“My wife and daughters cried, hid my car keys to stop me from going to the hospital for the vaccine trials.”

Santosh Krishna More, 50, CSR Consultant, Pune

Santosh Krishna More is among the first 10 Indians to get two doses for Phase II clinical trials of the Oxford University-AstraZeneca vaccine, Covishield. The 50-year-old CSR consultant got the first shot on August 26 in Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University Medical College and Hospital, Pune, and the second on September 29—almost a month apart. But he is unaware what the vials contained as it is not disclosed during clinical trials whether a vaccine or a placebo was administered. “They will after six months,” More says, adding that each volunteer has signed a contract with the Serum Institute of India, licensed to conduct the Covishield trials in the country.

It wasn’t easy for him to become a vaccine volunteer, especially given the resistance from his wife and two daughters, aged 17 and 19. “My wife cried and pleaded. If something happens to me, who will look after our two daughters?” he says, recalling how she hid the car keys when he got ready on the morning of August 26 to go to the hospital for the first shot. “I searched for the keys, thought I misplaced them and took the scooter key. When I was about to go, my daughter came out with the keys and wished me with tears in her eyes.” He too was in tears on the way to the hospital. “I was full of thoughts. What if I die? I told myself it is still not a small achievement if I become a Covid martyr.”

ALSO READ: They Took The Shot For You

The strength came from a tragedy in the family. More was moved when he learned that his 48-year-old maternal uncle died of COVID-19 in Mumbai. “I decided I will do something for society. I thought someone has to come forward for this cause,” says the man who had raised funds and donated to government hospitals, ambulance drivers and paramedics during the lockdown and after.

More, who runs marathons for leisure, drove back home comfortably after the first injection. “The doctors advised me rest for 24 hours, but I felt a little tired and rested for 48. Thereafter I ran 5 km and felt fine,” he says, still taking all precautions like wearing a mask, carrying a sanitiser bottle and social distancing. A month ago, he ran a 50-km ultra-marathon, finishing in five hours and five minutes.

“I believe my participation in the vaccine trials will build confidence among the common people.”

Prof Dr M.V. Padma Srivastava, 56, Director, NIMHANS

As head of neurology at AIIMS, Delhi, Dr M.V. Padma Srivastava, is the first volunteer in the premier medical institute to get the first dose on November 27 for Phase III clinical trials of Covaxin, the vaccine developed by the ICMR and Bharat Biotech. Between the first shot and the second on December 23, life has changed for the 56-year-old Padmashri awardee—like she is now director of the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS). The one constant, however, is her determination—that someone has to come forward to instill confidence in others. “Who could be better than a doctor or a person with a background in science? It will build trust among people for the vaccine,” says the professor whose family supported her wholeheartedly.

Dr Srivastava wasn’t aware of the safety or efficacy of the Phase II trials when she took the first shot. She didn’t know if it was the vaccine or a placebo, but didn’t fret. “We are racing against time. The sooner we get a vaccine, the better. People like us need to cooperate,” she says. She didn’t feel any discomfort after the two doses. She knows vaccines trigger certain side-effects, but are perfectly safe. “It is important to generate data from the trials. Without data, we cannot move ahead,” she says. Reports state that AIIMS is facing shortage of volunteers for the Covaxin trials. Dr Srivastava attributes the low turnout to absence of answers to several questions. “All predictions on COVID-19 have gone wrong. We are unable to address people’s concerns. We are still learning. We don’t know how long this inoculation will provide immunity. The answers lie in the data.”

ALSO READ: Tried And Tested

“My 11-year-old daughter was happy that I volunteered in a vaccine trial for humanity.”

Anil Hebbar Koni, 56, Entrepreneur, Mumbai

Anil Hebbar Koni saw the worst of the pandemic during the lockdown—the poor, jobless people in the slums of Mumbai. The 56-year-old distributed ration to those households, ran six soup kitchens, gave migrant labourers money to help them go to their hometowns and villages. “I lost a few friends and relatives to the coronavirus. One of them was close to me. That got me thinking, if we don’t get a vaccine, then people will keep dying,” says Koni, who sells medical simulators. The cloud cleared when a friend rang him up from Pune and told him about the vaccine clinical trials at Mumbai’s King Edward Memorial (KEM) Hospital. “He said the hospital was short of volunteers. I contacted KEM and went for a health check on October 6. I came to know that they were looking for 100 volunteers, but had only 55 then.”

