students as far as Qatar, Dubai and Nairobi.

Kumar, a mathematics teacher, has been imparting online classes for more than 3,500 students daily since March last year, going above and beyond the call of duty to help youngsters cooped up in their homes. He spends about Rs 20,000 per month for his free-of-cost online classes for students of classes 8 to 12. Kumar’s is but just one story in the education evolution in the country that is adapting and adopting newer methods to keep the classes going for students.

ALSO READ: Imagining The Post-Pandemic Campus

But that is only half the story. As the millenium’s deadliest pandemic stretches into the second year and the world ponders how the COVID-19 virus will manifest next, students are grappling with the toughest test of their young life—cut off from friends, from schools, from outdoor activities. Experts have already sounded the alarm over the emotional and physical toll on the young minds and bodies as fatigue creeps in and new social norms become the new normal. Behaviour alteration is pushing their limits. This is the story of every Indian household with kids since schools closed in April 2020.

According to UNICEF, an estimated 1.5 million schools remained shut in India since 2020 due to the pandemic and lockdowns, affecting 247 million children in elementary and secondary schools. What it means is that students have been forced to get their education at homes, glued to their mobile handsets or laptops—basically a one-way street without verbal and nonverbal communication, affecting their social skills and whole lot of other aspects of growing up.

ALSO READ: Flight To The Future

And then there is the even more worrying factor of the urban-rural divide in India.

Only one in four children in India has access to digital devices and internet connectivity. Unfortunately, most of these are in urban India. According to a survey by NGO ChildFund India, around 64% of rural children run the risk of dropping out if not provided with additional support to cope up with learning gaps. India’s education system stuck in the conventional classroom teaching did make an attempt to transition to online classes, creating infrastructure and training teachers to conduct classes on a daily basis. But there are more questions than answers.

ALSO READ: The Interruption As Window of Opportunity

If education experts are to be believed, challenges like learning gaps, social adjustment with peer groups, deeper economic divide and adapting to non-school environment will have prolonged affects, and the only way to overcome them would be more interactive classes and de-emphasising the blackboard lecture-rote learning. And the millions who would have been left behind due to constraints like non-availability of technology will have voids that will haunt lifelong.

Global Classroom

And that is where people like Kumar have stepped in. Across India, many like Kumar are challenging the rampant commercialisation of tutorial education, understanding the economic pain of parents. They are bucking the trend started by coaching institutes and fuelled by India’s start-up ecosystem where parents are ready to dole out any amount for their kids to learn more and stay ahead. Parents are resorting to various free live tutorials being offered by schoolteachers who are trying to beat the Covid blues both economically and intellectually.

In the woods (Clockwise from top) Students in Tamil Nadu enter a forest and a teacher atop a tree in Bengal, all in search of mobile signals; and a teacher in Ladakh conducting online classes.

“I never knew a small initiative could bring in kids from across the world together at a small zoom session. It’s the least I could do for the kids,” says Kumar. “Global classrooms give better exposure and diversity to kids. I do face communication gaps some time, as kids from Tamil Nadu want more English, while those from Uttar Pradesh want more Hindi, but we manage a bridge as maths is all about numbers.”

Teachers accustomed to the chalk and blackboard have suddenly found themselves at a learning curve themselves as they are forced to adopt technology to impart classes. Some have been forced to climb trees in search of wireless signal for the mobile phone and some going around villages, carrying a portable public address system to reach out to students in their homes. Rubber bands and hair clips are holding mobile handsets for some others as they sit down for their daily classes.

“I see intervention of technology in the educational scenario as a huge opportunity. Some teachers who were not able to use it at all have now adapted to it quite smoothly. This pandemic has made everyone, including teachers, students and management, see that intervention of technology in education is very important,” says Bishwajit Banerjee, principal of VidyaGyan Leadership Academy in Bulandshahr.

