Since Independence, the political participation of Indian Muslims has been a matter of debate, one that is getting more important by the day. After the 2014 General Elections, Muslim intellectuals are more actively discussing Muslims and their contribution to national politics. As India’s largest minority, Muslims are underprivileged and backward, and the reason for this is the evaporation of their political involvement. In the current scenario, political parties are treating Muslims as Shudra or untouchable, especially because there are no options available for Muslim voters. Their votes are for free, they don’t have a choice but the existential fear of BJP. And this has been misused by the so-called secular parties of India. But finally, during the last decade, Muslims have launched new political parties, showing that the community is now ready to demand its share in national politics. It’s also an outcome of incessant atrocities against the community.

However, the nature of these political parties is slightly different from those of the past. They are now appealing on the basis of secularism and trying to organise all oppressed communities under their banner. Since Independence, Muslims have faced invisible untouchability, which is now visible on all grounds. Discrimination in day-to-day life, pogroms, fake arrests and encounters, attacks on educational institutions, questioning of their minority status and character and fall in their share in politics, are a few highlighted reasons behind the need for a community-based political party. Now that Muslims are politically aware and putting a value on their vote, they are offering alliance on conditions, without which, they threaten to vote for their own party.

The rise of AIMIM and its president Asaduddin Owaisi, shows the community is feeling suffocated and demanding fresh air. Muslim issues on a large scale were never discussed at the political level, in order to bridge the gap between the community and existing political parties. But since the anti-CAA protests, the community began feeling the need for a political party. Instead of putting everything at stake to save “political secularism”, Muslim youth are now considering “political secularism” a monkey on their back.

A simple analysis of Indian politics shows that the share of Muslims in political life is falling, election after election, due to the blind faith they put in so-called secular parties. Not only was this breach of trust misused, it was also ultimately broken. Abdul Jaleel Faridi, a visionary, felt this abundantly long ago. Having seen post-Independence anti-Muslim riots happen under Congress rule, he strongly opposed the Grand Old Party and termed it as the biggest enemy of Muslims. Even though he was a strong opponent of Congress, he too joined the Majlis-e-Mushawrat (MeM) founded by Sayeed Mahmood, a man once projected by Congress to regain its popularity among Muslims. It was a non-political wing founded with a nine-point programme on Muslim issues. Even though he ultimately left it, he continued to encourage Muslims to join parties whose programme was more or less similar to that of MeM.

But even after Sanyukt Vidhayak Dal (SVD), formed through a merger of smaller parties, assumed power in UP, not much was done for the betterment of Muslims. Left with no choice, Faridi formed his own political party Muslim Majlis in 1968, whose aims and objectives were declared as: (1) to awaken political sense among the 85 per cent oppressed and backward people like Muslims, Harijans, etc. and enable them to face their oppressors and exploiters, (2) uniting Muslims, victimised by inferiority complex, under one banner to remove their sense of low self-esteem, (3) protecting and safeguarding the life, property, honour, culture, civilisation, language and religious beliefs of Muslims, (4) removing political, economic, social and educational backwardness of Muslims, (5) defeating communalism with the help of secular non-Muslims, (6) creating a society and atmosphere in the country to enable every citizen to lead a peaceful and respectable life, (7) fighting against unjust, unequal, biased and prejudicial government policy, to set up a secular system, and (8) protecting poor and weak people from exploitation by capitalists and oppressive rulers.

Faridi believed his programme of improving the lot of Muslims and other oppressed and backward communities could be better achieved by joining electoral politics and sharing power. In the same year his party was formed, he organised a conference in Lucknow that was attended by well-known Dalit leaders including Periyar. Though later, this movement evolved into grassroots politics of Dalit leaders like Kashi Ram, confusion remained. Faridi is a perfect example of leadership in post-Independence India, who gave confidence to the oppressed for demanding their political share. It’s the bad luck of the Muslim community that they failed to find anyone to carry forward his legacy.

But since 2014, and especially after the anti-CAA/NRC protest, the need for a political party of Muslims once again began to be felt. Faridi’s party was revived with Prof. Basir Ahmad Khan (ex-pro-VC of IGNOU) as national president and Imran Eijaz as Delhi state secretary. According to Eijaz, the root cause of Muslim backwardness is the lack of Muslim representation in Indian politics. He refers to politics as an umbrella without which the condition of Muslims can’t be improved at large and strongly advocates the need for a community-based party that will raise issues of Muslims with honesty. There is widespread concern about the poor quality of political leadership among Muslims. Even those who are honest, selfless and well-intentioned, are seen as too focused on short-term goals and struggles, and lacking in vision about how the practice of politics can strategically advance long-term welfare and status of Muslims. The older generation of Muslim leadership is seen as having been culturally divorced from the concern of ordinary Muslims, compromised as they were by their association with secular parties. But the energetic and educated youth do not want to compromise with their votes anymore. These bold educated voices, including the likes of Sharjeel Imam, managed to convince the masses that so-called secular parties are actually communal and Islamophobic to the core, and that the community must not rely on them.

