If a layperson was asked how she would visualise a ‘court’ to be, she is likely to describe a court-hall with a judge sitting on a pedestal, lawyer/s presenting arguments or examining a witness, and perhaps other litigants and lawyers waiting their turn to be heard. Seldom, if at all, will anyone identify a court with its various other paraphernalia beyond the court-hall.

The court registry, comprising the filing, scrutiny, process-serving, pending and other branches play a direct and critical role in the manner in which a case progresses through the justice system. Yet the popular imagination of what a court is and does remains confined to a ‘courtroom’. What happens behind-the-scenes remains strictly there—behind the scenes. This lack of visibility, clarity and knowledge about the roles of actors beyond the judge acting in her judicial capacity is arguably the primary reason why the judiciary’s historical problems—pendency, delay, uncertainty, cost and time inefficiencies—continue to remain and worsen.

ALSO READ: Free Or Fettered?

The ‘administration of justice’ requires the coming together of both the administrative and judicial components of our justice system. Justice cannot be equated to just the judgment or an order given by a judge; it is an experience too and hence the aphorism: not only must justice be done; it must also be seen to be done. Take, for instance, the murder case of Sister Abhaya, decided in December last year by a special CBI court in Kerala’s Thiruvananthapuram. It took the court 28 years to finally convict the accused persons. Would this conviction, assuming it gets upheld by the appellate courts, constitute justice? Is the delay at every stage of the case, right from filing of FIR, investigation, witness examinations, et al balanced out by a judgment that ultimately resulted in a conviction?

To be fair, the travesty of justice in the Sister Abhaya case is attributable not just to the courts but equally to the other components of the criminal justice system, such as the police and other investigative agencies. But then, even in civil cases where the court is not dependent on such ancillary systems, extreme delays are a norm. As per the NJDG data, there are around 40,000 and 75,000 civil cases pending in the district judiciary and High Courts respectively for more than 30 years.

Arnab Goswami after his triumphant release on bail.

So far, judicial delays and most other problems with the judiciary have been explained away by citing the lack of quality and number of judges and/ or the attitude of lawyers seeking adjournments. This has restricted the focus entirely on the judicial side of the justice system. It is, therefore, imperative to shift attention to the administrative side, wherein lie the deep-rooted, systemic issues.

