In October 1988, an 18-year-old boy watched intently as his father organised a sit-in protest with close to five lakh farmers in the heart of Delhi. The stretch between Vijay Chowk and India Gate was full of farmers—and their tractors, buffaloes, carts, ploughs, and cattle were all parked on the adjacent lawns. A mini village had suddenly taken shape at Boat Club, so called as visitors could row flat-bottomed boats in the shallow tanks on both sides of the road.

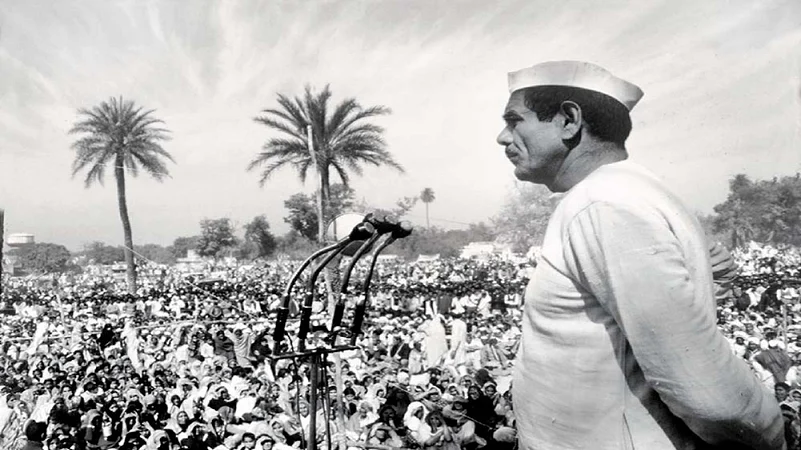

The demonstration was organised by Bharatiya Kisan Union (BKU) chief ‘Baba’ Mahendra Singh Tikait, who would sit with his trademark hookah, supervising the protest demanding higher remunerative prices for sugarcane produce, waiver of water and electricity dues and concessions in their tariff. This was an extension of an earlier dharna at the office of the divisional commissioner in Meerut, Uttar Pradesh. When the authorities failed to convince the farmers, then UP chief minister Vir Bahadur Singh invited Tikait to Lucknow for negotiations.

ALSO READ: Running On Jat Fuel

But Delhi was closer, and its corridors yielded more power. So Tikait led his followers right into the national capital and continued the protest for a week. The Congress-led government in Uttar Pradesh later conceded to a major part of his charter of demands. Now, three decades later, the son has led his followers to Delhi in yet another farmers’ stir, this time against three contentious farm laws.

“I was part of the agitation at Boat Club,” says the son, Rakesh Tikait, national spokesperson for the BKU. “That rally was confined to only one spot but today it is wider, taking place at several sites around Delhi. That time, farmers’ representation was more from Uttar Pradesh and Haryana…Today Punjab has bigger participation. It is significant, and I’m proud that Sikh participants are fighting for farmers’ cause.”

ALSO READ: ‘They Called Us Khalistani, Pakistani’

Tikait, now 51, has become the face of farmers’ resistance when he defied the administration’s directive to vacate the Ghazipur protest site at Delhi-Uttar Pradesh border on January 28. Leaders of the umbrella organisation, Sanyukt Kisan Morcha, hailed his efforts the next day in a meeting.

Though his brother Naresh—currently the president of BKU and the Chaudhury of the khap—has inherited his father’s legacy, it is Rakesh who has emerged as the popular farmer leader. There are reports that the brothers have differed on several occasions. Even on January 28, Naresh announced that the protest at Ghazipur will end as there was pressure from the administration to vacate the spot. Rakesh refused to move and said that the protests will continue. This again fanned another round of speculation that a fallout was imminent.

In Ghazipur, meanwhile, Rakesh vowed to continue the struggle and broke into tears, complaining of a slander campaign targeting especially farmers from Punjab. Soon after the teary face was beamed live on television and went viral on social media. Hundreds of farmers who had returned home after the January 26 tractor parade, turned their vehicles towards Delhi once again.

Tweeted Naresh Tikait in Hindi that night, “The tears of Choudhary Mahendra Singh's son and my younger brother Rakesh Tikait will not go in vain. There will be a mahapanchayat and we will take the movement to a decisive stage.”

