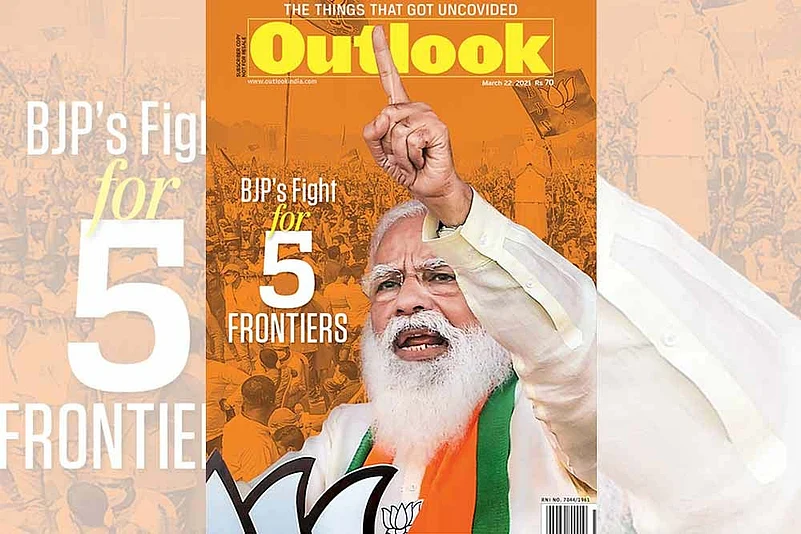

Assembly elections are cussedly regional affairs —they are about local satraps, debates heavily accented in the local language, and last-mile politics. Why then would a bunch of five assembly polls, strewn across India’s corners, elicit talk of a ‘national’ factor? Especially when they present such a mismatched bouquet? Indeed, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Pondicherry have robust differences between themselves in terms of political culture and history; adding Bengal and Assam to the mix can scarcely add any coherence to the picture. Why, then? Well, because there’s one element common to all of them: the BJP as a real, live factor. And the coincidental fact of these five states being geographically so far-flung actually enables us to discern a deeper movement in Indian politics. The BJP’s own growth as a truly national presence—a feat not yet accomplished, but an ongoing process that we can map in a month from now. Almost like a ‘download in progress’ bar.

But what is the BJP if not a national party? Well, from the days of its parent party, the Jana Sangh, India’s foremost right-wing formation has cultivated a self-image of being truly pan-Indian in its footprint—the first two words in that appellation, ‘Akhil Bharatiya’, signified precisely that scale of ambition. Yet, for decades, even after the BJP was formed in the 1980s, it carried a distinct shade of something quite opposite and operated from a narrow horizon in several ways. Its social base was urban and very ‘northern’, its core drawn from the elite castes. That started changing with the Ayodhya movement, which also featured a young Narendra Modi as one of the then-unknown charioteers. Much water has flown down the Sabarmati since then. Modi’s very persona—grand and gladiatorial in mien, and seemingly teflon-armoured—gives the BJP an icon that can travel, a batsman whose style can potentially master all pitches.

ALSO READ: Like Gold In A Furnace

Still, there remain vast gaps on the map. While the BJP, first during the Vajpayee-Advani era and now under Modi, has long outgrown its old straitjackets, its absence is fairly conspicuous in large swathes of the east and the south. Take the east. Assam was taken only in 2016, quite a frontier breached. But even Bihar, which could conceivably be seen as part of an eastern bloc, truly fell into its lap only last November. Bengal, made of the same Gangetic alluvium, seemed to beckon. That’s why, the day after the BJP powered the NDA to victory in Bihar, a jubilant Modi went down to the party headquarters and blew the bugle for the next battle: the once-unattainable Bengal, a place that loomed like something foreign to the BJP—nothing short of what poets once called ultima Thule.

ALSO READ: Nandigram, Ground Zero

But no longer. It will be a bloody battle for sure, but it’s a measure of real progress to be in that battle at all! The party, Modi declared that day, was ready to bring down Mamata Banerjee’s bastion. He had a sure sense of how momentous this was. Between exultations on Bihar and high dudgeon over the “dance of death” in West Bengal, Modi took a moment to reminisce about when the BJP was a “two-seat, two-room” party and how much it has come from there. And it’s precisely within this metaphor of horizontal growth that the Prime Minister set the narrative for all five states due for polls.

