The moves have been fast, very fast. The Trinamool Congress (TMC) unleashed the most aggressive resistance to the NDA government this monsoon session of Parliament—disrupting sittings nth number of times together with the other Opposition parties. A Rajya Sabha MP of the party was suspended in the fourth week of July and another six attracted the same punishment in August for “disorderly conduct”. The party’s aggression has been equally intense outside Parliament: from staging protests to coordinating with parties unaligned with the BJP. This offensive attracted eyeballs, media space, and new associates such as Right to Information (RTI) activist Saket Gokhale who confessed that the TMC’s aggression made him join the party in New Delhi. This charm offensive is playing out miles away from the national capital too—the TMC is courting smaller but influential regional players in Tripura and Assam to expand its footprint in the Northeast following its victory in this summer’s assembly elections in West Bengal. The bait has been dropped, but recent events don’t suggest it can reel in much of the catch. So it seems now.

Take the TMC’s moves in Assam, for instance. The party reached out to two leaders—activist-politician Akhil Gogoi, an MLA of the Raijor Dal that he founded before the Assam assembly elections, and Naba Kumar Sarania, Assam’s sole Independent Lok Sabha MP. Gogoi is a multi-role leader: RTI activist, farmer’s leader, anti-Citizenship Amendment Act campaigner, and one of the leading voices against the BJP. He was arrested and put in jail after anti-CAA violence swept the state in the winter of 2019-2020. He contested the polls from prison, won, and was freed on July 1 this year. The TMC wasted no time to contact him within weeks of his release. He ticks all the boxes to be an ally, or more than that. He was offered a simple proposition: merge his party with the TMC become its Assam unit chief. Gogoi disagreed. But he kept the door open for an alliance and to work together. This August, he praised the TMC chairperson and West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee, publicly announcing that he would like to see her as the next prime minister.

For parliamentarian Sarania, the TMC offered a similar deal. The office of Abhishek Banerjee, Mamata’s nephew and the TMC’s all-India general secretary, got in touch with him. But Sarania—a former commander of the militant Ulfa and the son of an army man—refused, but didn’t rule out an alliance with the TMC. Parleys with these two leaders may not have blitzed through like the way the TMC would have expected, but the party’s poke-and-prod efforts to win politicians to its ranks have not been unsuccessful either. The biggest catch so far is Sushmita Dev, the Congress’s women’s wing chief and a former Lok Sabha MP from Assam. She is the daughter of Santosh Mohan Dev, the late Congress heavyweight whose name still commands unfettered loyalty among a large section of the electorate in southern Assam’s Bengali-majority Barak Valley. Sushmita joined the TMC on August 16, and the party couldn’t be happier as it needed a prominent face in Assam. Her entry into the TMC has kindled hopes of talks with Gogoi and Sarania yielding positive results.

For her part, Dev might not restrict her activities to Assam. She could play a role in neighbouring Tripura too, where her father had a significant influence. Tripura has been on the TMC’s spotlight as part of its expansion drive since the assembly elections in Bengal. Unlike in Assam, the TMC has made significant inroads in Tripura, becoming the main opposition party in 2016 during the last leg of the Left Front rule. But it lost ground in the subsequent years after the TMC’s entire legislative team of six MLAs moved en masse to the BJP in 2017. The TMC is now rebuilding its unit in Tripura, hoping to strengthen the ranks with people from other parties, especially the Congress, or whatever is left of the party.

The moves in Tripura have been rapid, so much so that these led to altercations with the state’s BJP government. A case in point is the detention of 23 employees of poll strategist Prashant Kishor’s Indian Political Action Committee (I-PAC) when they went there to survey the political situation. Kishor is a TMC adviser and played a significant role in the party’s victory in Bengal. The TMC rushed senior leaders Derek O’Brien and Kakoli Ghosh Dastidar to Tripura after the police action on Kishor’s staffers. “Rarely leave Delhi when #Parliament is in session. But flying to Agartala early Thursday morning,” O’Brien tweeted on July 28, reprising the party’s seriousness over this small, hilly state. The I-PAC team members obtained anticipatory bail and on the following day, seven Congress leaders, including former minister Prakash Chandra Das and former MLA Subal Bhowmik, joined the TMC. Bhowmik had been a Congress MLA and Tripura BJP vice president before returning to the Congress in 2019.

Abhishek Banerjee reached Agartala on August 2 to formally announce that they had made Tripura the bull’s eye for the assembly elections due in early 2023. “We will visit thrice a month,” he declared. Soon enough, a delegation of youth leaders from Bengal came under attack in the state on August 7, following which they were taken to Khowai police station. Party supporters staged an overnight demonstration outside the police station, only to be arrested along with three TMC leaders the next morning for violating pandemic restrictions. Before afternoon, a TMC team led by Bengal law minister Malay Ghatak and education minister Bratya Basu reached Tripura, ensured their bail, and remained in the state for the next two days. Abhishek Banerjee too flew to the state. Since then, TMC MPs, Bengal ministers and state unit leaders has been flying in and out of Tripura, organising events, planning protests and, above all, to keep the party in the news and in the public gaze.

The TMC is spinning the repeated attacks on its supporters and leaders to its advantage, firing away a volley of accusations against the BJP. It has even alleged that the ruling party has asked hotels in Agartala not to book TMC leaders from Bengal. As a counter, the BJP’s youth and women’s wings organised a statewide demonstration on August 13 against the TMC’s “slandering campaign and conspiracy” against chief minister Biplab Deb’s government.