On October 7, the hospital informed him that his first shot was scheduled the next day. “I took the second dose on November 6. I felt a little tired for three-four days. I was fine after the second jab,” says Koni, who didn’t let his family know what he was up to till the first shot. On October 9, he told his wife—dean, School of Development Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences—and all hell broke loose. “She was angry. But my 11-year-daughter encouraged me, saying I did a good thing.” Koni’s 84-year-old mother was happy too, though she has no clue what clinical trials mean. “She thought I got a vaccine. Whether vaccinated or not, I’m still taking all precautions. I care for my family and my old mom.” After the first dose, he spread the word around on his social network. “That clicked and the hospital got 100 volunteers in two days.”

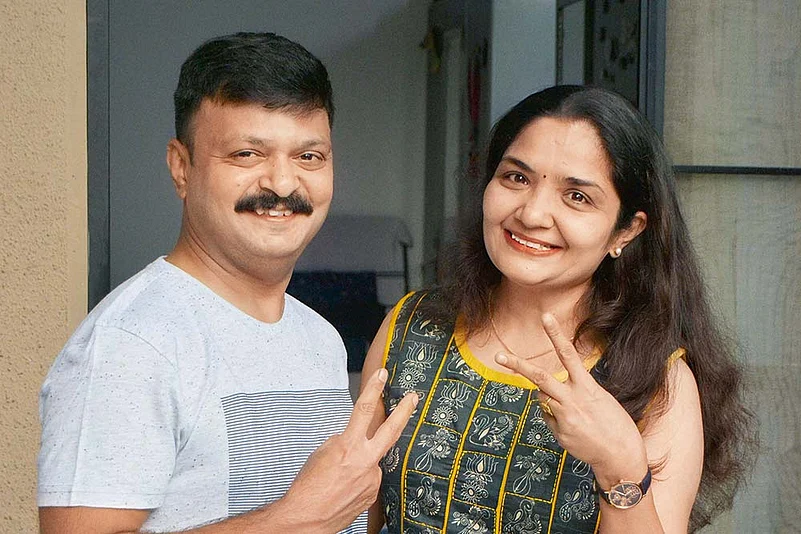

“My husband and I got vaccine doses, not a placebo, because we have antibodies now.”

Madhura Mandar Phatak, 42, Wellness expert, Pune

It was one hell of a blood test that gave so much joy to Madhura and her husband like no other before in their life. They have developed antibodies against the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19. How? Well, they volunteered for the Phase III clinical trials of Coveshield, the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, and got the first dose on October 30 and the second on November 28 at Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University Medical College and Hospital, Pune. “This (Covid antibody in their blood) proves we got the vaccine, not a placebo. We felt drowsy for two days after the shots. Took rest, slept well and did nothing. It was normal thereafter,” Madhura says. “There was no side-effect as such, though the doctor said we might get a fever, soreness or pain.”

“We got inspired by a neighbour, Shivanand Gokhle, who participated in the Phase II trials. He was fine,” Madhura says. It was her husband’s decision initially to become a volunteer. Madhura followed suit—“either both of us or none”. Married for more than 18 years, the couple worked out contingency plans for their teen daughter and son, who is nine, in case anything went wrong. They spoke to relatives, some of whom are doctors. “We learned that since the vaccine is made out of the virus itself, we might contract COVID-19 and have to quarantine. We will have to send our children to relatives,” she says.

Every move has a motive, and Mr and Mrs Phatak—wellness and nutrition experts in Pune—had one too. A prime driver behind their decision was to test the immunity levels of their bodies. “We take so much care choosing the right food, do regular exercise and maintain healthy habits…if the vaccine does not work on us, what will happen to people unmindful of their health?” In the end, it was a fun ride—a rollercoaster of psychological fluctuations. “When we look back at what we did, we feel good. What did we learn? Take anything with a positive mind and approach. It will bring a positive outcome,” Madhura says.

“I asked my parents thinking they might discourage me for the trials, but they rather accompanied me too.”