However, not all, not even students, find online classes too exciting or educational. What they miss is to be with friends. A game of football. Or a discussion over freedom of speech. Falling out with friends and making up after two days. Sharing notebooks and the lunchbox. For Anisha Sathpathy, a second-year B.Com student at Christ University, Bangalore, education is a see-and-feel thing. “Online education is out of compulsion. Reading chapters and just listening to teachers is not what education is. When we are in school or college, observations are a big part of our learning and understanding. There is a different kind of comfort level in schools and colleges which I don’t feel in online classes.”

Pune-based Mradula Singh, mother of two teenage girls, also feels that distant learning can work well for younger kids and that’s only if both the parents are not working. She says, “The system itself needs a thorough rethinking in the current situation because schools have overcome the technology fear; it is time to innovate teaching, adopt new tools and work with children in a more informal way. After a year, we still see children sitting in front of their screens, due to parent’s presence, sleepily watching slides of textbooks or listening to lectures without interest.”

Rural vs Urban

Punjab might have found a solution to the dilemma: school or home? Raminder Kaur, a teacher at a government school in a village in Hoshiarpur, says rural schools in Punjab have been working in a dual mode to overcome the pandemic restrictions. Those who have mobiles/smartphones are taking online classes, which goes on for around an hour or two. Those without smartphones come to school themselves or their parents drop notebooks on which teachers give them work assignments. Kaur, a primary section teacher at the Badial Government Elementary School, uses a video editing app to prepare her lessons and share them with her students.

What is even noteworthy is the fact that government schools in the state have been witnessing largescale migration from private schools. In the first week of April, Punjab saw the transfer of over 33,000 students from private to government schools. As per Punjab government data, an estimated 3.5 lakh students have shifted from private to government-run school during the pandemic period, the main reason being economic challenges for parents.

Education in rural areas has always been the weak link in India. According to experts, 12 years of school in rural India means effective learning of just 6.2 years. And with the virus lurking, it will likely further drop to 5.5 years.

But even if schools and colleges reopen—not in the near future though—it’s unlikely to be the same old story. Manit Jain, co-founder of Heritage Xperiential Learning School in Gurgaon, says it will be difficult for children whenever they return to formal school. “We have designed our curriculum and practices to help ease our children back to the physical school. There will be a lot of emphasis given to the social-emotional needs of our children and the school has a social emotional learning team, as well as a counselling team that will be working closely with all our students.

Being away from school for such a long time could be tough for primary and early school students, says Anil Kumar, principal of Kendriya Vidyalaya, IIT Ropar. “The potential two-year or longer miss can be overcome in some cases but not in all the cases…The loss could be emotional, social, learning, cognitive and exploration. It would be felt and start resonating once the kids come back to school. It will have ripple effects when the examination system is resumed and kids can become more vulnerable which needs to be tread upon carefully,” he says.

Then there is the matter of parents facing financial hardships due to the Covid-induced economic downturn, which is leading to delay in payment of fees and, in worst case scenarios, children being pulled out of schools. Schools, too, are going through a financial crunch and are having difficulty meeting the operational costs, and are being forced to adapt different payment structures and fee cuts to avoid dropouts.

Smaller schools are now reinventing their business models to ensure they don’t close down. A principal of a Delhi private school says on condition of anonymity, “From the current session we have adopted new model for our teachers. They are divided into three categories—ad-hoc teachers who will be paid regular salaries for the complete academic year, visiting teachers who will be paid on per hour basis and thirdly, teachers who will just give us video tutorials. The fees had to be reduced because kids were dropping out, we had to opt for this model to ensure that no teacher is laid off.”

Parents, even those who can afford the money, are growing increasingly uncomfortable with payments for their children. Noida-based Nitin Sharma feels that his daughters’ school is “charging heavy tuition fees with only an hour of online class”. He has two daughters, aged ten and six. “We paid over eleven thousand rupees as fees per month for each kid at Noida’s international school last year. Just one or two classes were conducted per day of 45 mins each. Forget about extracurricular classes, even their syllabus hasn’t been completed.”

The emotional scars of the pandemic are beginning to show, even in adults. For children, they are even worse, say experts. Anger issues have emerged. So have withdrawal symptoms. Mumbai-based psychotherapist and child counsellor Padma Rewari—a mother of two teenage kids—says she has noticed mood swings even in her own children. “I sometimes see my son avoiding his friend’s phone calls which was never the case before. But I know that he is more of a child who likes to meet and converse.”

