The cancellation of school board examinations presents, somewhat ironically, a window of opportunity to rethink admission procedures and practices for the higher education space. As HEIs (Higher Education Institutes) still wrestle with the tectonic impact of Covid that disrupted established modes of functioning, millions of potential school leavers grapple with the myriad anxieties of uncertain futures. For the freshman undergraduate cohort of 2020, college as a community of learning and collaborative imagination embedded in the collective consciousness evaporated into the experience of the academy as truncated and interrupted. The aspirational context for individual agency dissolved into an alienating mirage.

The online teaching-learning necessitated by Covid lockdowns and HEI closures has had its own sets of challenges, leaving both teachers and students largely dissatisfied. Where education shifted from class to home, students with special needs, women students with care responsibilities, those dependent on ‘work study’ incomes, those waiting to transit to chosen university destination or enter the labour market and those with uneven access to technology, online resources, internet connectivity, suitable physical space to support learning, were disproportionately affected. Given the pervasive class, caste, gender and locational inequalities, the access and equity issues of India’s digital divide surfaced dramatically, compounding social and pedagogical challenges. In the switch to ‘blend learning’, several options and possibilities provided by the asynchronous learning model were left unexplored. In the complex ecosystem of higher education in India, comprising over 1000 universities, approximately 40,000 colleges and around 10,000 stand-alone institutions, with varying levels of resource and infrastructure, the ‘digital panacea’ felt woefully short.

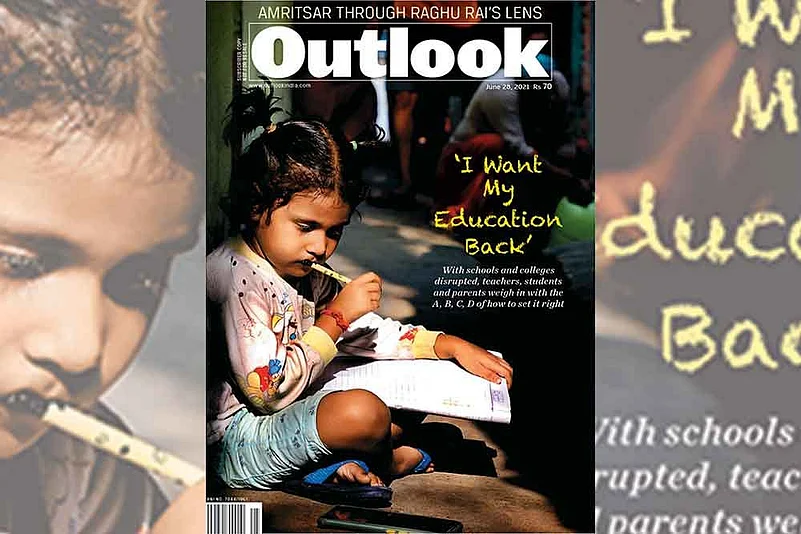

ALSO READ: Give Me Back My Classroom

For a majority of teachers, it involved hurriedly switching from face-to-face teaching to the less satisfying, yet daunting terrain of virtual education. In a large number of HEIs, it translated into collating information from web-sources, disseminating lecture notes through WhatsApp, with Zoom or Google Meet sessions added on for good measure. Educators missed out on the thrill of the shared everyday epiphanies of the proximate classroom space. The flicker of recognition at the acceptance of an idea, the quizzical articulations, the unmediated communication that is the authentic barometer of learning resonance and the spur to motivation—all remained elusive.

Students missed out on other vital aspects of the college experience. The intensity of co-curricular endeavour, the allure of the sports field, the camaraderie of cultural engagement, the life-changing interactions in hostels, the friendly sparring of dialogue and debate, the discovery of unfamiliar worlds, new calibrations of identity, autonomy and freedom, and the tangible lessons in citizenship, bargaining and coexistence—all remained for the most part absent from their canvas.

ALSO READ: Imagining The Post-Pandemic Campus

For the bourgeoning numbers of admission-seekers to colleges and universities this year, who prepare to navigate their aspirations through the labyrinth of sky-rocketing cut-offs, the lack of clarity on the criteria and basis of admission is bewildering and demoralising. The contours of the policies that are currently being contemplated for the HEI space must have the expansion of academic autonomy and administrative decentralisation at its core. This is the opportune moment to invest trust in students and teachers, and ‘de-infantilise’ and decentralise evaluation processes. Innovations like open book exams and grading on learning trajectories rather than sole reliance on an external examination, robust self-regulatory mechanisms with suitable checks and balances should be the default options. The spirit of the much publicised CBCS (Choice Based Credit System) is best served in rendering teaching-learning and evaluation processes flexible and transparent.

ALSO READ: Flight To The Future

Substantive questions about our processes of knowledge production and dissemination—our epistemic structures—need to be addressed. How hospitable are we to the multiple intelligences that diverse learners bring to the academy? How effectively do we break the hierarchies between different disciplines (STEM, social sciences, humanities et al) to accommodate a genuine pluralism of ideas? How open can we be to the not always harmonious reverberations of learning? How do we encourage the easy flow of critical thinking to bear on ‘received curricula’ and course requirements? How ‘constructivist’ are our classrooms and pedagogy?