ALSO READ: The Supreme Court A Long Political Journey

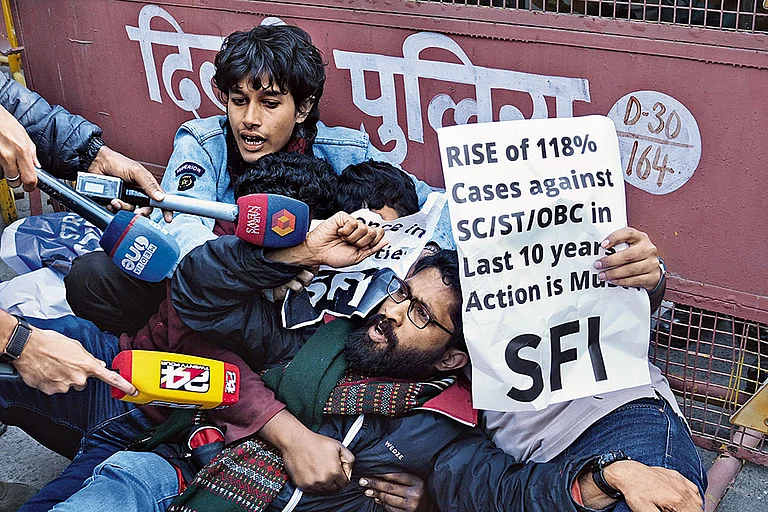

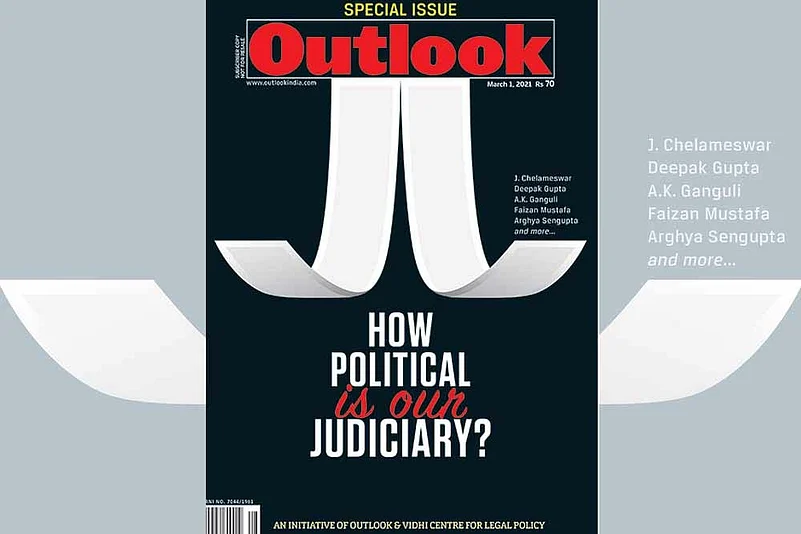

Unfortunately, these systemic issues come to fore as aberrations, whenever public attention is drawn to them through a ‘celebrity case’. Take, for instance, the recent uproar over an urgent listing and hearing granted to Arnab Goswami’s bail petition (defective at that) before the Supreme Court. A section of the media and the public were quick to conclude that this was on account of politicisation of the judiciary. Without going into the merits of such charges, what was lost in the din was that on an everyday basis, such seemingly ad hoc and unjustified decisions are taken regarding thousands of cases. These administrative decisions, especially the ones regarding non-listing of Constitution Bench cases or habeas corpus petitions have as much bearing on the life, liberty and property of individuals as the ultimate judgments. However, there is lack of visibility as regards the parameters or processes guiding these decisions. Worse still is the fact that unlike judgments, these discretionary administrative decisions are not even up for appeal.

It is for these reasons that demands for quality, transparency and accountability which have so far been limited to judges, must now be extended to judicial administration. It is not common knowledge that the judges, at all levels of judicial hierarchy, are responsible not just for managing and deciding cases but are also administrative heads of their individual courts. Depending on their seniority, they also discharge various administrative responsibilities related to recruitment, infrastructure, technology integrations, procurement and other court management systems. Given how ferociously the judiciary guards its independence, its administrative structure is designed such that all decisions are supervised and ultimately signed by a judge.

ALSO READ: Collegium Collateral Damage

This concentration of administrative and judicial duties in a judge creates a massive capacity constraint. Added to this is the fact that these judges are not really trained to undertake managerial functions. Further, a judge is a master of her court-hall and is free to manage her caseload, devise processes for day-to-day functioning and supervise her staff as she deems fit. Even though broad guidelines do exist in the form of rules, notices and circulars, a vast amount of discretion is vested with the judge.

Given this, it would be fair to say that no two courts in the country function the same way. For instance, a study by Vidhi and DAKSH on Bangalore Rural Courts highlighted the differential practices that exist even between judges of the same cadre tasked with similar case categories. While one judge listed just around 52 cases, the other listed more than 100 cases a day. One judge allowed mentioning of urgent matters in open court; another insisted on a written memo. There were differences even in terms of how often and how extensively data from individual courts was updated onto the eCourts system. By corollary, this also means that no two litigants have similar experiences with the judiciary.

Consistency and predictability are the bedrock of any fair system and, evidently, the current judicial administration fails to guarantee these. The lack of expertise combined with vast discretionary powers has done serious damage to the credibility of the judiciary as an institution.

Vesting administrative discretion with judges was not without its merits. In the era where data was scant, judges were the only ones who were fully aware of their case docket and the various demands on their time. However, with greater infusion of technology and availability of data now, it is possible to devise a more predictable system based on relevant parameters. It is equally critical that these parameters be made public to ensure transparency and bring accountability to an otherwise opaque system. This is one sure way to increase trust in the judiciary and reduce the frequency with which ulterior motives are ascribed to it.

(Views expressed are personal)

ALSO READ

Deepika Kinhal is a senior resident fellow at the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy