George Orwell celebrated patriotism and decried nationalism. Ramachandra Guha celebrates both. Orwell of 1945 shared Guha’s mistrust of the Left, and both share a mastery of lucid, persuasive, prose. But, reading Guha’s essay Patriotism Vs Jingoism (Outlook, February 5), I was also reminded of Orwell, when he wrote, “A nationalist is one who thinks solely, or mainly, in terms of competitive prestige.” Guha’s dismay at our current state of affairs is understandable. This is the moment to celebrate, as he does, the history of a more inclusive, diverse and tolerant sense of belonging over chest-thumping jingoism. Even an ardent admirer of his writing, however, would question whether his was the best way to make that point. The argument he makes is necessary, even crucial, at this point in our history. But doing so by celebrating the superiority of Indian nationalism over other nationalisms robs his argument of its moral authority and historical gravitas.

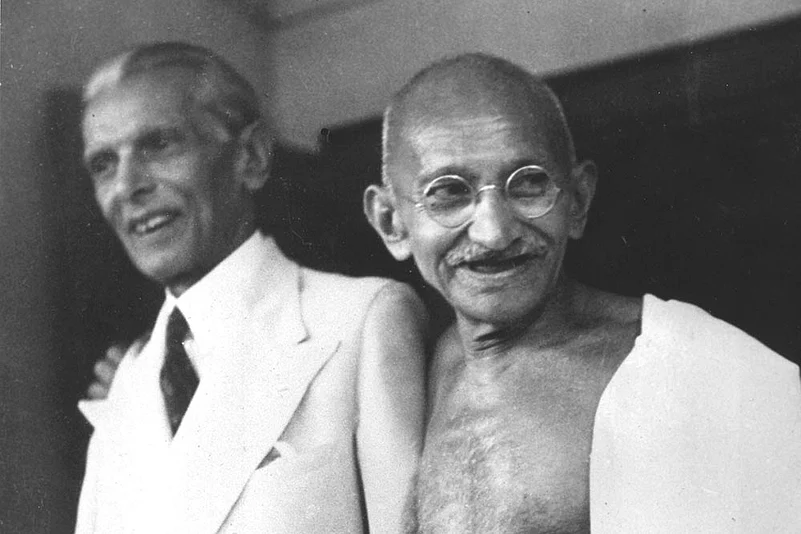

Elevating, as Guha does, Gandhi’s patriotism as superior to Jinnah’s nationalism (or Indian nationalism over its European variant) smacks of a competitive “my nationalism is better than yours” attitude, and undermines the point (however contestable) about distinguishing between patriotism and nationalism. Not only does it veer dangerously close to the jingoism that Guha rightly condemns, it compels him to marshal an argument open to historical questioning. To argue for a more inclusive nationalism doesn’t need an ahistorical celebration of “our” nationalism. Unfortunately, Guha appears to slip into precisely that competitive mode at many points in his essay. Surely, there is a better way to celebrate inclusivity and diversity than pointing out that we are better than the rest. Moreover, collectively, historically—in terms of the violence, injustice and inequities “we” (India or Indians) have heaped upon the less powerful among us—are we really better than anyone else? Not really.

It was surprising to see the ease with which Guha slips from Gandhian nationalism to “constitutional patriotism”, when it is quite evident in his magisterial India After Gandhi that the Indian State, which came into being, was not the state Gandhi envisioned, nor was the Constitution a Gandhian one. Gandhi was remarkably underwhelmed by parliamentary or other representative democracy, and makes that quite clear in Hind Swaraj. In any case, Gandhi’s vision was somewhat unique (even idiosyncratic) within his own party. Certainly, there is no way we can move from Gandhi’s vision of the nation to “constitutional patriotism” without acknowledging the huge differences between his and the very different visions of the nation within the party. The Constitution we have reflects debates and compromises between all these visions, and Guha knows that.