Pratibha Jain, 25, Marine electrical engineer, Jaipur

Pratibha Jain is a globetrotter—logging nautical miles on cargo ships as electrical engineer for the Maersk Line. The ship is her home and workstation for months—also a floating Petri dish for viruses because of the confined space. For a few months, she visits her parents in Jaipur. During a holiday in early December, Jain heard about the vaccine clinical trials in India. And the news about the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, which her Danish company has been contracted to ship around the globe. “I felt inspired to participate in the clinical trials of a Made in India vaccine,” Jain says. And so she walked into Maharaja Agrasen Superspeciality Hospital in Jaipur—where the ICMR-Bharat Biotech’s Covaxin is being tested on people.

That aside, Jain’s motivation was spurred by the hardship she witnessed during the lockdown. “So many seafarers were stuck in the sea, away from their families for months. A chartered flight flew me to a ship in June to replace someone who was there for more than 10 months.”

To her surprise, her parents supported her when she revealed her decision to volunteer for the trials. They wanted to join too. “We drove to the hospital about 18 km away and took the first dose on December 28. Since then, there is a good feeling that we are part of an exercise that will save humanity,” Jain says. She, her father Pradeep Kumar Jain, 55, and mother Mamta Jain, 53, were briefed about side-effects, but they haven’t had any.

“I had fever and body ache after each shots, but those were expected.”

Dr Karan Gupta, 41, Education counsellor, Mumbai

As an educationist, Dr Karan Gupta, a Harvard Business School alumnus, counsels students on careers and options for studying abroad. As a social activist, he teaches vocational skills to underprivileged women and children. Add another detail to his bio—a vaccine volunteer, after he took the Oxford-AstraZeneca’s Covishield as part of the clinical trials at Nair Hospital, Mumbai, on September 28. A month on, he got a booster dose. Gupta got into the act when news broke that a person ended up with a swollen spinal cord following vaccination in the UK. The flipside was that the number of Indian vaccine volunteers dropped soon after. “I realised that if we don’t have enough volunteers, we would never get a vaccine. And without a vaccine, we would never be able to stop this disease that has cost us so much. Therefore, without hesitation, I signed up.”

Wasn’t he afraid of side-effects? “Of course, I was. Taking a risk without fear is brave, but taking one with fear is braver,” he philosophises. His mother didn’t commend his “bravado”—and agreed reluctantly when he explained the pros and cons of the experimental vaccine. “She kept motivating me during the month-long trial period.” Gupta praises the hospital staff and officials associated with the tests. “They were extremely professional and cooperative”, and clarified every detail and query about side-effects, he says. He continued COVID-19 precautions even after taking the shot. “I wear masks, use sanitisers etc. The vaccine is not a magic cure and COVID-19 is not to be taken lightly.”

Gupta had fever and body ache after each of the two shots. “But I knew it was expected and could manage with paracetamol,” he says. On reports that fewer volunteers are turning up for the ICMR-Bharat Biotech vaccine trials, Gupta exhorts people to “discharge their duty as citizens of the world”. “This is a small sacrifice for the good of humanity. When 130 crore Indians are praying for you, what can possibly go wrong? Don’t be afraid. Your parents’ blessings are with you. I believe people will step in when the need arises.”

“My wife inspired me to get the shot.”

Dr R Kishore, 68, General physician, Faridabad

Dr Kishore shuttered his clinic in Faridabad—a first in more than 20 years, except for a few holidays—when the coronavirus infection spread and strict stay-at-home orders were issued last March. He sequestered indoors, considering his age, for months. But when the nation unlocked slowly, he opened his clinic: a brave move for a man in a vulnerable age group and who has to deal with the ailing, some might even be Covid carriers, for a living. “One has to face reality, with adequate safety norms,” he says. When he heard about the vaccine clinical test, he took it as an opportunity for him and his wife to get a safety cover. “She advised there is no harm in taking a chance since the vaccine for the masses is still a few months away. And so I went ahead…got vaccinated before others.” As a physician he was aware of the side-effects, but those are negligible.

His rationale sounds selfish, but his second intention deserves a salute—he became a volunteer to set an example for people hesitant to take part in the trials. “I see fear among people…they are scared to take the shot. There are misconceptions due to stray incidents of side-effects in India and abroad. Now that I have taken it, I believe it will convince many people to come forward.” He and his wife took the first shot on December 3, followed by the booster after 28 days at the ESIC Medical College and Hospital, Faridabad. Any side-effect? “Nah! The doctor told me I can get my blood tested to find out if I have developed antibodies for the virus. I will go for it to make sure I got the vaccine.”

