In a society that leads by example, you rarely come across dissenting voices. More often than not, such voices are hardly heard, much less appreciated. But the merit of precisely such non-conformity cannot be discounted. In a constitutional democracy like India, which has provisions accommodating diversity and plurality, it is often the opposite view that holds up truth amidst doctored and influenced opinions that seeks to be more politically correct.

In the illustrious history of the judiciary, whenever there has been dissent, the minority has held a small but powerful voice. The minority opinion, by giving a contrasting view, has laid the ground for potential criticism and stood up for the cause of justice when the majority has decided to toe the line against the public good.

The ADM Jabalpur v. Shivakant Shukla case, also known as the Habeas Corpus case, is a classic example of the minority voicing the truth only to be drowned out by the majority opinion. With the Emergency in place in 1975-1977, several people from the Opposition, or those who opposed government policies, were arrested and detained under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act, 1971, which had scarce regard for civil liberties of individuals. Fundamental rights anyway were suspended. The right to move courts for enforcement of any right too was suspended because of an order promulgated by the President. People who were arrested filed the habeas corpus petition in the high courts under Article 226 of the Constitution. These writ petitions contended that the arrests were not in compliance with the law under which they were arrested, or were mala fide in nature, or were cases of mistaken identity. Huge confusion prevailed among the high courts as well. Some sided with the petitioners, upholding their right to move the court for this, while others held that the right to move court had been suspended by the previous order.

When the case came before the Supreme Court, the issue at hand was whether right to life and liberty were protected only under Article 21 of the Constitution. The Supreme Court, abdicating its role as the protector of the citizens of the country, held that right to life and liberty were enshrined only in Article 21, and that there was no natural right to life and liberty, or to approach the court in case of its violation.

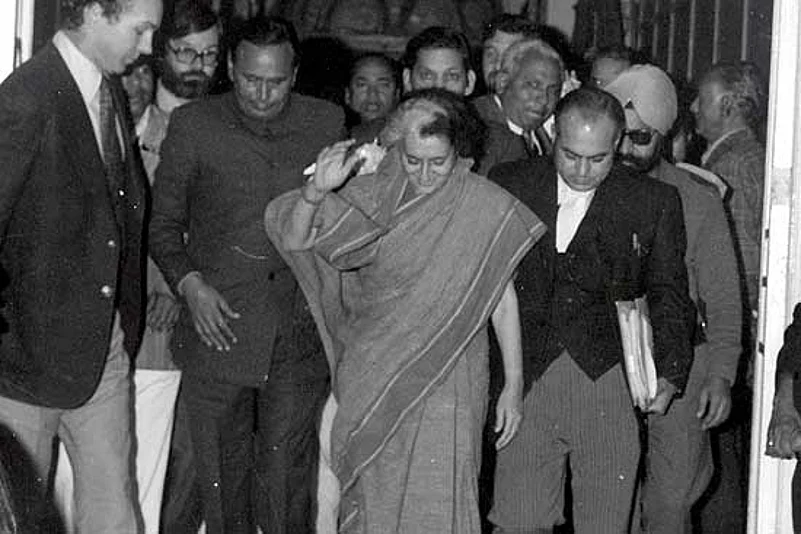

As against the four judges in the majority, one who was already the chief justice and the other three who all went on to become chief justices, Justice H.R. Khanna was the only one who gave a dissenting opinion in the case, daring to go against Indira Gandhi and her government, and upholding the right to life and liberty had always existed with humans, and that Article 21 was to ensure that the procedure in laws, which proposed to take away either life or liberty, did not violate the fundamental rights. Justice P.N. Bhagwati and Justice Y.V. Chandrachud both regretted having been with the majority then, and in later years gave dissenting opinions in cases like Minerva Mills, Bachan Singh and Olga Tellis, upholding the same right to life and liberty.

Other cases too have strengthened the premise that dissenting opinions are needed in a democracy that is so varied that they in itself are a form of check on the power of the judiciary. For example, in AK Gopalan v State of Madras, 1950, while the majority held that law was what was laid down by the state, and law under Article 21 of the Constitution did not embody the concept of natural law, it was Justice Fazal in the minority who said that law was always supposed to include the principles of elementary justice, and that any procedure established by law must include notice, an opportunity to be heard, an impartial tribunal and an orderly course of proceedings. Very often, we must be told what we don’t want to hear, shown the mirror time and again to ensure that our feet stay rooted. You need an anti-majority to keep the majority in check!