To prove his point about Indian nationalism’s moral superiority, Guha gives the example of Jinnah imposing Urdu on East Pakistan’s Bangla speakers. Does he find no parallels with the great constitutionalist Jawaharlal Nehru’s frankly colonial attitudes to the Nagas and the Northeast in general? How about his dismissal of the world’s first elected Communist government? Guha contrasts India’s “disaggregated patriotism” with Spain’s more unitary model to account for Catalonian separatism, but doesn’t ask whether the Indian government would permit a referendum on Kashmir—which is unlikely, given that students were arrested on sedition charges merely on calling for ‘azadi’?

Let’s certainly celebrate local patriotisms, as Guha suggests, but of Kashmir as much as of Karnataka, of Badgam as well as Basavangudi. A truly disaggregated patriotism would not insist upon the primacy of the national identity. The absence of Kashmir in this essay, just like Sherlock Holmes’s dog that didn’t bark, is quite telling. Could the absence be because the positions of the constitutional patriot and the jingoist on the Kashmir issue might overlap, with only different words being used? Moreover, isn’t mentioning Catalonia but forgetting Kashmir an example of not paying enough attention to people within the borders of the nation-state? He does level this important accusation against the Indian Left.

Guha has been sniping at the Left, sometimes for good reason, through much of his intellectual career. While welcome to the old chestnut about the failure of Communists to participate in the Quit India movement, it hardly behooves a scholar of his stature to make the anachronistic argument that students celebrating Hugo Chavez’s visit to JNU are somehow enabling jingoistic Hindu nationalism. Historians know that each nationalism, though representing itself as unique, is also a response to global contexts. Some Indian nationalists celebrated Britain’s enemies during World War II. Students celebrating Chavez, or those earlier supporting Saddam Hussein, rejoiced because these men were cocking a snook at the most aggressive imperial power of the day, the United States. They were not celebrating these leaders’ domestic policies, just as Bose was not endorsing the genocide by Nazis or Japanese war crimes.

By celebrating Chavez, the students were exhibiting their nationalism rather than mindlessly admiring a foreign leader. One may fault them for their understanding, but can hardly accuse them of enabling jingoism.

More seriously, to claim that the Left’s non-patriotism is the primary cause for the rise of intolerant jingoism in India defies all logic and history. It ignores the history of colonialism, which created modern religious identities and communal representation, and fails to acknowledge the primacy of many varieties of Hindu nationalism, from Bankim and Tilak to Savarkar and the Hindu Mahasabha, which have made our times possible. It forgets the extent to which global capital and associated technologies are complicit in enabling our current version of jingoistic nationalism. No, for Guha, the failure of the Indian Left to celebrate Indian heroes is the primary reason for the rise of jingoism in our times. This not only betrays an ethnocentricism not dissimilar to the European-style nationalism he criticises, it also echoes the critique made of the Left by those he would term jingoistic.

Perhaps, the Left’s association with the idea of being citizens of the world, rather than of a particular nation, leads Guha to the surprising position that “global citizenship is a mirage; or a cop-out,” and to condemn those who “accord themselves the fanciful and fraudulent title of ‘citizen of the world’.” Really? Is there another way to deal with the planetary environmental crisis outside of seeing ourselves as not bounded by interests of nation-states? This, coming from someone who is an environmental historian, who has written global histories of environmentalism, leaves me frankly flabbergasted. This is not just nationalism, but tantamount to a narrow statism.

And, what of Guha’s well-placed barb about the Indian Left only celebrating dead, white, foreign, men? It was good to see Guha embracing gender as a category of historical analysis, not one he has often employed, whether for understanding politics or cricket. We would be better served if that ran more consistently across the essay, rather than as a way to bash the Left. Gandhi and Tagore are wonderful counterpoints to the current wave of hyper-masculine jingoism. But Guha doesn’t point to Gandhi’s very different imaginings of masculinity or Tagore’s critique of existing gender inequalities as enabling alternative imaginings of India. In fact, other than a passing reference to Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay’s shame, no women other than Indira Gandhi figures in Guha’s essay. There are, on the other hand, lots of savarna men, most of whom are dead.

(The writer is professor of South Asian history at Northern Arizona University. He teaches a course on ‘Contemporary India’ using Guha’s India After Gandhi as the primary text.)