... There were green

Tattoos on their cheeks, jasmines in their hair, some

Were dark and some were almost fair. Their voices

Were harsh, their songs melancholy; they sang of

Lovers dying and or children left unborn....

Some beat their drums; others beat their sorry breasts

And wailed, and writhed in vacant ecstasy.

—The Dance of the Eunuchs by Kamala Das

They say Musa Suhaag, a Sufi saint who wore bridal attire and joined a group of transgenders, danced until the skies crackled and rains poured down. In memory of the departed lies the faith that it will rain again in a distant city. That was in 2017. I was in the graveyard of Shahibaug: the dargah of Hazrat Musa Suhaag.

It is said that Musa encountered women in their bridal attire who said they were suhagans. He was on his way to visit the darbar of Mehboob-e-Ilahi or Nizamuddin Auliya. That’s when he wore a bridal attire with wrists full of bangles. In Ahmedabad, Musa joined a group of transgenders and lived with them. This was when a drought struck Ahmedabad. Musa danced and the rains came. He disappeared.

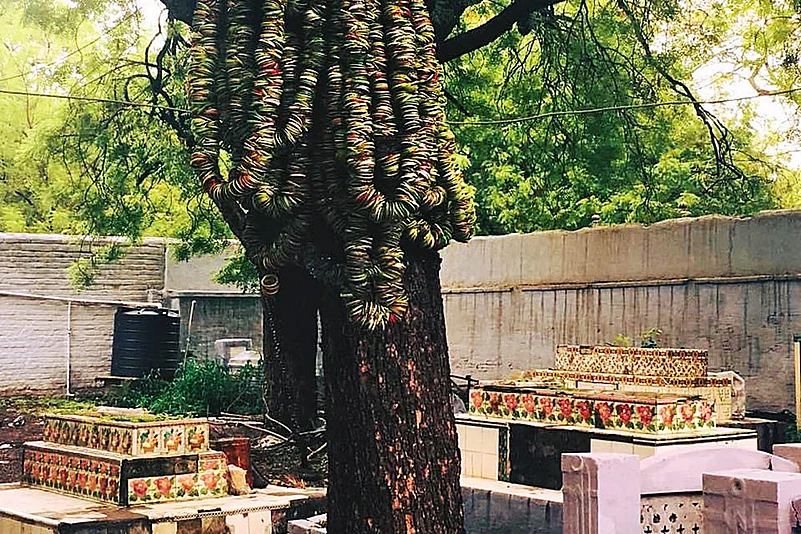

That afternoon, I saw thousands of green bangles strung together and wrapped around the trunks of the ancient trees by those who came to the shrine in Ahmedabad to pray for love, motherhood and rain. That afternoon it rained. In the graveyard that surrounded the shrine of the saint who was allowed the transgressions of gender, the rose petals scattered around the epitaphs looked solemn. A few women sat in a corner in silence.

“If you want a husband, a child and love, you pray here,” one said. This was the shrine of the “mad one” and they began to tell the story. I found no transgendered people there. Only the bangles and the echoes of a story. Many years have passed. Hijras can’t marry or adopt legally in this country. But they can bless others with love and fertility. The dichotomy between all this policy and all these stories is wretched.

***

“Once Gudiya tried to tell her that hijras had a special place of love and respect in Hindu mythology. She told Kulsoom Bi the story of how, when Lord Ram and his wife Sita, and his younger brother Laxman were banished for fourteen years from their kingdom, the citizenry followed them, vowing to go wherever their king went. When they reached the outskirts of Ayodhya where the forest began, Ram turned to his people and said, ‘I want all of you men and women to go home and wait for me until I return.’ Unable to disobey their king, they went home. Only the hijras waited faithfully for him at the edge of the forest for the fourteen years, because he had forgotten to mention them.

Bangles strung on a tree by the faithful at the shrine of Hazrat Musa Suhaag in Ahmedabad.

‘So we are remembered as the forgotten ones?’ Ustad Kulsoom Bi said. ‘Wah! Wah!’” (Ministry of Utmost Happiness by Arundhati Roy)

That graveyard in Ahmedabad could have been the place where Anjum, a hijra, lived with her adopted daughter Zainab. But this isn’t about the book. It is about the bits and pieces of mythology we find tucked away in books and in memory. This is about those stories. This is about the encounters with those from the hijra community. But sometimes, to get to the point, we have to come through a labyrinth of narratives. Sometimes, it isn’t about the point or the argument. Sometimes, it is just a recollection, a sense of wonderment, a feeling of betrayal.