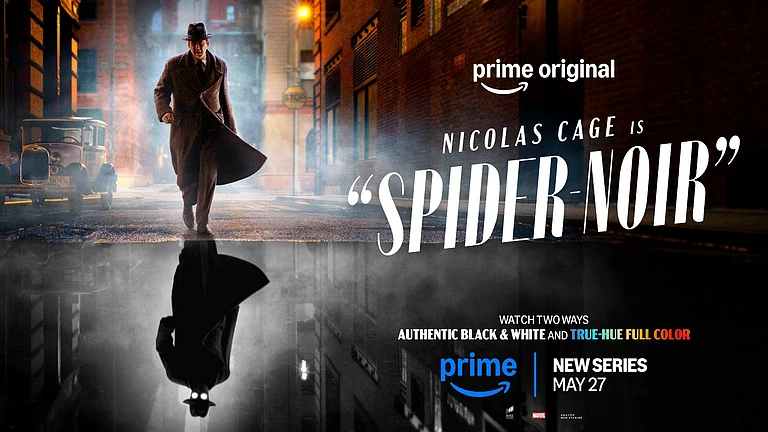

Aligarh Muslim University Politically active AMU alumni after a state-level meeting of Muslim intellectuals. Photograph: Faroagh ul-Islam

In Muslim Indians: Struggle for Inclusion, Amit Pandya writes: “The scattered Muslim votes are also responsible for their poor treatment by political parties. Muslim power is fragmented among multiple political parties, and its voice is fragmented by region and subcommunity. Even politically active Muslims are not in influential or leadership positions within secular parties, thus limiting the reach and depth of Muslim issues in secular politics.”

Politics is defined by a new uprising. Abhishek M. Chaudhari, in his paper: Rise of Muslim Political Parties, finds that Muslims have not prospered in any state run by a “secular” party, whether it is UP, Bihar or even Communist West Bengal. He observes that Muslims are now fed up with the treatment they have been receiving from secular parties and are willing to demand their political share. The politics of the last 30 years was defined by the creation of caste-based parties comprising various strands of OBCs and Dalits—which branched out from mainstream political parties in many states. The 21st century may see Muslim parties seeking to discover their own agency. Identity politics is a new uprising among minorities and the oppressed, who have come to the conclusion that only their own political party can give them the equality that secular parties have failed to accord. Political mobilisation can be seen among almost all castes and other prominent identities. Muslims are the only social group in India who are yet to discover their bargaining power. What is surprising is that Muslims took so long to realise that none of the parties really give them representation and share of power that their huge share of the national opulation—around 14 per cent—deserves.

Unlike in the past, Muslims are now gathering the confidence that was buried under the blemish of Partition for seven decades. They aren’t happy in the temporary shelters of secular parties, because secular parties do not consider them as partners or stakeholders, rather consider them as a burden. Educated Muslim youth have aspirations in the political domain and believe only identity politics can be used for uplift of their community. This educated group of politically active youth is pointing out the losses their community has faced by supporting secular parties, using the historical blunders to convince their community of the need for their own political party.

Among these youth, a very prominent name is Amir Mintoee of Aligarh Muslim University Coordination Committee (AMUCC), which he founded just after the police atrocities on students on the night of December 15, 2019, at AMU. Under the banner of AMUCC, Mintoee is trying to gather and convince Muslim elites across India to join identity politics. As a history student, he has a well-researched narrative on why Muslims must stop relying on secular parties. The new development among the Muslim community is that it is now talking about utilising its strength for community upliftment, rather than getting engaged in a ‘BJP harao’ campaign launched by secular parties.

The surge of regional political parties of Muslims reflects newfound confidence in the minority community in organising political parties with the community’s interest in mind (Abhishek M Chaudhari: Rise of Muslim Political Parties). Parties like Welfare Party of India (WPI), Social Democratic Party of India (SDPI), Peace Party (PP), Rashtriya Ulema Council (RUC), All India United Democratic Front (AUDF), and All India Majlis Ittehad ul Muslimeen (AIMIM), are proving themselves to be important players at the regional level, with AIMIM already getting a good response from the community at the national level. With these parties on the ground, national politics is about to take a turn where a new politics, where a Hindu party aligns with Muslim and Dalit parties, might happen. Muslims are claiming their political share, the credit for which goes to secular parties for ignoring the largest minority and fully losing their trust. Potentially, this can not only change the political status of Muslims and other oppressed classes in India, but also the national political scenario.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Return of the Repressed")

(Views expressed are personal)

Faroagh ul-Islam is a freelance writer and poet