In thinking of the conundrum of English-in-India, it is important to get past two “nationalist” misconceptions, and perhaps August 15 is an appropriate date therefore: the first rests on the assertion that English is irredeemably foreign and contaminated because it was the language of the vile Brits, and it doesn’t behove a proud and independent nation to have anything to do with it. This is nonsense—English has been here and become ours over long centuries. The other, and opposite, misconception derives from the macho nationalism of the globalising Indian, misled by the great success of outsourced drudgery (think BPOs) into thinking that the minimal English that demands, liberally interspersed with lazy localisms (‘we are like this only’), somehow makes them—us—equal participants in the global banquet, as well as equal inheritors of English’s proud past.

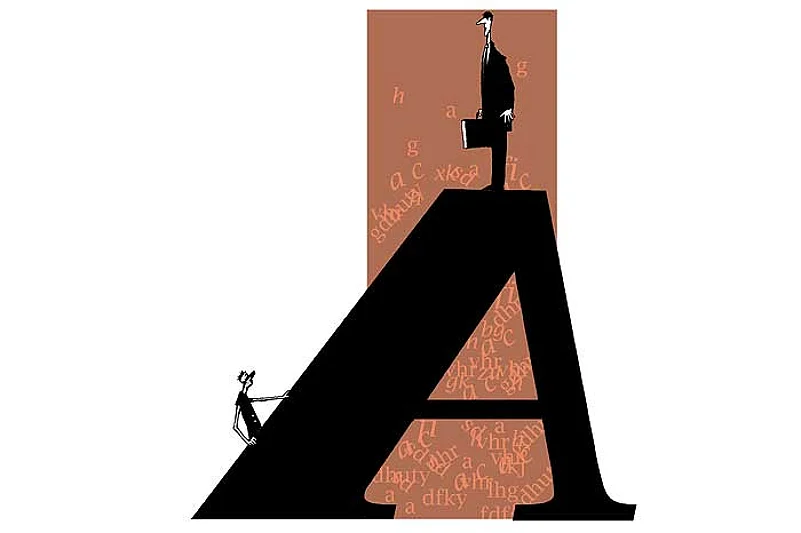

The key word here is equality: both nationally and internationally, English seems to hold out the promise of equality, of mobility, Friedman’s flat world—while in fact it serves to camouflage, consolidate and reinforce deep, systemic inequality. Of course, there is much more to this inequality—global as well as national—than merely English. If, by some miracle, everyone in the world were to acquire fluency in English tomorrow we would not awake into utopia. Day would still break upon the world we know, one of war, and weariness, and woe. Worse, we would not even be able to blame it on misunderstanding! The Globish-English hyped by Robert McCrum, and brayed incessantly on the TV channels of the semi-literate, is—after Orwell—merely the Newspeak of this brave new world, the bare and brainless dialect in which the stark inequalities of this world cannot even be called to mind, let alone be talked about.

India, then. Two of the most visible routes to mobility and success in our wonderful land are, of course, English and crime—perhaps in reverse order, because crime involves less investment. But of course if someone can combine the two (English and crime!) then they have access right to the top: the higher judiciary, the civil service—you want names?—and, why not, politics too. Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that the timid majority still prefers English. However, the likely social outcomes of this process are similar to what happens when hungry individuals run a red light, or break a queue. The collective as a whole—traffic-jammed, jostled, frustrated—is worse off, even if a few individuals do get ahead.

Under these circumstances, any attempt to restrict or even interrogate the epidemic longing for English rightly appears as an attempt to preserve the privilege of the relatively Anglophone. But by the same token, it is absurd to say—although people who should know better do say it—that somehow English can escape its Indian destiny as a language of privilege, and that English can become the lingua franca of the whole country, so that everybody can participate equally in the democratic life of the country because your flawless Oxbridge accent counts for no more than my stumbling, broken syntax. Further, English also bestows international mobility on everybody: the economic strategy of export-led growth extended to the very population of India as a whole!

This is an absurd and, yes, cruel fantasy; it truly doesn’t behove a proud and independent and half-way intelligent country to entertain or encourage such delusions. It is often said that the trouble with Indian writing in English is that English is not an Indian language. Actually, the problem is exactly the opposite—English is an Indian language. It is here, endowed with a legacy, associations with class and privilege that one might well wish were different. There is a powerful class of people for whom it is virtually a first language—indeed, their only language. There are many others for whom it will always remain entirely foreign. The cruel, damaging sense of inferiority that is inflicted on the non-English knowing is only half the tragedy implicit in this configuration. The worst of it is the wholly undeserved sense of superiority, the insensitive arrogance which characterises that highly visible section of the elite, whose sole intellectual and cultural asset is the ability to gabble away in a kind of semi-literate, fluently moronic English.

(Alok Rai is a professor of English at Delhi University)