The Supreme Court of India has often been described as the most powerful court in the world. The court no longer remains just a court of law, but has gradually transformed into an institution of governance. In its 71-year-long history, and particularly the post-Emergency years, the apex court has emerged as a forum that hears a plethora of disputes, offers a range of remedies, and makes observations that impact politics in the country.

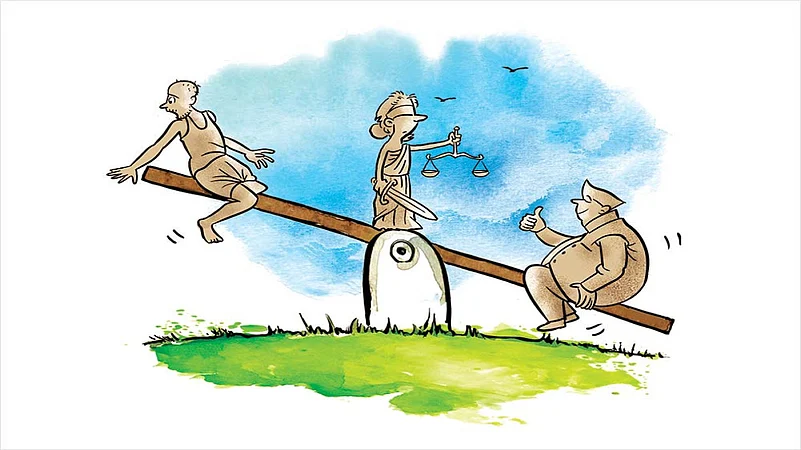

Of the many grudges held against the Supreme Court, one that dominates contemporary public discourse is the “politicisation” of the judiciary. This allegation is premised, in part, on how often the judiciary decides in favour of the executive of the day (where the government is a litigant). At times, this allegation also stems from the refusal of the court to hear seemingly pressing political cases involving the government. At other times, the Supreme Court opens itself to an apprehension of politicisation because of the wide expanse of matters it hears and the lasting impact of its judgments.

ALSO READ: Free Or Fettered?

If Richard Posner’s understanding of “political issues” is to be adopted—issues about political governance, political values, political rights and political power—then it would be difficult to argue that the Supreme Court of India is not a political institution.

A linear narrative of the Supreme Court generally pinpoints to the court touching its nadir in ADM Jabalpur (1976), and then gradually emerging as the public interest litigation (PIL) court in the 1980s. Several factors—including relaxation in the rules for approaching the court, expansive interpretation of the word ‘life’ under Article 21 and development of ingenious remedies—positioned the Supreme Court as readily available to redress the grievances of the masses.

ALSO READ: The Supreme Court A Long Political Journey

However, the Supreme Court’s far reach into the democratic discourse is not limited to only fashioning innovative remedies in PIL cases. Subtler, but just as pertinent, are the Supreme Court’s observations that show how its rulings shape Indian politics. Take, for instance, S.R. Bommai (1994), where the court dealt with the justiciability of the presidential proclamation of emergency in a state, and the extent of judicial review. The judgment stated that there must be cogent and credible reasons for dismissing a state government. Bommai, while pronouncing on aspects of federalism, has inevitable implications for the politics of Centre-state relations. Its political impact was clear—there is now a marked decrease in the imposition of President’s rule in states.

The Supreme Court has also, on occasion, commented on the realm of political life in India. While deciding whether an appeal to ‘Hindutva’ or ‘Hinduism’ in election speeches amounted to appeal on the ground of religion (Ramesh Yeshwant Prabhoo, 1996), Justice J.S. Verma explained Hindutva as a way of life or a state of mind, which is not to be understood as religious Hindu fundamentalism. He likened ‘Hindutva’ with ‘Indianisation’, or the “development of uniform culture by obliterating the differences between all the cultures coexisting in the country”. To an impartial observer, Justice Verma’s understanding of ‘Hindutva’ can appear as a quest for achieving commonality between diverse communities, rather than as an appeal to their religious preferences. But it has largely been seen as a judicial endorsement of Hindu majoritarian politics.

The eventual outcome of this case—the accused were held guilty of promoting enmity between religions by their use of derogatory language for Muslims in election speeches—is, sadly, forgotten.

ALSO READ: Collegium Collateral Damage

The rulings of the court have also deep implications in shaping electoral politics. In 2004, a legislative amendment that removed the requirement of domicile in the state concerned for getting elected to the Rajya Sabha was challenged before the court for violating the principle of federalism. In its judgment, the court expounded upon the respective roles of both houses of Parliament. Per Chief Justice Y.K. Sabharwal in Kuldip Nayar (2006), the Rajya Sabha “acts as a revising chamber over the Lok Sabha”, and “does not act as a champion of local interests”.

The court’s understanding of the role of the Rajya Sabha stemmed from its understanding of Indian federalism. It noted that in the Indian context, the principle of federalism is not related to territory, and it is no part of the federal principle that the representatives of the states must belong to the state. Kuldip Nayar is a crucial addition to the discourse on the significance of the Rajya Sabha, especially considering the numerous calls made for its abolition. It also carries implications for the composition of the Rajya Sabha, and for manoeuvring by political parties on who can be sent to which house of Parliament.

The Supreme Court’s routine forays into governance have also etched fresh boundaries between different tiers of government. The 73rd and 74th amendments to the Constitution (1992), which recognised institutions of local self-government, are characterised largely by their unsatisfactory implementation. The Member of Parliament Local Area Development Scheme (MPLADS), which enables MPs to recommend developmental work in their constituencies, has been criticised for invariably permitting parliamentarians to step on the toes of constitutionally recognised (and locally elected) district and village-level authorities. The scheme is also attacked for unsettling the principle of separation of powers.

In a challenge to its constitutionality in 2010 (Bhim Singh), the court rescued MPLADS on both counts. Significantly, it held that panchayats and municipalities are not denuded of their role by the scheme. Ten years hence, and despite allegations of diversion of funds, the amounts spent on projects under MPLADS in India have only spiralled. At the same time, devolution of functions to local governments, the avowed aim of the 73rd and 74th amendments, remains erratic and non-uniform across Indian states.

That decisions of the Supreme Court have inevitable political consequences does not indicate a direct cause-and-effect. Rather, they demonstrate the overwhelming presence of the court in critical political matters. A judiciary like India’s, so deeply enmeshed in the political goings-on of the country, lays itself bare to allegations of “politicisation”. As Posner points out: political and constitutional issues arouse greater emotion, and emotion can deflect judges from dispassionate technical analysis. The Supreme Court is tasked with interpreting the Constitution, where being political is, more often than not, inevitable. But it is when the judiciary becomes partisan that the real cause of worry emerges.

(Views are personal.)

ALSO READ

Ritwika Sharma is senior resident fellow at the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy