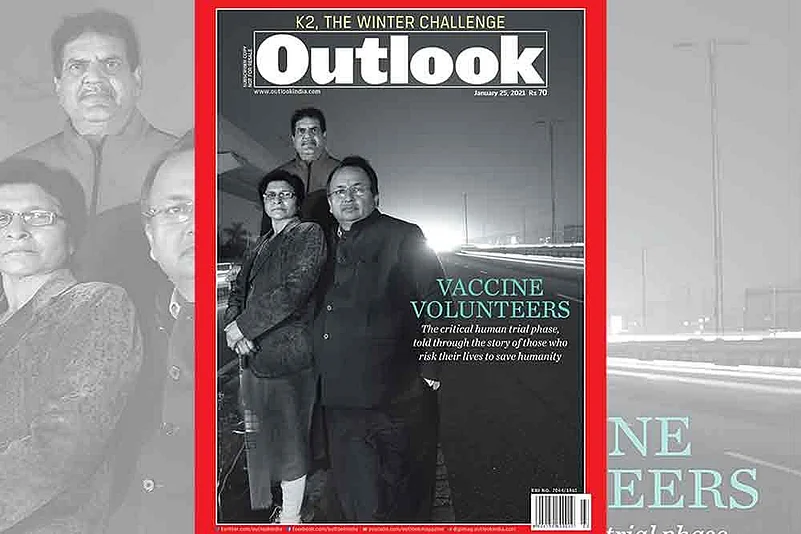

Heroes are not always born. They are sometimes made—ordinary men and women moulded into steel by the need of the times, when humanity faces its sternest test. Like a pandemic. Like today. And these are no cape-wearing crusaders. Just the man next door. Or a young engineer. Even a student. Like Pratibha Jain, 25, of Jaipur. Or 50-year-old Santosh K. More, a Pune-based CSR consultant. And many more who have put up their hands in the search for an effective vaccine against the coronavirus; these are the people who volunteered to take the shots in the crucial human trial phase that measures the effectiveness of a new treatment.

New drugs or vaccines go through rigorous tests and evaluation on animals and then humans before reaching regulators for approval. In 1955, when American virologist Jonas Edward Salk developed one of the first successful polio vaccines, his entire family volunteered for the clinical human trials to determine the efficacy of the medicine. Behind the success of every drug developed successfully are a group of selfless people who brave the unknown to volunteer for the trials.

ALSO READ: Voluntary Service

The world may have finally found the miracle drug to beat the deadly COVID-19 virus which has claimed nearly two million human lives globally but it has been a long and painful journey for groups of dedicated scientists and volunteers engaged in the development of the wonder drugs. And as the first batches of vaccines roll out across India, it’s perhaps pertinent to tell their stories. The stories of ordinary men and women who have emerged heroes in the face of adversity and brought hope to millions of their fellow-countrymen.

Making of a vaccine

Developing a vaccine is a long and winding process, involving several stages. After testing the safety and efficacy of a vaccine on animals, it is tried on humans in four phases. The biggest challenge is in finding healthy persons who would take the initial shots, despite the risk of side-effects which can, in extreme cases, even lead to death.

ALSO READ: Tried And Tested

According to the New Drugs and Clinical Trial Rules, 2019, the first phase of human trials test the safety and tolerability on a very small group of volunteers; the second phase assesses effectiveness on a comparatively larger group, and the third phase confirms the finding of phase II on a much larger group of participants. The fourth phase is post-marketing trial after the drug is approved. Normally, patients who suffer from severe and life-threatening diseases such as cancer offer themselves willingly in clinical trials of different cures.

“Drugs for life-threatening diseases are very expensive and cost in lakhs (of rupees). So many patients participate willingly because they get highly expensive drugs free of cost along with medical care at trial stages. They have no other option,” says a principal investigator (PI) of one of the 14 hospitals in which the Serum Institute of India conducted the trial for its Covishield vaccine. “However, for COVID-19 vaccine, we needed healthy adults as volunteers,” he says, requesting anonymity as PIs are not authorised to interact with the media.

Adults with co-morbidities like blood pressure and diabetes can participate in the trial but doctors say that finding such volunteers was equally challenging in the initial stage of vaccine development. “Though COVID-19 caused many deaths, none faced a life-threatening situation unless infected and few therefore felt the urgency to step forward,” the PI adds, highlighting the shortage of volunteers in the months of August when the trial started.

