Pilibhit, Uttar Pradesh: For Pankaj, it was love at first sight. He saw Nidhi from his office window, and then waited to see her every day, as she crossed his office to and fro from college. His cousin, a classmate of Nidhi’s at the all-girls’ college, helped him deliver notes, flowers and chocolates to her and eventually Pankaj convinced Nidhi to meet him at a temple where he proposed friendship to her. Nidhi accepted, and over the next few months they fell in love—mostly on the cellphone. Pankaj and Nidhi are from different castes—Pankaj from the ‘lower’ Kurmi caste and Nidhi from the high Rajput caste. They could not be seen together—even though this was a town, their families would have come to war over it, and the young lovers would have borne the brunt of it. Aware of the dangers, they immersed themselves in a parallel universe, chatting for long hours on their mobile phones, thanks to cheap calling plans. Eventually their love was exposed via a text message that Nidhi’s brother found on her cellphone. He threatened to kill Pankaj, so Pankaj and Nidhi planned their escape (also on the cellphone), eloped and took refuge at Love Commandos, an organisation in Delhi which helps runaway couples in love by arranging speedy marriage ceremonies and offering them protection from their families and communities.

Pankaj and Nidhi’s story is not uncommon. At the headquarters of Love Commandos, I meet many couples like them—couples who fell in love across caste and community lines, their relationships mostly conducted via conversations and messaging on their cellphones, for they’d be unable to meet because of strict restrictions imposed on girls by their families. According to Sanjoy Sachdev, founder of Love Commandos, “If it wasn’t for mobiles, most of these couples wouldn’t have found love. For them, the cellphone is a gift given by god himself.” He says that it is because of this very fear of young people falling in love that several khap panchayats have advocated banning cellphones for women.

When I ask 21-year old Nidhi what she would have done if she didn’t have a cellphone, she looks at me blankly and doesn’t have an immediate answer. Finally, she says with some hesitation, “Letters. We could have written love letters to each other.” But Nidhi has never written a letter to anyone in her life.

India’s Sexual Revolution

As I write in my book, India is going through a sexual revolution. The country is entering uncharted territory and most notions related to love and marriage which were pertinent to your parents and their ancestors are changing in the modern age. Arranged marriages are shattering, divorce rates soaring and new values and paradigms related to love, sexuality and marriage are feverishly in the making. The cellphone has been one of the biggest aids to the sexual revolution as one generation struggles to free itself from the boundaries—physical, mental and emotional—set up by the previous one. Cellphones and all of the accompanying paraphernalia, including messaging, and even dating and mating applications, have made it easier than ever before for Indians to connect and conduct relationships on the phone.

As I travelled across the country, interviewing close to 400 people in 15 cities, big and small, for my book, it was foregrounded by one crucial fact: India is the third largest smartphone market by sales, after China and the United States, and since the end of last year, it has been the fastest growing. Messaging apps like Whatsapp, BBM and Hike have become crucial to building relationships, especially for young Indians. Some products are tailored specifically for the Indian market. For example Hike, a messaging service, just surpassed 20 million users since its inception two years ago, and is popular in the under-25 age group. It offers features such as concealing the last-seen timer which help young Indians cloak aspects of their social lives from their parents—hugely important in a country where there is an extreme generational divide.

To find out more, I speak with Pallavi, a 20-year-old student at Delhi University from Lucknow. According to her, it is not practical to be in a relationship without a smartphone. “I can’t imagine being in a relationship without Whatsapp or Snapchat,” she says. “That is why it is so important to have a good phone. Most of my friends save up good money to buy nice phones.” Pallavi has recently broken up with her boyfriend of three months. The reason: he didn’t have a smartphone. “I felt disconnected from him all the time. It was impossible to be his girlfriend without Whatsapp.”

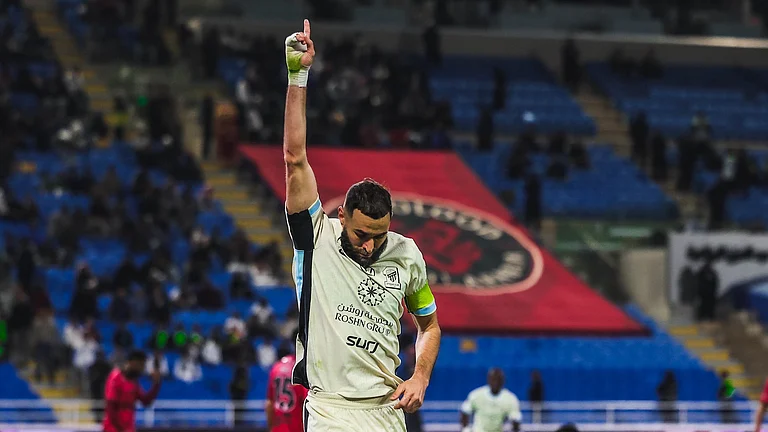

Selfie-interest A couple on the Gateway of India in Mumbai. (Photograph by AFP, From Outlook 3 November 2014)

Mobile phones have become crucial not just to maintaining relationships but also in starting them. Dating applications like Tinder, Thrill, Woo, DesiCrush and Truly Madly are flooding the Indian market, as it opens an entry-way for young people into a virgin dating scene. According to Tinder’s vice-president of communication Rosette Pambakian, its user base in India is growing by over 1 per cent per day. Anita Singh, a 32-year old professional living in Bangalore, says Tinder has changed the way she met and dated men. “Earlier, I was reliant on my family or friends to introduce me to men. It’s not possible in India to go to a restaurant or bar and meet someone. Tinder has changed the way I date. I go on at least two dates a week, and have found lots of nice singles on Tinder.”