More than 86 per cent of the 37.4 million students who inhabit the higher education space are undergraduates. The nearly 40,000 colleges added approximately 800,000 students in 2019. Of the 1,059,080 students who passed the CBSE board exams in 2020, 150,000 scored more than 90 per cent; 38 per cent scored more than 95 per cent.

HEIs in India today take pride in the fact that their admission processes are based purely on ‘merit’, and consequently are ‘impartial’ and ‘objective’. Herein lies a contradiction. ‘Merit’ in everyday parlance has become conflated with marks obtained in the board examinations. Between the CBSE, ICSCE, IB and several state school boards, there exist wide disparities in the awarding of marks. Do we need to wait till the average marks awarded by school boards catapult to 99 or even 100 per cent to unscramble what we describe as the ‘merit’ criteria?

The examination-rank method and the ‘merit-only position’, as sociologist Satish Deshpande reminds us, also obscures the causal contribution of pervasive socio-economic inequalities towards the unequal distribution of merit that block access to higher educational opportunities. With the exponential increase in numbers of students seeking admission and the growing demand for one-window procedures to reduce inconvenience, large affiliating public universities, like Delhi University (with over 77 colleges) and Mumbai University (with more than 700), adopted centralised registration processes. They came under persistent pressure to curtail pluralism and diversity, and standardise admission-criteria in the interest of ‘transparency’. In the process, several colleges (other than minority institutes), including the so-called autonomous colleges in the country, either lost or abdicated to their parent universities their crucial role in shaping the selection processes best suited to their own mission, ethos and vision for the future.

The assumption that centralised processes are more ‘fair’ and ‘objective’ is a specious one and remains largely unsubstantiated. A system that fetishises ‘standardisation’ is inherently mechanistic—equipped to plot ‘output’, but impervious to qualitative learning trajectories. Admission processes must be in tune with the imagination of the academy as a ruminative space where students are given a chance at every possible avenue of creative exploration. Evaluations must be done by those who will teach the applicants and are best positioned to assess them.

Mode Swing Teachers try to adapt to new platforms of teaching-learning.

This involves meticulous hard work and cannot be compressed into two frenetic months. The world’s best universities take a year on an average to select and admit students. The UK-based Times Higher Education lists some of the criteria that the top 50 universities adopt when selecting students. In addition to good grades, they include a positive attitude towards study, a passion for the chosen subject, the capacity to work and think independently, to complete tasks, an inquiring mind, good writing skills, an ability to work well with groups and, interestingly, ‘common sense’, among others. Applications are carefully assessed and balanced with ‘needs blind’ and ‘leg-up’ affirmative action processes. The applicant is more than a number. She represents both potential and aspiration.

It is sobering that, of the 750,000 Indian students who have moved on to study in some of the best universities abroad, several may well have been pipped at the ‘cut-off’ post in their own country! HEIs need to envision admission policies that move the discourse beyond the familiar brouhaha of what percentage of school marks, at which grade, will determine their ‘criteria’ of selection. True, there needs to be an appreciation of the continuum of learning between school and college, involving more sustained dialogue between these two domains. Yet, stepping out of school is the rite of passage of a new trajectory involving changed predispositions, skills, aspirations and levels of autonomy.

Admission policies to HEIs have to be cognisant of the uncertainties and disruptions that characterise this millennium, and the need for appropriate skills to negotiate and navigate unanticipated futures. They must expand spaces of agency for the learner in the age of Anthropocene. The Whole New Mind that the future demands, we are told, belongs “with creators and empathisers, pattern recognisers and meaning makers” (Daniel Pink).

As early as 1926, in raising the question of the principle of selection to universities, Bertrand Russell had despaired that they were becoming mere “training schools for the professions”. He reiterated their indispensable role in the creation of an “educated democracy” and fostering the “spirit of adventure and liberty”, “a voyage of discovery” for a generation educated in “fearless freedom”. He added that the pursuit of knowledge as purely utilitarian is not self-sustaining.

Admission and evaluation policies must not lose sight of the expansive vision of the academy as a space for synthesis that nurtures the multi-creative potential of students and encourages them to make connections across disciplines, while harmonising the physical, intellectual, social and aesthetic dimensions. Drew Gilpin Faust, former president of Harvard, had invoked university education as “learning that moulds a lifetime, learning that transmits the heritage of millennia and that shapes the future” where knowledge is pursued in part, because it defines what has over the centuries has made us human, not only because it enhances our global competitiveness. Now more than ever before is the time to fashion a new conceptual vocabulary of engagement that enables young learners to connect with the ruminative, democratic, inclusive, dialogic and intellectual promise of the academy, and expand the canvas of aspiration.

The purpose of education is also to “turn mirrors into windows” (Sydney Harris) to move the compass from immediate crisis to long-term opportunity. If the true voyage of discovery then, as Proust says, lies not merely in seeking new landscapes, but having new eyes, let us not miss the wood for the trees.

The writer is director of Women in Security, conflict management and peace (Wiscomp) and principal emerita of Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi. Views expressed are personal.