The Supreme Court ruled recently that “there is no fundamental right which inheres in an individual to claim reservation in promotion”, and that “no mandamus can be issued by the court directing the state government to provide reservations”. So, have reservations been interpreted in the spirit of Articles 14,15 and 16(4)—the last specifically dealing with the right to equality of opportunity in employment? How have entitlements as justiciable fundamental rights and non-justiciable directive principles been interpreted juridically over the years? Can directive principles impose an obligation on the State to realise the citizen’s entitlements, thus giving the Constitution, as Babasaheb Ambedkar held, a transformative potential? Are fundamental rights discretionary, as this Supreme Court verdict suggests, and hence the State has no obligations? Underlying the verdict are ideas of ‘merit’ and ‘efficiency’, a social debate finding interpretations in varied juridical pronouncements going back to the 1960s, and which gained strength in the discourse around anti-Mandal Commission agitations. It pits individual mobility against class entitlements (of scheduled castes, in this case) and the State’s need to identity ‘legitimate claimants’. The verdict also said there is no justiciable right or constitutional duty to provide reservations, thereby reducing substantial equality to formal equality against the spirit of the Constitution.

There has been a steady erosion of fundamental rights and constitutional principles by varied judgments on reservations. For example, a five-judge constitution bench in the M. Nagraj case (2006) held that states were bound to provide quantifiable data on backwardness of scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, inadequate representation in government jobs and overall administrative efficiency before providing quota in promotions. Various state governments sought reconsideration by a larger bench as the verdict placed unnecessary conditions overlooking the stigma of caste and presumed backwardness. One of those who opposed quota in promotions argued that the presumption of backwardness vanishes once someone joins government service, and that quota can be continued for class IV and III services, but not for higher services. Turning down an appeal by the Centre, the Supreme Court in September 2018 upheld its 2006 order that said quota in promotions was not mandatory in public sector jobs. The court asked why the idea of ‘creamy layer’ used for OBCs could not be applied to deny quota in promotion to the ‘affluent’ among SCs/ STs. There was an assumption that these communities are not entitled to social mobility, and that social mobility meant discriminatory attitudes did not persist.

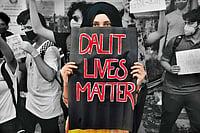

We need to look at reservations for SCs/STs in promotions from two levels—judicial pronouncements and political developments. In April 2, 2018, a Bharat Bandh called by Dalit organisations against dilution of the stringent provisions of the SCs/STs (Prevention of Atrocities) Act (POA Act) of 1989 by a Supreme Court order evoked wide response from Dalits and India witnessed an unprecedented mass protest, peaceful but for a few clashes with elite castes. Through a well-publicised parliamentary session, the Centre decided to restore the original provisions of the law, and the Supreme Court, on an appeal by the central government, recalled the verdict that had diluted it.

There has been apprehension that constitutional rights are being eroded and that reservation itself could be removed. The floggings in Una, Gujarat, and other atrocities on Dalits energised varied Dalit sub-castes and organisations to unite, with the youth and students in particular mobilising around the suicide of Rohith Vemula in Hyderabad. Broader alliances are being forged, and what were considered ‘sectional’ issues are more and more leading to wider solidarities on citizenship, rights and constitutional principles, with the Dalit movements, youth in particular, providing the leadership. The Bhima-Koregaon case too is linked with counter-cultures and growing solidarities among marginalised sections—Dalits, Adivasis, Muslims et al. Chandrashekhar Azad’s recent detention for participating in anti-CAA protests is a pointer. Responses to court verdicts, including the recent one on quota, will no doubt be inter-sectional in approach, given the nature of ongoing protests in different parts of the country.

(Views are personal.)

Meera Velayudhan,Kochi-based policy analyst