Imagine choking on a morsel of food and gasping for air—that rencounter with death most of us have had at the dining table at some point in our life. The Heimlich manoeuvre may save you from that stubborn crumb stifling your windpipe. Now, scale that choker several times up. What happens when your lungs, battered and heavy with fluid from an infection, struggle to pump air and process the amount of oxygen required to keep your body fully functional, and let you be a living, breathing human? You need oxygen—pure, medical grade—from a respirator, from a ventilator, from a cylinder. What if this oxygen isn’t available, like it happened when the second wave of the Covid pandemic peaked in April-May in India, overwhelming our healthcare system? Death—slow, painful and wretched, like a fish yanked out of water.

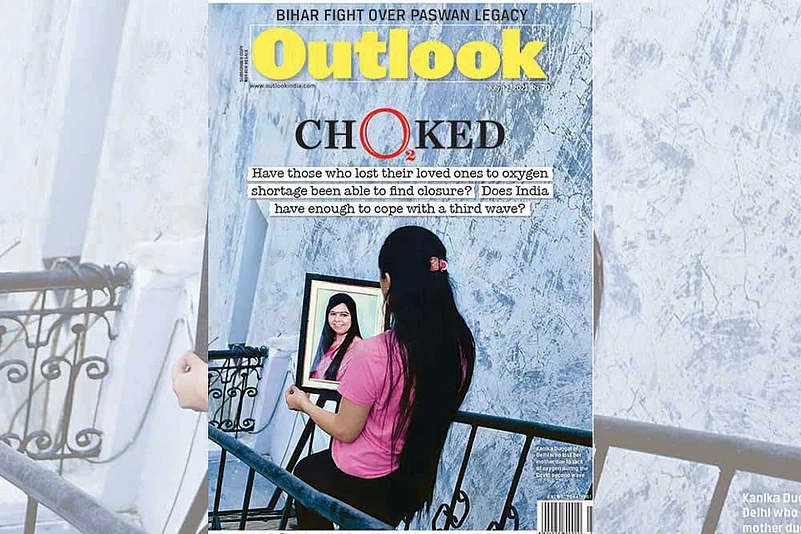

We have seen it during the month-long carnage—thousands dead begging for a breath, heart-wrenching scenes in hospitals, their emergency units and carports. A daughter tries to revive his father by pressing his chest with her folded palms. A wife gives mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to her husband, fully aware she would be infected too, if not already. An inconsolable woman refuses to leave her husband’s corpse. A father pleads with a doctor for an ICU bed for his son. A man begs a patient to share his oxygen cylinder with his younger brother. They died of Covid, but it’s the lack of oxygen that killed many. What do you call it when a soldier dies of a gangrened bullet wound? The bullet killed him, or the sepsis? Both, actually. Depends on how one quarters and fillets the cause of death, and fills out the official report. Hundreds of deaths in the coronavirus pandemic followed this order: Covid, oxygen shortage. There are other factors, but for the context, oxygen is the least we should be able to provide to save lives. So then, are we prepared if there’s a third outbreak?

ALSO READ: Don’t Foul Our Oxygen

Yes, we are trying to make amends. But it’s also paradoxical that we are also running into a row over an oxygen audit report from the second wave. A Supreme Court-appointed four-member committee reported that the Delhi government of Arvind Kejriwal marked up its oxygen requirement four times more than the city needed. The Centre and AAP’s political rivals inveighed against the Kejriwal government for inflating Delhi’s oxygen figures when the entire nation was staring at a crisis. The Delhi CM has denied the charges, while experts found holes in the committee’s findings. For instance, the report doesn’t break down the daily demand for and use of oxygen in each hospital. They ask: If Delhi had excess supply, why were hospitals like Fortis and Max sending SOS from their Twitter handles, asking authorities to fill their oxygen tanks and warning that hundreds of patients are at risk? “Is this the lesson our politicians learnt from the disastrous second wave?” wonders Rahul Bhargava, head, haematology, Fortis Hospital, Gurgaon.

ALSO READ: Candle In The Wind

If politicians were trying to stir controversy, they succeeded. There’s no point cleaning the mirror when the dirt is on the face. But that doesn’t answer the basic question: Are we prepared? To answer that, we must know the dynamics of factory-produced oxygen. Liquefied medical oxygen (LMO) is a byproduct of the gas produced and used in industries, mostly steel. Only 10 per cent of the gas is used for medical purposes, the rest is for industrial use. Companies like Linde, INOX and Air Liquid have plants that suck oxygen from the atmosphere, compress it into its liquid form and supply it to industries, especially steel plants. Oxygen production is not uniform across the country. Only 13 per cent is produced in north India and 22 per cent in the southern states; the east and west account for 65 per cent of the total production because the majority of industries that use oxygen are located in these belts. “The current capacity of Odisha is three times that of oxygen consumed during the peak first wave of Covid-19,” says Dr Bibhudatta Mishra, paediatric intensivist, Jagannath Hospital, Bhubaneswar. The immediate need during the second wave was not to crank up production, but to divert oxygen supply from industries to hospitals. That involves a logistic challenge—like shipping LMO in tankers from oxygen-rich areas to deficient states. Highlighting the demand-supply mismatch during the second wave, a government statement informed: “One-third of the production is concentrated in east India, while 60 per cent of the demand for oxygen is in north and south India, resulting in transportation challenges.” To avert a crisis similar to the disaster in April-May in case of a third wave, health experts suggest diverting all oxygen for medical use for the time being and strengthening the supply chain to make it seamless. It is highly likely that oxygen could be at the centrepiece of our fight against Covid if another outbreak hits us.