From August onwards till date, in just four months, over 24,000 people have voluntarily come forward for the clinical trials of two vaccines—Covishield by the Serum Institute of India (SII) and Covaxine by Bharat Biotech. The Drug Controller General of India (DGCI) approved both the vaccines on January 3 as effective and safe protection against COVID-19. At least 1,600 volunteers were recruited in 14 hospitals for Covishield’s clinical trials in India; these hospitals are located in Visakhapatnam, Pune, Mumbai, Patna, Chandigarh, Nagpur Chennai, Sewagarma and Vadu. The first enrolment took place from August 24.

The All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Delhi, which was also supposed to conduct the trial, couldn’t do it due to delay in the process of approval. “By the time we got ethical clearance and were ready, they had completed the required sample of subjects,” AIIMS director Dr Randeep Guleria tells Outlook.

Clinical trials for Bharat Biotech’s Covaxine is ongoing in 26 hospitals—both state-run and private—across the country, including in smaller cities like Jajapur and Sangali besides Mumbai, Delhi and Hyderabad. According to a DCGI’s statement about Bharat Biotech’s clinical trial, “The Phase III efficacy trial was initiated in India in 25,800 volunteers and till date, 22,500 participants have been vaccinated across the country…”

Dr Jugal Kishore, head of Community Medicine in Delhi’s Safdarjung Hospital says that “diversity” in volunteers’ samples provide better data and understanding about the safety and efficacy of the vaccine. “The response of a vaccine varies due to differences in ethnic, geographical, social and financial background of recipients,” he says, adding, “That’s why efforts are made to run the trial in hospitals at different locations.”

Besides these two, there are more than half-a-dozen other vaccines at different stages of trials. Prominent among them are the Russian vaccine Sputnik V and ZyCoV-D by Indian firm Zydus Cadila. According to a source in DCGI, there are 350-400 clinical trials—some of them completed—on COVID-19 in India which are studying different aspects of the virus. The trials include ayurvedic medicines as well.

Fear is the key

People involved in vaccine development admit that it was difficult to find volunteers in the initial stages, mainly because of the fact that they were faced with an unknown virus and that predictions about the progression of the disease by internationally-acclaimed experts had gone completely wrong. “This led to an erosion of trust of people in the process of vaccine development and that’s why initially finding volunteers was difficult,” an investigator says. However, many investigators say that once the news spread about the need for volunteers in hospitals people came forward in large numbers.

Dr Sanjay Lalwani is head of the Department of Paediatrics at the Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University Medical College and Hospital, Pune. The hospital has been doing clinical trials of vaccines for over ten years and Dr Lalwani was appointed as PI in many of them. It is one of the 14 hospitals where Phase II and phase III trials for Covishield were held on 140 volunteers. “The response was overwhelming in my hospital. I think volunteers came forward due to two reasons. One, many people thought that there is no way to get themselves treated other than being a part of the vaccine trial,” Dr Lalwani says. “At the same time there were volunteers who had this mindset that someone has to come forward for humanity,” he adds.

Trials for both vaccines have certain criteria to recruit volunteers, besides the fact they are supposed to be healthy adults. People who have contracted the virus cannot participate. So, an RT-PCR test along with an anti-body test are conducted on each volunteer before they are recruited for the trials. For instance, many volunteers were rejected as they had already developed antibodies; they had contracted the virus but remained asymptomatic. These people were themselves unaware about it until they underwent an anti-body test at the time of health check-up, a pre-condition for being recruited for the trials. “Out of 225 volunteers we had recruited, about 30 to 35 per cent couldn’t take part because of various reasons. Some tested Covid positive, some had developed anti-bodies, some left the trial midway after taking the first shot,” Dr Lalwani says.

Other hospitals also recorded a similar ratio of recruitment and rejection. Similarly, pregnant women, lactating mothers and those planning to conceive cannot volunteer. One of the inclusion criteria for volunteers of Bharat Biotech vaccine trial says that male volunteers who have reproductive potential have to use condoms “to ensure effective contraception with the female partner and to refrain from sperm donation from first vaccination until at least 3 months after the last vaccination”. Besides the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the law on clinical trial says that each participant should be informed about the vaccine, its side effects and adverse side-effects which can endanger their lives too.

