“What does Oscar Wilde want to convey in this line, Sir?” pops a question from one of the 127 windows on the computer screen of Obaidur Rahman Nadwi (44), English teacher at Dar-ul Uloom Nadwatul Ulama, Lucknow, one of the most recognised madrasas in the country.

Nadwi, in white kurta and topi, with the English textbook in his left hand, explains with expressive actions of his right hand, as if he is teaching in a classroom. Today’s module is on Oscar Wilde’s short story The Selfish Giant.

The question comes from Mohammad Faheem (24), who hasn’t switched on his video. Sitting in Hardoi, about 100 km from the madrasa, he, like 126 other students, is attending his Alia Rabia (BA final year) classes. By the time Nadwi gives his answer, other students have started chattering. Nadwi scolds them: “One at a time, please.” And the class goes on.

Madrasa education, particularly in the Hindi ‘heartland’, has been in the Hindutva crosshairs for ages. A stereotypical image of kurta-and-topi-clad kids getting indoctrinated at these Islamic schools has got etched in the minds of India’s Hindu majority. Even some Muslim academicians and influencers feel the system needs reform. Interestingly, some of the churn they want to see is already happening at madrasas and state madrasa boards across the country. Nadwatul Ulama is among those at the forefront of this desire for reform.

At the Lucknow madrasa, since physical classes—suspended since March 2020 in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic—haven’t started yet, all classes are being held online. In this virtual classroom, wearing school dress—kurta, pyjama and topi—is not binding, so some students are attending in casuals, others in uniform, while many more don’t have their cameras on. The set-up is no different from an online class of any reputed private school in the country.

But, out of thousands of madrasas, few can afford to run online classes during the pandemic, as many students can’t afford laptops or smartphones. “Here, many students connect via cell phones. We have pretty good attendance,” Nadwi says, adding that about 4,000 students between Class XI and MA have been taking online classes on different subjects every day.

Run by Nadwatul Ulama Association, the 60-acre campus houses classrooms, hostels, library, quarters for instructors, sports ground and everything else any university can boast of. The association has 200 branches across the country that impart primary and secondary education.

“Online classes are going on in all these places as well,” Nadwi says. “The schools teach all subjects like mathematics, science, social science etc, according to the curriculum of respective state boards. Students who pass out from these schools can take admission in our university or elsewhere.”

Besides madrasas like Nadwatul Ulama, which have classes from primary to post-graduate, there are others offering classes up to Class XII. One such well-known madrasa is Madrasatul Islah in Saraimeer, Azamgarh, UP. Spread over 52 acres, it imparts classes in computer science and skill development, along with the Quran.

“For primary section, we have our own books. For the rest, we use NCERT books. We teach English, science and maths like other government or private schools,” says an instructor. “We also have skill development courses in which students are taught how to repair fridge, AC, TV and other electronic goods.”

Then there are smaller madrasas that teach students up to primary or secondary classes. Besides these broad types, there are many other categories of Islamic schools. Madrasas are ideologically divided into four types—Deobandi, Barelvi and Ahl-e Hadith (Sunni), and Shia. Another way to categorise them is on the basis of their affiliation—private-run or affiliated with the state madrasa board. “Some states like West Bengal, Bihar, Odisha and UP have madrasa boards,” says Tauqeer Rahi, who has done a PhD on madrasa education in India. “Since they follow the syllabi of state boards, passouts can get admission in other schools as well.”

Muslim scholars say there are about 50 madrasas in UP that are considered pioneers in education reforms. But, in the absence of a central regulatory body, their number is unknown. Also, they have no common syllabus, and although modern education has been introduced, their focus remains on producing Islamic scholars.

Justice M.S.A. Siddiqui, who served as the chairman of the National Commission for Minority Education Institutions for 10 years from 2004 to 2014, says he had encouraged madrasas to adopt modern education. “I’d proposed the establishment of a Central Madrasa Board for a common syllabus and curriculum, but heads of big madrasas opposed it, and it never took off,” he says.

He adds that due to the absence of any standardised curriculum in all madrasas, it is difficult to bring parity with other recognised school boards. “Many students who pass out of madrasas face difficulties in getting admission in government-recognised higher education institutes,” he says.

Some universities like Aligarh Muslim University, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Jamia Millia Islamia and Jamia Hamdard have recognised some of the top madrasas, and admit their students for Arabic and Urdu courses.

“If a candidate completes BA (Arabic) from Nadwatul Ulama, he will get admission in BA (Arabic) in other universities, as they treat our BA as equivalent to Class XII,” Rahi says.

There are other structural issues. Madrasas don’t offer co-education, and the ones for girls are few and far between. Jamea-tus-Salehat in Rampur, UP, is one which imparts modern education to girls up to Alima (final year).

The seven-member Sachar Committee, headed by former Chief Justice of Delhi High Court Rajinder Sachar, had found only 4 per cent Muslim students go to madrasas.