The TMC has also reached out to Pradyot Kishore Manikya, the royal scion of Tripura, who leads the Tiprasa Indigenous Progressive Regional Alliance (TIPRA). Manikya has not ruled out an alliance, at least for now. He has praised Mamata Banerjee and condemned an attack on Abhishek Banerjee’s convoy. Besides, the party is keeping a close tab on the BJP’s internal troubles, especially with a number of leaders dissenting against chief minister Deb. One of the disgruntled BJP leaders is Sudip Roy Barman, who went from the Congress to the TMC in 2016 and to the BJP in 2017. He is now a minister in Deb’s government. Whether Roy Barman’s recent public statements against his government are indications of any growing proximity with the TMC or a bargaining tactic for greater say within the BJP remains to be seen, but the TMC’s sudden foray into the state has prompted the national leaderships of the BJP and the Congress to accord special attention on Tripura.

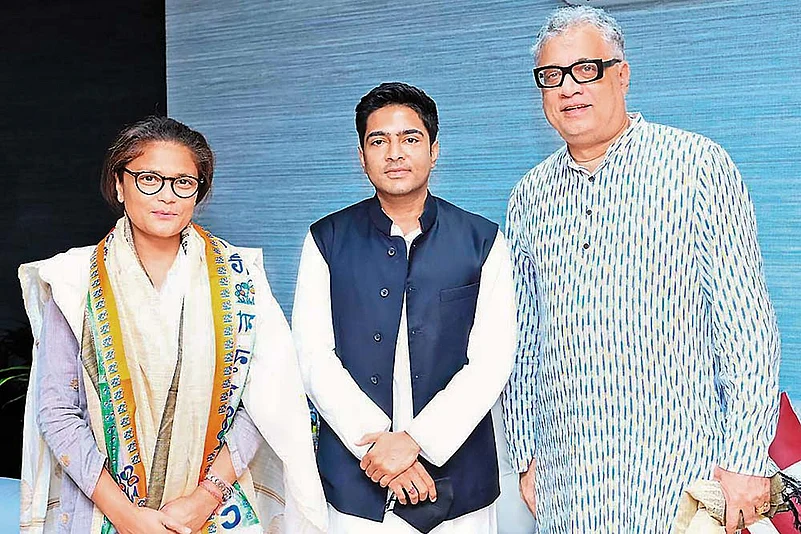

Sushmita Dev with TMC leaders Abhishek Banerjee and Derek O’Brien

However, the TMC is accused of playing a double game. It is coordinating with the Congress at the national level and targeting the party in Tripura and Assam. Sushmita Dev sees no wrong as such poaching hews to every party’s policy. The Congress too takes leaders from other parties, she said. Besides, as political observers point out, the TMC was born out of the Congress in 1998 and had already “finished” much of its parent party by consistently weaning away leaders and supporters since coming to power in Bengal in 2011. That hasn’t stopped the two parties from launching a coordinated attack against the BJP at the national level, they argue.

The other contradiction is of a greater magnitude: the TMC’s main political pitch of representing Bengali ethnic pride may work to an extent in Tripura, but would hardly help the party in Assam. Gogoi has cited that he and Mamata Banerjee are against the CAA, although it is left unsaid that the context for their opposition to the citizenship law is completely different. The TMC is against the law because the party considers it discriminatory against Muslims. Gogoi’s party opposes it because they think it could undo the gains of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam by allowing Bengali-speaking Hindu Bangladeshi immigrants to become Indian nationals. And it is the NRC that could prove to be the unbridgeable gap between TMC’s possible local allies in Assam. The TMC is opposed to the idea of a pan-India NRC, and also a critic of the exercise in Assam, saying that it was mostly the Bengalis who had been victimised. The party’s possible Assam allies have been vocal supporters of the NRC in the state.

Cutting the volume on the NRC in Assam could be politically suicidal for Gogoi and Sarania, political observers say. “I really do not understand how the TMC can strike an alliance with Gogoi, who had spoken vehemently for Assamese domination at a rally in the Barak Valley three years ago,” says Tapodhir Bhattacharjee, a literary theorist and former vice chancellor of Assam University who lives in Silchar town, Barak Valley. Since Independence, every political party in Assam has utilised the ethnic conflict to their advantage and “a sense of fear of an imaginary Bengali domination” runs deep into Assamese society, he observes. “From that perspective, I don’t see any prospect of the TMC except in the Barak Valley and a couple of other districts with a significant Bengali-speaking population.”

In Tripura, though an alliance with TIPRA can significantly boost the TMC’s prospects, Manikya’s demand of a written assurance to guarantee the local tribal population’s constitutional rights—something that he has described as “more than mere autonomy”—might be difficult for Mamata’s party to promise. “National parties coming to Tripura should not expect to strike an alliance easily, just because they have more money. We, the indigenous people, may have less money but we value self-respect. Without a written commitment for Greater Tipraland, which includes implementation of the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution, there will be no alliance,” Manikya says. He explains that Greater Tipraland will include the well-being of every indigenous people living in or outside the Tripura Tribal Areas Autonomous District Council (TTAADC).

Much like its slogan, the TMC knows it has to play its game: “Khela Hobe!” The question is will it succeed in asserting its position in a state that has voted the BJP overwhelmingly in the previous elections to end 25 years of Left rule? It’s a match held on an uneven pitch, and nobody can tell better than a certain Manik Sarkar how the ball swings. The Left, formally the main opposition party in the state, is watching from the sidelines. Former chief minister and CPI(M) politburo member Manik Sarkar knows a trick or two.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Khela Hobe On A Sticky Wicket")

By Snigdhendu Bhattacharya in Calcutta