“After explaining everything to them, we take their consent. Many of the volunteers left the hospitals saying that they would think over it but never came back,” another investigator says. “Many young unmarried women came forward for the trials and as an ethical practice, I told them that in an adverse case scenario, they might lose the ability to conceive. Some of them refused to be a part of the trial but there were many others who volunteered for the cause,” he adds. “There was a young lady who broke down after taking the first shot. She told me that she was taking it without her parent’s consent as she was emotionally dejected after seeing the plight of people during the pandemic,” he reveals.

Also, it takes courage to be a volunteer. “It takes a lot to remain committed to the cause of clinical trials after a healthy adult learns that the side effects can even lead to his or her death,” says an investigator at a Mumbai hospital. Doctors engaged in the recruitment of volunteers say many people participated out of their pain of losing close relatives or friends in the pandemic. “Some of them told me that they were emotionally disturbed over the death and plight of humans and wanted it to end. The vaccine was the only solution so they came forward.”

In many cases, healthcare workers, nurses and doctors working in Covid wards were preferred as volunteers. It serves two purposes. First, their participation was vital to assess the efficacy of the vaccine as they spent most of the time in Covid wards and are exposed to the virus. Secondly, they inspire confidence among others.

National pride

Doctors say the most unique feature of the COVID-19 vaccine trial was that the majority of volunteers are highly educated—engineers, doctors, teachers, techies and chartered accountants— and they were quite aware of what the trials are all about. However, when a volunteer for the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine trials died in Brazil and along with other drug-regulators, DCGI also put the trials on hold, it was a testing time for all the stakeholders. “Volunteers got suspicious and some of them dropped midway. We faced many health-related concerns of volunteers during that time,” Dr Lalwani says.

Another case of severe side-effect came from Chennai where a volunteer alleged that ten days after taking the first dose on October 1, he suffered from “acute neuro encephalopathy”, a brain disorder that left him disoriented and unable to do day-to-day work. His legal notice to the drug manufacturer and the regulator said he participated in the third phase of trials at the Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research because the death of millions of people all over the world had affected him emotionally. “Therefore, the public spirit in him wanted to help in whatever way he could in the effort to find a solution to end the current dismal situation because of COVID-19,” the notice said.

Though the Serum Institute of India dismissed the allegations that the volunteer’s condition was induced by the vaccine, doctors say it discouraged people to participate in other vaccine trials and led to shortage of volunteers. “Despite that, the Bharat Biotech’s trials got a huge response as people responded to the call of PM’s Atma Nirbhar Bharat,” says Dr Manish Kumar Jain, Department of Pulmonology, Maharaja Agrasen Superspecilaity Hospital, Jaipur. Jain is a principal investigator and his hospital is one of the 26 clinical trial centres in India.

“Our target was 1,000 volunteers but till date, we have registered over 1,350. Most of the volunteers participated as they appreciated that Covaxine was developed in India. They feel proud to take the shot of what they call ‘Bharat ka vaccine’,” Jain adds. Clinical trial laws in India say that a volunteer should be reimbursed for commuting from home to hospital and loss of daily wage due to participating in the trial, but doctors say that a majority of the volunteers didn’t ask for any compensation at the time of signing the consent from.

“The only demand they raised in my hospital was that if their shot turns out to be placebo (dummy shots), they and their relatives should be administered the vaccine on priority,” Dr Lalwani says, adding that in the SII vaccine trial one-third of the volunteers got placebo while the rest 2/3 received the vaccine. For vaccines, researchers compare what happens when a large group of volunteers gets the shots, versus what happens to another large group that doesn’t. For this, researchers randomly assign participants to receive a vaccine or a dummy shot, usually a dose of salt water.

Sanjay Kumar Rai, principal investigator, AIIMS, New Delhi, also says that he faced shortage of volunteers only till the time people were not aware of the vaccine trial. Rai said that initially, volunteers thought that his hospital was vaccinating everyone. “So, when they came to us we told them that in Covaxin trial, half of the volunteers would get placebo and half would get the vaccine. They refused to join the trial and left. But when we spread the word around about the shortage of volunteers, we got an encouraging response.”

The hospital is paying Rs 750 to each volunteer to cover their commuting cost per visit. “But no one is motivated by money. Their spirit of public service will outweigh everything,” Rai adds.

Like Vijay Sharma, 23, a college graduate from Indore, who wants to join the army and take a bullet for the country but is “happy with a vaccine shot now”. He travelled 600 km to a Jaipur hospital for the trials.

***

Clinical Test

2020 7,576

2019 5,769

2018 5,766

2017 3,435

2016 1,148

2015 1,130

2014 1,077

2013 993

2012 961

2011 742