“I wanted to join the army and get a gunshot for the country... I’m happy with a vaccine shot now.”

Vijay Sharma, 23, College graduate, Indore

Vijay Sharma landed a job with a private firm after his BCom(H) from Devi Ahilya Vishwavidyalaya, Indore, but lost it during the countrywide Covid lockdown. Jobless and staring at an uncertain future, he was shaken completely when he saw the plight of migrants last summer. It pricked his conscience and he vowed to help fight the virus plaguing the planet in whatever way possible. The opportunity came when he read the news that a hospital in Jaipur was short of volunteers for vaccine clinical trials. “I was disappointed. How come, in a country of 1.38 billion people, we don’t have a few thousand people coming forward for the trials? I decided I will do it.”

For a young man who wanted to enlist in the military but had to back off because of “family reasons” that he refused to divulge, patriotism and humanitarianism played out in equal parts when he decided to take a train to Jaipur, 600 km away, instead of the nearest clinical trial site in Bhopal, 200 km from hometown Indore. “If I cannot get a gunshot for the country, at least I can serve my motherland with a vaccine shot,” he says. He convinced his parents to come along. The trio set off on December 21 and reached Jaipur the next day. “About 11 am, I reached the hospital and got my health-check done,” Sharma says. “I didn’t know the Aadhaar card was mandatory to register for the trials. I had mine, but my parents forgot theirs.”

He got his first shot on December 22 and was told to come for the second after 28 days. Sharma was back in Jaipur with his parents—with their Aadhaar cards this time—and a cousin on December 26. They got their shots too. His mother had a swollen arm after the jab, and was advised painkillers and an ointment. “I was a little worried about her,” Sharma says. “The doctor said some people develop minor side-effects. We are travelling for the second dose on January 22.”

“A day after taking the first dose of the vaccine, I went for a 10-km marathon practice run.”

Shivanand S. Gokhale, 52, Businessman, Pune

A passionate marathoner, Shivanand S. Gokhale gives full attention to his and his family’s health and fitness. His family includes his bedridden mother, his wife and a daughter in college. His mom wasn’t happy when he told her his decision to volunteer for the vaccine clinical trials. “I was determined and told her that someone has to take the initiative. Why not us?” Opposition came from another front too—his daughter, “full of unfounded, preconceived notions against clinical trials”. Gokhale discussed the matter with her threadbare and once her mind got unclogged, “she was so impressed that she wanted to be a volunteer too”. But he decided that “we should go one at a time”.

His wife, with a background in biology, understood. She didn’t oppose, or encourage either. His two friends, who volunteered along with him, faced similar resistance at home, but got the go-ahead eventually. All three reached Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University Medical College and Hospital in Pune on August 27, and got their health and COVID-19 screening done. They were vaccinated the next day. “We didn’t feel anything. The next day, we went for a 10-km practice run for a marathon and one of my friends completed it seven minutes better than his best time. Was he administered some performance-enhancing drug? We joked,” Gokhale says. They took the next dose on September 28.

“The doctor warned that we would be dropped as volunteers if our Covid test reports came positive.”

Ranti Dev Gupta, 51, Businessman, Faridabad

For the amusement of all, WhatsApp posts are not that stupid after all. Ranti Dev Gupta, who runs three amusement water parks in Delhi-NCR, and wife Meenakshi Gupta, teacher at a government school, will vouch for that. Mrs Gupta learned about the Covaxin clinical trials on a WhatsApp group of colleagues. She discussed it with her husband and they decided to become volunteers “not because we wanted a vaccine, but to serve the nation”. They visited ESIC Medical College and Hospital, Faridabad, on December 3 and staff “gave us a booklet published by Bharat Biotech that had all the details about vaccination, side-effects, compensation et al”. “We read it and proceeded for a health check,” Meenakshi says.

First off, they underwent the RT-PCR test for COVID-19 and an antigen test to know if they were infected before. “The vaccinator warned us that if our two tests came positive, we would be dropped as volunteers,” Dev says. “The hospital kept us under observation for half-an-hour. The process was over in a couple of hours and we left for home.” The couple took the second dose on December 31. “I am in touch with two colleagues who volunteered for the trials. They haven’t developed any side-effects either,” Dev’s wife says.