For many, it’s more than just dating. A virtual world where your identity is concealed allows young Indians to explore their sexuality in more ways than one. Applications like Planet Romeo have heralded India’s gay revolution and has allowed India’s gays to cruise freely and engage in no-strings-attached sexual affairs. But it’s not just amongst India’s homosexual community that these applications are popular. Farhan, a 27-year-old from Delhi, regularly gets “lucky” on Tinder. Since he started using it three months ago, he has had one-night stands with three women in Delhi. All three times, he went over to the woman’s house within 30 minutes of contacting them, or “swiping right” in Tinder terminology, and left after a sexual liaison, never to see them again. According to Farhan, all three women were in their early 30s—who lived with their partners (he is unsure of whether they were husbands or boyfriends) in Delhi and were interested in sexual discovery. They all liked Farhan’s profile—he was young, nice-looking, educated in an elite foreign university, and ran his own business. so thought he was “safe” and called him over. While Farhan has a profile which is attractive to young women, there are others who resort to the age-old model of sex-for-sale. But even in that industry, the cellphone has created waves of change.

Sex work and the Cellphone

In New Delhi, I met Nita, an attractive and fashionable 25-year-old from Shillong who works as a waitress in an upscale restaurant in the day, and as a sex worker at night. Neha carries three cellphones—a sleek Samsung, which is her personal number, while the other two, a basic Blackberry and a touchscreen Nokia, constitute her “work phones”. Neha tells me that the cellphone has revolutionised the sex trade industry and made it much easier for her to access clients—and for clients to access her.

What Nita says is bolstered by statistics. In a 2006 survey, 58 per cent of Delhi men (urban, middle-class) surveyed said that they had solicited sex workers. Another 2011 survey had 54 per cent of Delhiites in the same class segment saying they had lost count of the number of times they had paid for sex. Prostitution is just as widespread in other metros in India. According to police officials, things are going out of control in cities like Bangalore and Pune, where 54 per cent of male residents have said that they have had sex with prostitutes. The takers for this ‘new’ kind of prostitution are men, typically middle-class and above, who are comfortable paying between Rs Rs 5,000-10,000’ for young, attractive and well-groomed prostitutes, girls like Nita, who have come to the city to find their fortunes. According to Nita, who has been in the business for seven years now, she rarely needs to meet the pimps who organise her meetings—the entire business is conducted on the phone. “Earlier, men had to go to brothels. These are public places and many people are shy or afraid. Now, men just call up the pimps, who call us up, and it is all very easy. For men now, sex is just a phone call away.”

As I researched India’s new “middle-class” sex trade, I discovered that it was indeed the cellphone that had helped create and propel this new industry. This is also the reason why brothels such as Delhi’s GB Road and Bombay’s Kamathipura are dying slow deaths and losing customers to independent sex workers who operate on their cellphones and use hotels for their businesses, rather than the age-old walk-in business model of the downmarket brothels.

You don’t need to be rich to be my girl The mobile is a democratic device. (Photograph by AFP, From Outlook 3 November 2014)

The Cheating Cellphone

While it is apparent that the cellphone has exponentially increased connections of the heart and the groin, there is also a flip side. While relationships can be built on the phone, they can be destroyed on them as well. A recent 2014 Pew study found that a quarter of adults with cellphones who are in serious relationships report that “the phone distracts their spouse or partner when they are alone together”. Thirty-one per cent of parents reported that their partner was distracted by their cellphone in their presence, the study found. These numbers are even higher for younger adults. Forty-two per cent of 18- to 29-year-olds surveyed felt that a cellphone distracted their partner when they were together. Twenty-nine of those aged 30 to 49 years, said they felt that way. Though we are certainly building more and faster connections, they may also be of lower quality than ever before. And while cellphones have helped couples in love, they have also helped individuals who cheat. It is easier than ever before to conduct illegitimate relationships, but also easier than ever before to discover infidelity.

According to psychologist and relationship counsellor Vijay Nagaswami, “Almost 80 per cent of affairs today are discovered by stray SMSes and chat transcripts. Another downside of mobile phones is that young couples seem to prefer them as communication tools instead of good old face-to-face conversations. Although it may seem hard to have a fight through SMSes and Whatsapp, many couples seem to do this.” As India falls in digital love in droves, we must realise that cellphones have also challenged our relationships and made us realise more than ever before how volatile love and relationships are in 2014—and these can die as suddenly, and as frustratingly as the battery of a smartphone.

(Ira Trivedi is the author of India in Love: Marriage and Sexuality in the 21st Century.)