Zeenath, a hijra guru from Mumbai, once told me this story about hijras and Lord Rama when we were in Ajmer together for the Urs of Khawaja Moinuddin Chisty in 2013. She told me the eunuchs had been blessed by Lord Ram. Zeenath had said if only they could have been blessed with a womb. Or if the gods had blessed the world with more love, things would be different. Zeenath had adopted a boy and a girl. Illegal, if one looks at the law. She also had eight other eunuchs to look after. She was a mother to them, too. She told me another story. She told me the Khwaja had blessed the eunuchs.

Once among the pilgrims, there was a woman struggling to lead her children to the top of the hill. A eunuch offered to carry her children. The woman told the hijra to stay away from the child. The hijra prayed at the shrine to become pregnant. The wish was granted. For 10 months, the hijra carried the child in her womb. With a bloated stomach, the pain was intense, unbearable. Prayers for redemption from this tyranny of desire weren’t granted. In the end the hijra cut open the stomach. A child’s face was revealed. Both died. A shrine was erected in their memory.

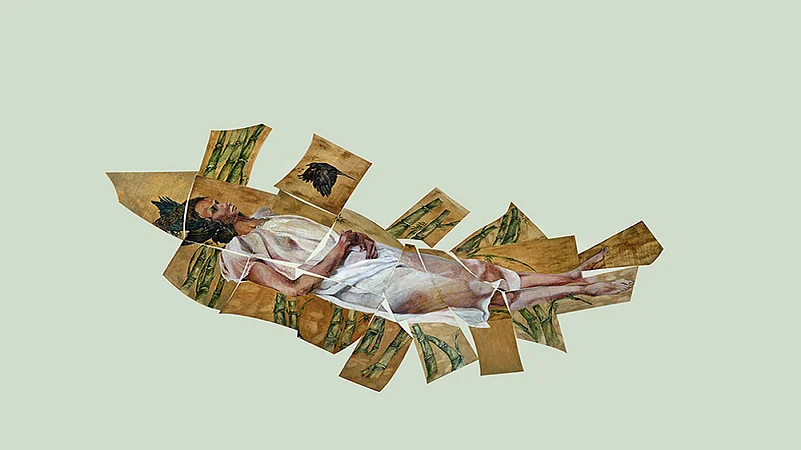

Photos from the author’s encounters with Zeenath, Gauri and other transgenders in Mumbai and Ajmer.

Hijre Ki Mazar, the twin shrines—of the hijra and the child—lie next to each other in Taragadh in Ajmer. They called the hijra Maji. She said they are forbidden to utter that name. Everyone goes to “mai” to ask for a child. In every such story, whether the bearings are rooted in fact or fiction, the need for reassurance is evident. There is the ambivalence of it, too. The wish and the impossibility of it are both manifest in the same story.

Today morning, I called a long-time friend and a transgender activist Aher Abhina. She said she had adopted a boy whose parents had died and his grandmother was a jogti. Abhina provided for the child and now, he is 22 years old and works at Air India. She said she cut off her ties slowly. “It is the stigma,” she said. “Transgenders can’t adopt legally. But motherhood doesn’t require gender.”

Abhina also is a guru to many young transgendered people who left their homes or were shunned. “We are still struggling for civil rights. The right to marry, to adopt,” Abhina said.

***

In 2012, I walked up the narrow staircase of Ramabai Chawl in Kamathipura in Mumbai. The air was heavy with the stale smell of cheap perfume, flowers, cigarettes. It mixed with the smell of cooking and of sweat. On the second floor, eight eunuchs lived and worked as prostitutes.

I remember the cheap blue tarpaulin sheets that covered the berths stacked in rows and columns where the eight eunuchs spent their nights whoring their bodies. I have told this story many times. Some stories need to be retold. Like those fables. Like those tragedies. Like those redemption tales.

Zeenath was dressed in a black chiffon sari with a silver border. She wore these chandelier earrings that almost touched her shoulders. Her wig reminded one of old-time heroines. The coiffure, the little adornments. She held a baby in her arms. A young girl sat next to her. Zeenath had adopted the girl from a young woman who had been suffering with HIV/AIDS and couldn’t afford to bring up a child. She worked as a prostitute in a brothel.