“School, which was the ground for interactions, debates and participations, has suddenly come to a halt. This is surely playing on the minds of children and young adults, who are frustrated and have developed anger issues. I know of younger kids who are not able to focus and have become extremely restless being indoors with no social play. This has led to attention-seeking behavioural issues among children,” she adds.

Some schools are starting campus classes but only after putting students through the Covid-cleanser. In Shimla, one of the oldest residential schools—Bishop Cotton School—has started an innovative experiment in itself. At the start of term, all boys returning to BCS had to have a negative RT-PCR test prior to 72 hours before returning to the campus. The boys are then assessed by medical teams before being re-admitted.

Different classes arrived back on different specified dates in a graded fashion. Pupil drop-off was strictly supervised and parents were not able to enter the campus. The classes remain segregated in separate ‘bubbles’. Each bubble has its own accommodation with separate entrances. Bubbles eat, sleep and play together. During the school day, pupil adopt all anti-Covid measures which include wearing of masks, regular sanitizing and social distancing. BCS director Simon Weale says the school is able to offer relatively normal timetable, including exercising every day, playing inter-house sports matches within their bubbles. “A number of students quickly changed shape, having lost the weight they had put on in lockdown,” he added.

Higher Education

Currently hardly 26 per cent of the students who complete their school education in the country enrol for higher education. Though the percentage is not impressive, the rush for getting admission to prestigious colleges is very tough, with some colleges conducting their own examinations apart from the government-held exams to admit the best candidates. Already, some of the colleges have opened their portals for the admission process though the final school leaving exams and those for specialized courses like engineering and medicine are still to be conducted. Unlike the norm, like last year, this year too admissions are unlikely to be completed in time to enable institutions to begin their new semester in July. The last semester in most schools and colleges has been a “rushed semester”, with the summer break in schools and colleges falling a casualty as online classes are continuing.

Prof. D P Singh, Chairman, University Grants Commission (UGC), the apex regulator of higher education says, “Webinars, virtual classrooms, teleconferencing, and conduct of examinations in offline/online (pen & paper)/blended (online+offline) mode became a part of our academic lexicon. We saw online viva-voce examinations for Ph.D/M.Phil students, and online University convocations taking place,” Singh says.

Today, the academic community is using an entire range of online platforms to secure the delivery of education and instruction in keeping with individual and national objectives. This massive shift in our pedagogical approach has resulted in exponential growth in the online education sector in the country, a phenomenon that is expected to continue to provide a fillip to the education sector for decades to come, observes the UGC chief.

During the first wave of Covid, almost all the institutions had closed their campuses but post the lockdown, there was some relaxation with some of the institutions holding classes and allowing students to avail laboratory facilities in batches. But the rise in Covid cases since March has led to most institutions going back to online classes, though in some cases the students are continuing to stay in hostels but attending online classes.

Prof. Manikrao Salunkhe, vice chancellor of Bharati Vidyapeeth, a deemed to be university, also shares similar concerns. The fact is that for teachers too there is more ease in conducting physical classes as even though most students log in, there is no surety how many continue to be attentive during an online class as there are constraints of attending a lecture/demonstration on the small mobile screen which many students use. The interaction in most classes seems to be limited to around 20 percent while the others seem not too comfortable. There are also problems in the case of some streams of education like science and technology, engineering, etc., where laboratory work is crucial. This missing element in technical education could prove to be a major lacunae when the students who have passed out last year or are in line to do so this year will face many challenges in the job market. While it may not become a lifelong handicap, many of the students eager to be employed will need additional training in the short term, particularly where certification is deemed vital. Many of the students passing out of tech colleges have already started taking add-on courses.

The pandemic has thrown up many questions and also left many lessons for the world. How much we have learnt will determine how the country’s education scenario unfolds.

—Inputs from Lachmi Deb Roy and Ashwani Sharma

.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=768&dpr=1.0)