Students at a computer class, Supaul, Bihar

“Due to low levels of education, a poor Muslim family has many kids, making it financially unfeasible for them to send the kids to good schools. Madrasas cater to such families, as they offer free food and residential facilities to kids,” says Jasim Mohammad, former media advisor of AMU. “Those who go to madrasas mainly end up as religious teachers.”

Under its madrasa modernisation scheme, the central government gives grants to teach maths, science and computers, build laboratories for senior classes, etc. However, only some madrasas accept these grants; the bigger ones stay away, as they fear it to be a government ploy to interfere in their academic matters.

Justice Siddiqui adds that grants often lead to fraud and corruption. “Over 90 per cent of madrasas don’t take grants, and run on donations. Those who do, often indulge in fraud, and ruin the reputation of the system,” he says.

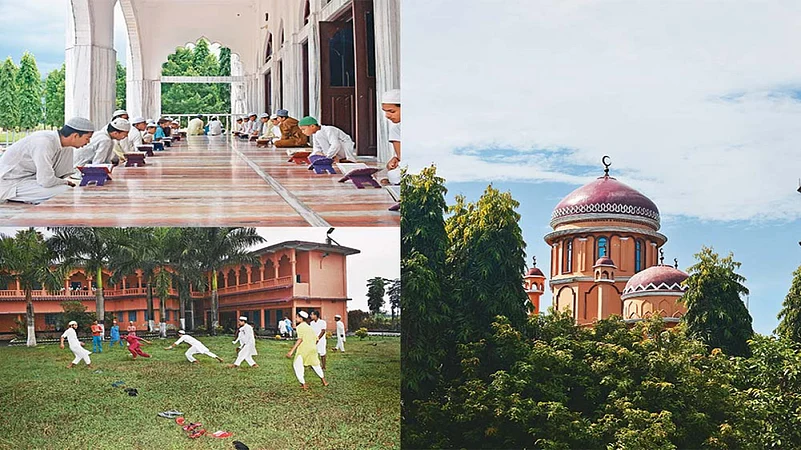

From the quiet, tree-lined three-acre compound of the madrasa it is hard to imagine there are hundreds of students studying here. There is a majestic mosque to its right, with a squeaky clean marble floor. The Jamia-Tul-Qasim Dar-ul Uloom-Il-Islamia madrasa in Madhubani village of Supaul district, about 300 km from Patna, breaks the stereotype in many ways. It instructs in three languages—Urdu, English and Hindi—and teaches computers, history, mathematics, geography and science.

Md. Shahjahan Shad, general secretary, Seemanchal Development Board, who is associated with the madrasa, says, “Our aim is to provide students with both deeni (religious) and dunavi (worldly) education, so our kids don’t feel alienated when they enter the mainstream.”

The founder, Mufti Mahfoozur Rahman Usmani or Mufti Sahab, passed away recently after a heart attack. He started the madrasa in a hut with only three teachers and 13 children. Slowly, it started gaining popularity among locals. “Usmani Sahab had studied abroad. When he returned, his father asked him to do something for the village. So, he opened a madrassa in this backward area, which would function like mainstream schools,” says Shad.

It has 1,000 children on its rolls. There is also a hostel accommodating 600 students from surrounding areas. Since last year, Covid-19 restrictions have curbed activities. “But now, schools are opening, and we’ve started classes with social distancing,” says Mufti Mohammad Ansar Ahmed Qasmi, the principal. “At present, we have about 250 students, with around 200 boarders.” The madrasa has a staff of 70 who teach the syllabi of both the Bihar and madrasa boards, and admits kids till Class VII.

What makes it stand out is that it has made sports compulsory. Every evening, all the children are encouraged to participate in sports. They play football, cricket, volleyball and kabaddi. Qasmi says, “Locals who are good at these sports sometime come over to teachthem. Also, before start of morning classes, we make all students run around campus.”

Class routines vary according to the season. At present, classes are divided in two spans. The first starts at 6.30 am and ends at 11 am. Thereafter, the kids have lunch and take rest. The second round starts at 2.30 pm, and lasts till 5 pm, after which, they get an hour and a half to play.

We reached the madrasa in the afternoon. Children were trooping out of hostel rooms towards the kitchen for lunch. At several places—some in classrooms, others in the masjid portico—classes had begun with smalls batches of students.

“We want to open a medical college here. Land has been acquired, but due to the lockdown, work is stalled. We’re also planning a girl’s hostel, after which we can start offering classes to girls. Some Hindu children also attend classes here, often to study Urdu,” says Qasmi.

The madrasa runs completely on donations. The admission fee is Rs 400-500, but economically weaker children are taught free of cost. Admission is easy—all parents need to do is produce identity cards of their wards. The parents also need to sit for a simple test. The quality of education, ambience and focus on sports are all big draws among children who enroll here. Kahaf Zaheer (14), who comes from a well-to-do family and voluntarily pays monthly fees, says, “I was earlier staying at hostel in Patna, but the quality of instruction was poor there. Hygiene on campus was terrible. So I left and got admitted here two years ago.”

(This appeared in the print edition as "New Moon Sighted")

By Jeevan Prakash Sharma in UP and Umesh Kumar Ray in Bihar