ALSO READ: With A Gasp, They Left Us

Hospital data from across India show a 10-fold increase in demand for oxygen between April 15 and May 15. For instance, Lok Nayak Jai Prakash Hospital (LNJP), the biggest hospital in Delhi with 2,000 beds, has a daily requirement of 4 MT on normal days. “In the second wave, we converted all beds into oxygen beds and our peak demand was 37 MT, nine times more than our daily requirement. This includes oxygen cylinders ferried to banquet halls that were converted into makeshift hospitals,” says Suresh Kumar, medical director, LNJP. In Fortis, Bhargava says, the daily requirement was five times higher—from 1 MT to 5 MT—during the period. Similarly, the owner of a medical college and hospital in Rajasthan, who doesn’t want to be identified, says his daily requirement increased 10 times—25 jumbo cylinders in pre-pandemic times to 250 cylinders a day when the Covid caseload spiralled out of control this summer. Medium and small hospitals don’t have any storage tanks for LMO. They use cylinders.

ALSO READ: Oxygen

The Centre has told the Supreme Court that the demand for medical oxygen averaged around 5,500 metric tonnes a day in the third week of April, rapidly increased to 7,100 MT in the fourth week, and peaked at 8,943 MT on May 9. The sudden spike in demand caught the government off-guard. The Centre ordered manufacturers on April 18 to stop supplying oxygen to non-medical industries from April 22. In late April and early May, the government took several steps to augment production and strengthen the distribution network. It asked steel plants that produce oxygen for internal consumption to help. It was a delayed response, health experts say, and should have been taken in the first week of April. By then, hundreds had died.

A new oxygen tank in Gauhati Medical College and Hospital

Preping Ahead

The Centre-appointed national task force (NTF) for Covid has recommended monitoring oxygen needs in hospitals by setting up a monitoring committee and optimising need. It suggested an oxygen grid with 10-12 regional production sites for exigencies. The suggestions include storage hubs for any situation, streamlined long haulage through trains and trucks from plants to storerooms, and that all 100-bed hospitals with 25 per cent ICU beds must get 1.5 MT of oxygen each day. Besides, states are asked to create a real-time dashboard to monitor supply and demand. The NTF also recommends setting up field hospitals near oxygen production units, making oxygen generation units compulsory for all hospitals, maintaining a strategic reserve for the country to cover at least three weeks (on the lines of petroleum products), and a strategy to produce oxygen in and around big cities—especially Delhi and Mumbai, “due to their population density”.

ALSO READ: Delta Is The New Alpha

For its part, the Centre says it has started work based on the NTF’s recommendations—of the 162 plants with a capacity to produce 154.19 MT in 32 states and Union territories, 147 were delivered, 117 plants installed and 115 are generating oxygen. All these plants will be commissioned by June-end, it says, and promises that 1,600 units will be installed in all. “States are also developing comprehensive medical oxygen plans and strengthening infrastructure for medical oxygen in the public and private sectors. Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Telangana, Uttarakhand, Kerala, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan have finalised their plans,” the Centre says.

Health experts praise the measures, but with a pinch of salt. “The initiatives are praiseworthy, but we cannot rely on plants that run on electricity. We need to have a good backup,” says Dr Ravikant Singh, founder of Doctors For You that ran four Covid-care centres in Delhi. “Also, we have to keep in mind every little product that acts as a supplement, and without that the whole exercise remains futile. You will be surprised that despite augmenting oxygen production and supply, there is a shortage of flowmeters.” It is the device that takes oxygen from a cylinder to the patient, and measures the volume of gas released. NTF member Dr Bhabatosh Biswas, who is also chairman, board of governor, National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research (NIPER), agrees that “we need a backup plan”.

Oxygen-producing companies call the plan to set up plants a waste of resources. They say the need of the hour is to augment LMO storage capacity in hospitals, rather than installing plants that will produce oxygen in the gaseous form. “Take Fortis as an instance. It needs 1 MT of LMO in normal days and needed 5 MT during the second wave. So, it will install a plant for 1 MT. When the demand rises to 5 MT, what will it do? It will have to go to the companies. Also, these machines need a lot of technical support,” says a senior official with a company. “If your backup is LMO stored in tanks, why cannot they make a one-time investment and increase storage capacity. Why do we need a plant if your primary source is LMO?” An official of another company argues that Delhi would have never faced any oxygen shortage if it had two storage tanks of 5,000 MT—each the size of two lawn tennis courts. Dr Singh of Doctors For You agrees that storage needs to be increased. He cites Bihar as an example. A state close to the industrial belts faced oxygen shortage because it doesn’t have adequate LMO storage facilities. “Bihar couldn’t use its share of oxygen given by the government because it didn’t have any place to store that much LMO,” he says.

Experts also warn that medical colleges and hospitals might pass the cost of installing and operating plants to patients and students. “We need lakhs of technicians to operate these and staff to run it. Who will bear the cost? The people of India, obviously,” says a senior doctor with a private hospital. The people of India have paid a heavy price already because of an old, chronic infection: The country’s derelict public healthcare system, and half-hearted approaches to lift it from the pits.

***

Act III: A Probable Scenario

Lok Nayak Jai Prakash Hospital (LNJP), Delhi’s biggest hospital, needed 37 MT of oxygen for 2,000 patients on a single day when the Covid second wave peaked. Based on this consumption, if we calculate the oxygen requirement for 1 lakh patients a day, presuming that a third outbreak will be more severe than the second, the daily oxygen requirement goes up to 1,850 MT a day. So, for 10 days of storage, Delhi needs 18,500 MT. Tanks of 5,000 MT at four places in Delhi can provide 20,000 MT of oxygen. But the challenge will be human resource. Do we have enough doctors, paramedics and nursing staff?