At the end of May, I undertook a joyride in the districts of Amritsar, Ferozepur, Muktsar, Faridkot and Tarn Taran, on both sides of the Sutlej. It was a chance to see and learn—a rare thing these days. The hot, dry summer had set in; the wheat had been harvested, the straw was being piled into big heaps and plastered over with mud—a makeshift igloo. Cattlefeed for the year. There was a vibrancy—as only in Punjab—even in the mid-day sun. It also happened to be a Sunday. We drove through Tarn Taran, past my village, and on to Harike, the great Bhakra barrage, at the confluence of the Beas and the Sutlej. This drive through the heart of Punjab had been some time coming and I was hungry for visual satiation. My companions, Tarn Taran-Goindwal farmers, added spice.

I found clutches of happy Sikhs by the roadside, eager to offer sustenance to passersby. A roadside shamiana had something cooking and young men were hailing down and urging people to partake. I asked, “Is it a special Guru purab?”—the Sikh calendar affords plenty of opportunity to celebrate all year around. “No,” they said, “this happens every Sunday.” Why? It’s a tradition in Tarn Taran. Villagers, feeling generous after the harvest, cook a meal for people by the roadside. Those who are fed are welcome to leave a contribution if they should so feel, but no one is explicitly asked.

In the small towns, I found the roads dotted with ‘marriage palaces’ with romantic-sounding names from the UK—a hangover of the Raj—just as the building industry around Delhi does: Marble Arch, Kensington, Oxford and God knows what else. Among Punjabi names, the favourites are ‘Eat Well’, ‘Naatch Le Palaces’. We do both with vengeance.

Farmers shell out around Rs 50 lakh to build these palaces. Fully furnished, they’re hired out for marriages at Rs 25,000-75,000 a night. Stocked with pots and pans, one need only bring the cooks and stores, have a quick bhangra-fuelled ceremony and clear out for the next lot. The happy farmer is an extra guest with plenty to eat and drink and nothing to do. Farmers with five-acre holdings spend up to Rs 6 lakh on a wedding, those owning 10 acres spend Rs 10 lakh, others may spend Rs 15 lakh (or more). Farmers with small holdings struggle with expenses. No wonder the sex ratio is so skewed.

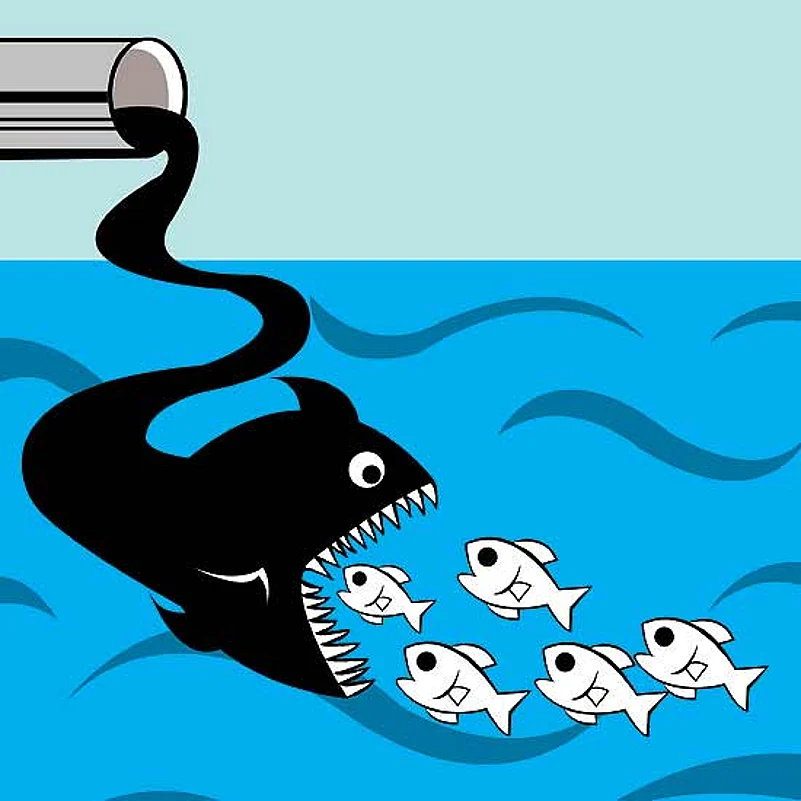

I crossed the Harike barrage and observed the coupling of the Beas, from Kangra and Kullu, with the Sutlej, from Tibet, past Ludhiana. My companions recount a horrifying anecdote. They had gone out on Harike lake with a forestry officer who told them that the fish in the Beas are fine, but those from the Sutlej have been blinded by the pollutants flowing out of Ludhiana. The idea of floundering, blind fish shook me. The poisoning of the Sutlej is spreading cancer across southern Punjab and, via the Rajasthan canal, into Rajasthan. The industrial belt from Ludhiana to Jalandhar is pouring waste into the pristine rivers that give Punjab its name. Guru Nanak’s Bein is sullied by Jalandhar’s filth. Baba Seechewal, an eco-activist of renown, is leading a people’s morcha to block these drains and force a sluggish administration to take action. They are in for a long fight with the industrial lobby.

Crossing the barrage, I was bemused to find a potholed road. While the superb highways were built by the NHAI, an indifferent Bhakra Management Board was in charge of the one-kilometre-long barrage. It seems this neglect is meted out to all the barrages in Punjab because the overriding interest is the water!

In Faridkot and Ferozepur, I travelled along the great Rajasthan canal, a ‘river of sweet water’, Punjab’s gift to that state. In the ’70s and ’80s, the canal had perfect brick lining and smooth embankment roads. Now, the brick lining has bushes and small trees breaking into it. No wonder I often read of canal bank ruptures affecting Punjab farmers. Times, I suppose, have changed.

Innovation is inbuilt in the Punjabi make-up. In the town of Talwandi Bhai Ke, I found a whole bazaar of agriculture machinery: trolleys, tractor ploughs, tillers, rice planters and land levellers. How come? The town is full of local manufacturers who make them just as good as big companies, at a fraction of the cost. They copy the Chinese rice planters, hundreds of which were brought in by the government. This helps address the labour shortage in the countryside. China should not be surprised if we start exporting planters to them! The intensive vegetable farming in greenhouses here is the handiwork of Muslim vegetable growers from UP, leasing land at attractive rates and, with their diligence, still making a profit. There are private schools and colleges everywhere. Excellent buildings, which I think will ultimately impart quality education, with competition weeding out the inefficient ones. These institutions, again, are invariably called Oxford, Cambridge or Oxbridge. Sadly for the Americans, no one in these parts has heard of Harvard and Stanford.

(The writer is the Union minister for youth affairs and sports. He was formerly Punjab’s agriculture secretary.)