And no surprises, he will do the honours on the frontline: Modi is both the advertisement and the product. Over 20 Modi rallies are scheduled in West Bengal alone over its eight-phase election, and half-a-dozen in Assam. Union home minister Amit Shah and president J.P. Nadda are likely to address 50 rallies each, other senior leaders, Union ministers and CMs will do duty too. “The prime minister remains our campaigner-in-chief. His presence works wonders for the party. His rallies and those by Amit Shah will ensure a conducive atmosphere for the party,” says Rahul Sinha, senior BJP leader and former state president of West Bengal.

ALSO READ: Brahmaputra’s Undertow

But while the party plans a blitzkrieg like never before in all poll-bound states, there’s a perceptible differentiation that shows where it imagines itself to be in with a real chance: Modi is expected to limit himself largely to West Bengal and Assam. Shah and Nadda will campaign extensively in the southern states too. The party has organised cadres from all over—Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, UP, Karnataka, Telangana—as footsoldiers. But the focus is clearly Bengal. Mamata, for all her thundering bravado, seems a bit flustered by the BJP’s ambitious and meticulous onslaught. The saffronistas seem to sense they are on the verge of a historic outing.

Tamil Nadu and Kerala are a different matter, of course, galaxies still further away for this voyaging juggernaut. But even there, saffron is no more the inconsequential also-ran it used to be. In sundry, tireless ways, it has registered its presence. While power is a remote prospect, it has inflected the narrative here in key ways. The work is tactical and future-oriented. “Ten years ago, did anyone give us even a fighting chance in Bengal, or Assam?” asks a BJP general secretary. “When Mamata dislodged the Left Front in the state in 2011, ending their 34-year-rule, our party had drawn a blank, with only four per cent votes. In the Lok Sabha, the party had just one representative—late Jaswant Singh from Darjeeling. And the Congress was well-entrenched in Assam. Look at the situation today.” The party is going into the Bengal polls as the main opposition party, as a real challenger. It also won 18 of the state’s 42 Lok Sabha seats in 2019, with a mammoth voteshare of 41 per cent. It had won only three of the 294 seats in the last assembly polls in 2016, but not even Mamata would imagine that to be the scenario this time.

ALSO READ: Saffron Spritz In Dravida Land

Assam, the first Northeast state where the BJP came to power in 2016, is a holding operation. The CAA-NRC controversy came almost like a self-goal by the BJP in Assam—a mismatch between its notions and those of the Assamese became quite tangible, making things more complex. But the chessboard is rife with action. “If the Bodoland People’s Front (BPF) has walked out to join the Congress-led UPA, the party has got a new partner in United People’s Party Liberal (UPPL). The party’s strategic brain is always working,” explains the leader. Baijayant Jay Panda, party vice president and Assam in-charge, insists the BPF walking out will not make much of a difference to the NDA. “The UPPL has emerged as the party that the Bodos trust. The BJP contested the elections to the Bodoland Territorial Council along with the UPPL (in December 2020) and won, forming the government there,” he tells Outlook.

Whenever BJP leaders talk of the party’s “strategic brain”, the allusion is mostly to Amit Shah, who set the BJP’s expansion in motion as its president soon after the 2014 Lok Sabha win. He authored the ambitious ‘Coromandel Plan’—aimed at growing roots and branches across the coastal states of Bengal, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Kerala, besides Telangana. Firming its grip on Karnataka, the one southern state where it has known growth since the ’90s, was part of the plan, but the real fruit it desired was those hitherto unchartered territories. The idea was to finally live up to the old ambition of being pan-Indian—present from Kamrup to Kutch, Kashmir to Kanyakumari. The ‘Plan’ was set into motion at the June 2016 national executive in Allahabad. These states were desirable in themselves, but also important at that stage from the point of view of ensuring a bigger Lok Sabha win in 2019. “The plan was prepared keeping the specific state sensitivities in mind, and has been implemented down to the last detail, no matter how small or seemingly insignificant,” reveals a BJP leader, involved in expanding the party footprint in Kerala. In 2016, the BJP managed a 15 per cent voteshare, seen as a positive sign by party leaders even if it won them only one seat in an assembly of 140.