A massive crowd gathered at the mahapanchayat on January 29. According to reports, there were over 10,000 participants, perhaps the biggest congregation in recent times at the GIC ground in Muzaffarnagar. Among those present were several local political and religious heavyweights. The meeting pledged support to the ongoing agitation and wanted to immediately march to the protest site. Political observers felt that the state government and the Ghaziabad administration had mishandled the situation, and this could now strengthen the protests. The decision of the authorities had hurt sentiments of farmers, especially from the Jat community, which carries significant political clout in western Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, and parts of Rajasthan. The developments also seemed to have brought the brothers closer.

ALSO READ: Sow No Hope

Rakesh Tikait ruled out any friction, saying that the brothers follow a very clearly demarcated role in the organisation. “While he primarily takes care of the khap, he is now at our village addressing matters pertaining to the area and its residents. I am sitting here at the Ghazipur protest site,” he says (see interview).

Naresh Tikait too ruled out any differences, claiming that the entire clan is sticking together in this movement. Reiterating his brother’s statement, he said that they are staunchly against violence or politicising the protests. “We need to respect each other. The dignity of both (government and farmers) need to be maintained. No way shall we ever allow the Prime Minister’s dignity to be compromised. We are confident of reaching a solution peacefully.”

The Tikaits are from Sisauli of Muzaffarnagar district in Uttar Pradesh. Mahendra Singh Tikait was born in 1935 in this village. He inherited the title of Chaudhary (head) of the Khap Baliyan when he was only eight-year-old, after his father Chauhal Singh’s demise. It is said the khap had passed a resolution in 1941 saying that the Chaudhary of a khap has the right even to demand the lives of its members. This Chaudharyship of a khap panchayat is a hereditary title. Such a leader enjoys administrative and adjudicative powers over the khap. This legacy passed on to Naresh Tikait after the death of Mahendra Singh Tikait in 2011.

Despite the power and local mass base they enjoy, political gains eluded the Tikaits. Mahendra Singh Tikait could not even become a member of the legislative assembly as the sway of Chaudhary Charan Singh over the Jats and some other agricultural classes in Western Uttar Pradesh could not be dented.

Rakesh Tikait had also contested the 2014 general elections from Amroha, a predominantly Jat constituency. But he fared poorly, ending at the fourth spot and securing just a little over 9,500 votes. Having noticed his rise in the ranks, and taken by the popularity among farmers that time, the leader of the Rashtriya Lok Dal, Ajit Singh, had nominated him as their Lok Sabha candidate. However, he failed to win over the electorate.

In parliamentary election five years later, Rakesh claims that he had voted in favour of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). “Today it is ironic that I’m protesting against the policies of the same party that I voted for,” he said. He stressed that for him, farmers’ rights are a priority and that “politics and political inclinations are different from seeking our rightful share”. However, he denied nurturing political ambitions and claimed that his agitation will always remain non-political.

He asserted that no political leader is ever allowed to share the stage and neither to share their views over the public address system. “We have made separate arrangements for them. But we can’t stop them from coming; any visitor here is akin to a guest at our home,” he said.

Leading protest rallies is nothing new for the BKU spokesperson who claims that any child born in the Tikait household will have to take an active part in a struggle someday. “The Tikait legacy was there and it still continues,” he stated. His activism has led to his arrest several times. Not only Uttar Pradesh, but he has led farmers in a protest against land acquisition in Madhya Pradesh. He had earlier led a rally in Delhi demanding higher price for sugarcane. He served jail terms in both cases.

Not all farmer unions, however, hail him as a leader. Some leaders, like V.M. Singh, have withdrawn support from the ongoing protests. Singh had blamed the leadership for “misleading protesters” and going back on the agreement with the Delhi Police regarding the route to be followed for the January 26 rally. Similar allegations were made by the Bharatiya Kisan Union (Bhanu) president, Thakur Bhanu Pratap Singh, when pulling out of the protest on January 27.

Whatever brickbats he may be receiving, Rakesh Tikait is now a beacon of hope for the millions of farmers. Leaders of Opposition parties are making a beeline to the site in Delhi’s border which is now his temporary address. Looking back, he should not be regretting the decision of having quit a policeman’s job to police the rights of the tillers.