India’s air quality has been ranked as the most polluted in the world. In 2019, India had 10 out of 15 most polluted cities on earth, according to a recent report by IQAir, a Swiss air quality technology company. And there are several scientific reports that show that increase in air pollution levels is taking a toll on public health as well as the economy. For example, a 2016 World Bank study estimated that India lost more than 8 per cent of its GDP in 2013 because of air pollution as welfare losses and forgone labour output. Another study by IIT Bombay highlighted that air pollution cost $10.66 billion to Delhi and Mumbai alone in 2015 or about 0.71 per cent of the country’s GDP. Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago also estimated that on an average, life expectancy of Indians is reduced by 5.2 years due to air pollution.

Back in 2015, increasing air pollution levels had compelled the ministry of environment, forest and climate change (MoEF&CC) to come out with new emission standards for coal-based power plants in which, for the first time, the government stipulated limits for sulphur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxide (NOx) and mercury (Hg) emissions as well as water consumption limits. A study done by IIT Kanpur in 2015 substantiates the fact while highlighting that 90 per cent reduction in SO2 from power plants within 300km of the national capital Delhi will result in the reduction of approximately 35 micrograms per cubic metre of PM2.5. Particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) in air does serious damage to our respiratory system and creates multiple medical complications. High levels of SO2 is also linked to cardiovascular diseases.

Installing Flue-Gas Desulfurisation (FGD)

According to the December 2015 notification, all coal-fired power plants across the country had to install SO2 control technology within two years, but almost none of them complied to the timeline and showed very little or no progress toward compliance. Instead of imposing penalty for inaction, the government approached the Supreme Court to seek extension in the timeline, which shows a lack of political and institutional willingness to curb pollution arising out of coal-fired power stations.

The power plants were granted a staggered timeline running till 2022, according to a phasing plan prepared by the Central Electric Authority of India (CEA) in consultation with power generators and was approved by the Supreme Court.

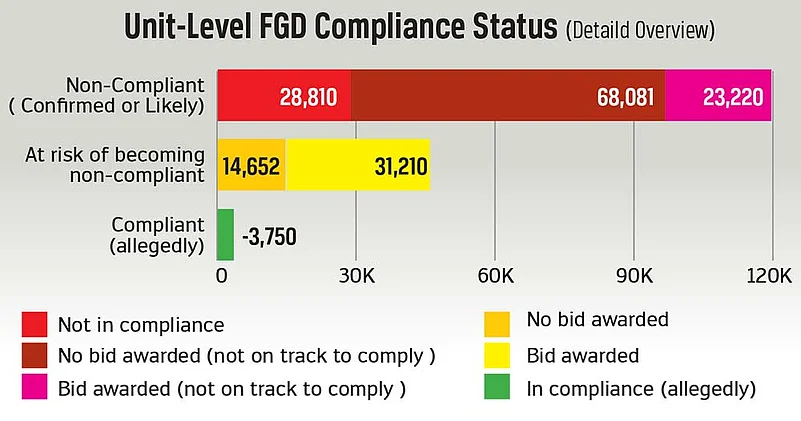

According to CEA, as of October 2020, out of the power plants with nearly 170 Gigawatt (GW) total capacity, more than 28 GW power plants which had phasing timeline before October 2020 are operating illegally or are in non-compliance of the 2015 notification; 3.7 GW capacity are complying, nearly 46 GW is at the risk of becoming non-compliant; and, 91 GW capacity is nearly confirmed or likely to be non-compliant, looking at their progress and phasing timeline for the respective units.

Although there have been some attempts by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) to impose marginal fines, but no strict action has been taken for non-compliance, even the fines haven’t been paid by most of the generators and they continue to operate. This October, the MoEF&CC amended the notification further, diluting the NOx norm for coal-based power plants installed between 2003 to 2016 from 300 mg/Nm3 to 450 mg/Nm3.

The burning of dirty coal has remained hidden over stubble burning or vehicular emission issues. Even bursting of firecrackers on Diwali have had more media coverage. Coal-based power plants are the biggest sources of air pollution. And they are relatively the easiest to control at source. However, the majority of power generators have used one reason or the other as a tactic to not install SO2 emission control devices.

Now, five years after the notification came into existence, the CEA and CPCB have joined hands to lobby against the installation of FGD in power plants. The arguments and recommendations question the formulation of the MoEF&CC notification and completely ignore the effects of SO2 emissions and it impacts on millions of people across the country. By asking for repeated extensions, the strategy for the power sector is now to take the emission control status to pre-2015 levels—when there was no regulations. This is something the sector has been advocating for the past five years, questioning all scienctific studies on air pollution and the harmful affects of SO2.

The story of emission standard notification and its struggle to reach any degree of compliance is a lack of political and institutional will. If we are to make a better India and a healthy future, all this needs to change at a fundamental level. We need a greater focus on the implementation of rules and regulations, with a stricter and more committed political and institutional will to help clean the air we breathe.

(Views are personal)

Analyst with the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA). He is an expert on implementation of emission standards for coal-based power plants in India.