ALSO READ: Dry Run In Wet Pondicherry

Anirban Ganguly, director of the Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation and West Bengal BJP core committee member, says Shah, as party president, had intense focus on the states, travelling there frequently since 2017. Ganguly, co-author of Amit Shah and the March of BJP, explains that Shah’s presence catalysed the party organisation and charged up the local political atmosphere everywhere. “The organisation grew exponentially in Bengal in the past five years, with systematic restructuring, regular programmes and training. Now it’s ready from booth upward to take on the TMC.”

Rajya Sabha member Vinay Sahasrabuddhe, who too worked on the party’s expansion and membership drive, says a main reason for the BJP breaking new ground is the seriousness with which it fights all elections, whether it is for the Hyderabad municipal corporation or the Lok Sabha. “It doesn’t think of any election as big or small and fights each with all the strength at its command. This resoluteness galvanises the cadre,” he says. “There also needs to be a lofty goal behind the politics, an ideology that keeps the cadre going.” India’s population has enough numbers of the disaffected who would not share that enthusiasm for saffron ideology, but its electrifying appeal to those it does speak to cannot be doubted. Or its capacity to swell the flock.

ALSO READ: A Soft Right To Move Left

Besides ideology, there’s also hard-nosed pragmatism. When it comes to choosing the right person for the right job, it does not hesitate to look beyond the saffron’s homegrown stock. “Bringing in Himanta Biswa Sarma from the Congress to be the BJP pointsperson for Assam and rest of the Northeast turned out to be one of the best decisions,” says a party leader. Indeed, defections from other parties have become a key method in the party’s growth. “The BJP didn’t have a strong cadre in Bengal, but it has managed to woo crucial leaders from the TMC, who have helped in establishing and strengthening the organisation. Mukul Roy, one of Mamata’s closest aides, was the first big catch for the BJP in 2017. He has played a big role in helping the BJP understand the state, its communal faultlines and the TMC better,” he adds.

Sources tell Outlook that it is Roy who helped the BJP’s state in-charge Kailash Vijayvargiya build up the party in the state. It is this duo that managed to wean away top-rung TMC leaders, including Suvendu Adhikari, who is now taking on Banerjee in Nandigram. Vijayvargiya, handpicked for Bengal by Shah in 2015, has been slowly but surely polarising the narrative, picking on the state’s communal faultlines. “It’s a task the BJP has been doing over the years—calling out Mamata for appeasement politics, strategically raising the CAA-NRC issue, even calling infiltrators ‘termites’. It seems to be working in the party’s favour,” explains a Union minister, alluding to a controversial remark made by Shah in 2019.

ALSO READ: A Big If In Its Ifs And Buts Tides

Party leaders believe even Tamil Nadu and Kerala will see a similar turnaround for the BJP’s fortunes in the future. “It’s just a matter of time. The BJP has a lot of patience to see its dream of breaching the Vindhyas come to fruition. PM Modi, Amit Shah and Nadda have all visited Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Politics in southern India is completely different from what a north Indian party is used to, but then the BJP is figuring out what makes voters there tick,” says a central BJP leader, who is coordinating with ally AIADMK. That allyship is crucial for now; it has a touch of proxy rule to it. But the BJP’s gameplan is to eventually have Dravidian politics cede some space to the nationalist BJP. With the two towering political personalities—M. Karunanidhi and J. Jayalalitha—gone, there is indeed space. How that is to be accessed remains the question. “But the BJP is in for a long-term game here,” says the leader. He is confident, though, of the BJP managing to form a government in Pondicherry since the Congress is almost decimated there. “That in itself will be like having a toehold in Tamil Nadu,” he says.

It is Kerala that continues to confound the saffron party. Despite the RSS having a very strong and old base in the state, the people don’t appear to be warming up to the BJP. The social and political segmentation of Kerala is such that a voteshare increase, and a modest takehome in terms of seats, is the maximum the party can hope for.

“We have tried inducting popular actors, police officers and bureaucrats, but the voters don’t seem enamoured by them,” says the leader. Yes, as elsewhere, it has inflected the narrative there. Both the Left and the Congress now respond politically to debates set by the BJP. But come April, Kerala is likely to remain as the next ultima Thule.