Zeenath had named the baby Saleha. “She will study, and she will get out of these streets,” she had told me then. She had also adopted a boy. He was seven then. His mother, a sex worker, had died of HIV/AIDS soon after he was born. He would leave the brothel at around 4.30 pm for the night school run by an NGO in the locality for the children of sex workers. He would return at around 8 am to a rearranged house.

ALSO READ: Adoption Is A Giant Monkey Puzzle

Zeenath would sweep the corridors and the staircase in the morning. She would remove the used condoms, the cigarette butts and the alcohol bottles. The same afternoon, I had met Gauri Sawant, a trans-woman, in Malvani in Mumbai. She was the director of Sakhi Char Chowghi Trust which worked with transgenders and HIV-positive members of the community.

She had adopted a girl child named Gayatri in 2008. Her mother, a sex worker who had green eyes and a fair complexion, died of HIV/AIDS. Gayatri was six at the time. “I became a mother by accident,” Gauri told me then. Five years later, “Touch of Care”, the advertisement from Vicks, based on the story that took us to Malvani to meet Gauri, went viral.

The ad follows Gayatri, as she makes her way to a boarding school on a bus. Gayatri talks about her adoptive mother Gauri and says she wants to become a lawyer so she can fight for her mother’s rights as a transwoman. “My mother wants me to become a doctor,” Gayatri says in the advertisement. Our story called ‘The Eunuch Mothers’ was first published in Open magazine in 2012.

Stories of hijras adopting children aren’t new. Mandwa, a young man who had run away from home and taken Gauri as his guru. That’s the other adoption story. Of bonds that are not sealed by blood. There is no umbilical cord. There is only trust. “The truth is, we will always be incomplete women. Not here, not there,” Gauri told me. But the non-blood family structures of the community weren’t recognised in the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill in 2019.

***

Zeenath Pasha, the guru, had been living in Ramabai Chawl for more than 25 years. She had run away from Hyderabad after she was disowned by her family for being a transgender person. She found Sushila Ma, her guru, in Mumbai. Zeenath had been born as Mehraj. When Sushila Ma died, Zeenath became the guru as willed.

Zeenath and Gauri are adoptive parents and hijra gurus.

The bill that was passed in the Lok Sabha categorically failed to recognise the traditional structure and non-blood relative families (hijra communities) support systems. “If the immediate family is unable to care for the transgender person, the person may be placed in a rehabilitation centre, on the orders of a competent court,” the bill said. It showed the disconnect between policymakers and the community.

ALSO READ: Adopting, The Light & The Black

Abhina ran a shelter home from her house for young people who identified themselves as transgenders. “The guru and chela system is also adoption,” she said. For transgendered people, loneliness is an issue. Ostracised by society and state, they have been fighting for civil rights for a long time. As per the discipleship lineage system, a hijra guru adopts a person and then they become part of the kinship and hijra gharanas become apprenticeship systems. The ‘gharana’ system is an institutionalised lifestyle. The issue is with the heteronormative idea of a family. A chosen family is also a family.

While trans-adoption in hijra families has always been the norm, cases of normative child adoptions are many. More than ever, there is a need to revisit and reconfigure notions of adoption and motherhood within and outside the gender–sex binary. Despite being recognised officially as third gender citizens by the Supreme Court in April 2014, marriage and adoption rights are yet to be decriminalised for various groups of third gender minorities.

There are many stories of hijra filial affection. Urvashi Butalia’s story about Mona and her adopted “female” daughter Ayesha that appeared in Granta in 2011 is one. Motherhood can’t be a gender norm for performing womanhood. It is a patriarchal and outdated notion. From the perspective of civil rights, adoption should be made legal for the third gender.

***

Saleha must have grown up now. Ramabai Chawl will soon be gone. Instead, a high-rise will come up. Like in many other parts of Kamathipura. But it will always be that place where I first met Zeenath who told me stories. Love runs stronger than blood. The green bangles wrapped around the trees are testimony to that. Of faith and of bonds, too. Perhaps these are stories that the forgotten ones remember. Lord Rama had forgotten to tell them to go home. They had waited for 14 years. Theirs is an exile, too. They love, too. Like us. Like you. And the colour of love is red. Like blood. And love is fluid. Like motherhood. A rebirth doesn’t require a womb.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Motherhood Doesn’t Require Gender")